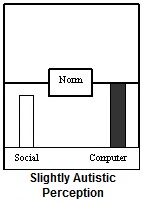

Enter the concept of slight autism. We can define slight autism as a state of autistic perception that is noticeably but not diagnosably autistic. Here is how we can begin to explain it and understand it.

There are at least three kinds of perception – not just one as assumed in psychology all along – and they are qualitatively distinct. There is social thinking and there is computer thinking. There is also a third kind, which is creative thinking, but for the time being we can assume it exists inside the first two – you can be socially creative in your thinking and computationally or logically creative in your computer thinking.

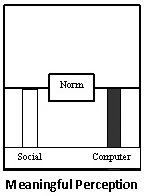

So, imagine everyone has average and normal amounts of social thinking and computer thinking. The social thinking looks around upon entering a social event and decides what is going on here. On the basis of the social hypothesis for what is going on here, the computer thinking then computes the behavior appropriate to the situation. This is a neurotypical person with average amounts of social and computer thinking.

So, imagine everyone has average and normal amounts of social thinking and computer thinking. The social thinking looks around upon entering a social event and decides what is going on here. On the basis of the social hypothesis for what is going on here, the computer thinking then computes the behavior appropriate to the situation. This is a neurotypical person with average amounts of social and computer thinking.

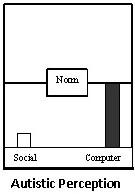

Next, imagine a person who has decidedly more computer thinking than social thinking. The greater the disparity between the social and computer thinking, the more likely that person is to be diagnosed as autistic.

Human perception, including autism and everything else, cannot be understood by assuming that perception is one monolithic thing. There are different types of perception and the varying ratios of one to the other allow us to qualify normative perception, autistic perception … and almost any human state of mind.

* * * * *

This is a simple model of perception in social psychology that posits an analogue between the three modes of logical inference we have in philosophy and science, and our everyday mental experience.

In the philosophy of science, we say science is based on three modes of logical inference: deduction, induction, abduction. In social psychology, we can say that philosophy and science got these from our mind, because we do these every day all day long. In other words, philosophy and science and the three modes of logical inference, are just formalizations of our everyday experience in the informal logic of perception. We already think quite deductively, and inductively, and abductively – how else could we have made up science and philosophy?

Deduction is the logic of math and computers, and it infers the same answers every time – 2+2 = 4 - again and again, over and over and over again, and it will never change. That is the power of deductive logic.

Induction is the logic of research and experiments, and it explores the world through systematic trial and error. It seeks and finds evidence in support of hypotheses, and yields conclusions and ideas that seem to work, but the results overall are never guaranteed.

Abduction is the logic of hypothesis formation, creativity, and evolution. It was Peirce’s bid to capture Darwinian logic in philosophy. It yields creative solutions for problem situations. Abduction is logical because the solutions it yields must be plausible and ultimately they will be verified sometimes, and then become the stuff of everyday deductions and inductions. An abduction is an idea thought for the first time.

So, if we have these kinds of logical inferencing wired into our brains, how might these organize perception? Here is a very good model: we have inductive inferencing and it allows us to wonder What is going on here? as we enter a social situation, and then to begin to look for answers to that simple question.

We have deductive inferencing and it allows us to take the answer to that question What is going on here? and to use it as a hypothetical premise for action. From that premise, the mind deductively computes the appropriate behavior for the social situation.

When we are faced with a problem to solve, a decision to make, or a novel situation, our minds are capable of doing abduction, which is a reorganization of existing experience, a reorganization of existing deductions and inductions, to come up with a brand new idea that explains the new situation. Let’s keep things simple, assume for now that the abductive can be inside the deductive or inductive, we can be creative either way.

Here is the punchline: The hallowed state of normalcy might be assumed to be depicted by a person having equal, and average, levels of inductive social inferencing, and deductive computer inferencing. Not a big surprise there.

But … what if a person had more deductive inferencing wired into their brains than inductive inferencing? Is it possible that the more deductive inferencing a person has naturally wired into their brains, and by comparison, the less inductive inferencing a person has wired into their brains, the more likely they are going to be diagnosed autistic?

The answer is yes, and that brings us to the final point as well as the answer to the original question. We can imagine a person having more deductive inferencing wired into their brains than inductive inferencing. We can also imagine that this person does not have enough of a difference between their deductive and inductive inferencing to allow them to appear as diagnosably autistic. However, the fact that they do have more deductive inferencing thinking than inductive inferencing wired in would mean that such a person would be predisposed to having certain peaks of experience that are decidedly autistic ... but not enough to be diagnosed.

A person who is slightly autistic might be able to present as socially normal when required to do so, but they might have a decided preference for being alone. They might have presented as normal or above average in school, but things that are easy and simple for most people might be challenging for them, and things that are impossible for most people might come easily to them. They might have trouble doing things by the book, but they will also be oddly ritualistic in their own way. These are all variations on the theme of having trouble with social life. They might present as normal for the most part, yet they might also have odd obsessions, for example, over a collection that is special to them but not particularly special to anyone else.

In the end, the singular hallmark of autistic perception and behavior is an obsessive predilection for ritualistic, repetitive, persevering behavior. The same way 2+2=4, every time, the same way, over and over again, Rainman had to watch Jeopardy at the same time every day on TV … or else the world as he knew it would come to an end – it was as if he had just been informed that 2+2 now equals 5.

By the way, if this is no fantasy, and if it is part of our reality, then we all have three kinds of thinking wired into our brains. Of course, it's not formal logic, but we do have an informal inductive inferencing, we do have an informal deductive inferencing, and we do have informal abductive inferencing abilities. And that means the fundamentally deductive mechanics of autistic perception are actually alive and well inside each and every one of us – it is just a question of how much.

~The End~

Comments