Our ancestors might have started walking on two feet in order to carry food more efficiently suggests new research in the journal Current Biology.

Bipedalism (walking on two feet) is one of the key features that distinguishes us from chimpanzees and gorillas, our closest relatives, but it is also an adaptation that radically changed our evolution when it released our ancestors’ hands to all kind of jobs.

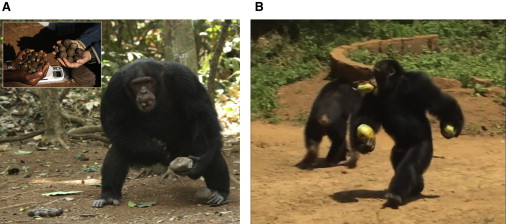

Despite its importance, the reason why the behavior first appeared remains a mystery. But now a study by researchers from Portugal, the UK and Japan, using wild chimpanzees as a proxy model for early hominids, discovered that limited availability of highly desired foods turns the animals bipedal in order to be able to carry more items quicker. Since the circumstances where bipedalism occurs among chimpanzees probably parallel the challenges faced by first hominids, the results suggest that a need to collect and carry food was crucial in the evolution of the upright posture among hominids.

Walking on two feet was a dramatic step in the transition from ape to man. Releasing the hands to make tools and hold weapons or infants led to new ways of feeding and living, as well as the challenges that contributed to the human lineage’s bigger brain. The first signs of bipedalism coincide with a time of major climate changes that reduced forested areas around 5 millions of years ago, and with the first hominids. In fact, Australopithecus 3.6 millions years ago already had physiological changes linked to an upright posture, such as spinal adaptations for vertical pregnancies in females and modified bones in the feet and legs.

But even if environmental changes are linked to the appearance of bipedality among hominids the specific issues/selective pressures that trigger it remain a mystery.

To test one of the main theories on the subject - which proposes that walking upright appeared from a need to free the arms to carry food - researchers Susana Carvalho, Dona Biro and colleagues from the University of Coimbra in Portugal and Oxford and Cambridge Universities in the UK in the study now published studied wild chimpanzees from the forest of Bossou, in Guinea as a proxy model for early hominids. Not only chimpanzees are often bipedal, but those in Bossou, similar to early hominids,are facing an increasingly deforested habitat with highly variable ecological conditions.

To start the researchers tested what would happen when a new nut, more appealing than those that the animals normally had access to, was introduced into their environment comparing three different situations – when the new nut was introduced in high quantities becoming the most common resource, when it was introduced in small amounts and, as control,when it was not present in the environment.

Observing more than 700 food transports Carvalho, Biro and colleagues found that when high quantities of the new nut were introduced chimpanzees not only stopped collecting other nuts but also did three times more food transports (presumably to collect as many new nuts as quickly as possible) showing that the new resource was particularly high-valued.

Images and video courtesy of the journal "Current Biology"

Even more interesting, in the presence of the new nut, food transports were five times more frequently bipedal probably because this allowed chimpanzees to carry twice as many items than when walking on all four limbs.

These results reveal how upright locomotion among chimpanzees can appear from a need to improve food carrying efficiency when resources are scarce or unpredictable, suggesting that the same might have occurred among the early hominids.

To further confirm this possibility Carvalho and Biro next investigated another situation where access to high-valued food was unpredictable - when chimpanzees raided human plantations. Again more than a third of the transports were bipedal with the animals using both their mouth and hands in order to carry many more items.

These are particularly interesting results because bipedality among chimpanzees is usually postural, so not for locomotion, and used to have access to fruit in short trees, not to carry items. The foraging behavior of the Bossou’s chimpanzees - who live in an area where forest has been reduced and replaced by patches of other vegetations or even human plantations – give us with clues on what might have happened during hominid evolution when the ecological conditions were also changing rapidly. If the environment of early hominids also had high value unpredictable resources(maybe as result of the changing climate of the time), then it would have been advantageous to turn bipedal as this allowed individuals to carry and collect more resources quicker increasing their survival chances. And if bipedalism was used often, with time the anatomic changes that facilitated an upright posturewould have been selected and incorporated into the hominids’ populations.

In conclusion, the work now published supports the theory that hominids started to walk upright to be more efficient when carrying food, which could have become scarcer and more unpredictable with the changes in climate (and vegetation) that occurred at the time of the first hominids. Standing upright, by allowing them to carry and collect high-value resources quicker, improved survival chances.

The results also support the idea that highly variable environments (more than specific habitats) were behind important adaptive evolutionary steps in the history of humans.

Citation: "Chimpanzee carrying behaviour and the origins of human bipedality”, Current Biology,Volume 22, Issue 6, R180-R181, 20 March 2012 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.052

Comments