Reports that honey bees are dying in unusually high numbers has concerned many scientists, farmers and beekeepers, and gripped the public. There have been thousands of stories ricocheting across the web, citing one study or another as the definitive explanation for a mystery that most mainstream experts say is complex and not easily reducible to the kind of simplistic narrative that appeals to advocacy groups.

This is part one of a two-part series that will examine this phenomenon: how complex science is reduced to ideology, how scientists and journalists often facilitate that--and its problematic impact on public policy, the environment and in this case the wondrous honey bee.

Read Part II HERE.

This series—Bee Deaths Mystery Solved—specifically examines two controversial studies, both authored by the same researcher, that have become the linchpin for those who argue that bees and potentially the planet are facing a Beemageddon. It addresses:

- Who is Chensheng Lu, the nutritionist who has become the face of the movement claiming that Big Ag is threatening bees, humans and our food supply?

- What are neonicotinoids, the supposed time bomb at the center of the controversy?

- What role have journalists played in mis-reporting the bee death story?

- Do prominent entomologists and beekeepers endorse Lu's belief that the world faces a "bee crisis" as Lu’s research, held up by activists as seminal and groundbreaking, contends?

- Will—or should—'neonics' be banned as a precautionary measure?

Chensheng (Alex) Lu, Associate Professor of Environmental Exposure Biology, Harvard School of Public Health. Link: Harvard

Chensheng Lu was in his element Wednesday at a speech at Harvard Law School. The School of Public Health professor was lecturing on his favorite subject--his only subject these days, as it has become his obsession. He is convinced, unequivocally, that a popular pesticide hailed by many scientists as a far less toxic replacement for farm chemicals proven to be far more dangerous to humans and the environment, is actually a killer in its own right.

“We demonstrated that neonicotinoids are highly likely to be responsible for triggering Colony Collapse Disorder in bee hives,” claimed Lu. The future of our food system and public health, he said, hangs in the balance.

Lu is the Dr. Doom of bees. According to the nutritionist--but not clear to most other experts in the field-- colony collapse disorder (CCD), which first emerged in 2006, can be directly linked to "neonics", as the now controversial class of pesticides is often called, and also to genetically modified crops. Phased in during the 1990s, neonics are most often used by farmers to control unwanted crop pests. They are coated on seeds, which then produce plants that systemically fight pests.

To many environmental activists, the pesticide does more harm than good, and they've found their champion in Chensheng Lu. It's been a busy fall for the professor, jetting back and forth between Boston and Washington, with forays around the United States to talk to adoring audiences. He presents himself as the defender of bees, and this fiery message has transformed a once obscure academic into a global "green" rock star, feted at events like yesterday's lunch talk at Harvard..

The sudden abandoning of hives by honey bees known as Colony Collapse Disorder has emerged as one of the hottest science mysteries in recent years. Lu has authored two extremely controversial papers on CCD: one in 2012 and a second published this past spring. He and his two beekeeper colleagues - there were no entomologists on his tiny research team - contend that neonicotinoids present a mortal threat to bees. Not only that, Lu claims, neonics endanger humans as well, accelerating Parkinson’s Disease.

Lu reached folk hero status among environmentalists last May when the Harvard School of Public Health launched a promotional campaign touting his latest, controversial research: “Study strengthens link between neonicotinoids and collapse of honey bee colonies,” the press release claimed. Before the study was even circulated, stories in some mainstream publications including Forbes ran the release with only a pretense of a rewrite..

The story exploded on the Internet. Many environmental and tabloid journalists painted an alarmist picture based on Lu's research: “New Harvard Study Proves Why The Bees Are All Disappearing,” “Harvard University scientists have proved that two widely used neonicotinoids harm honeybee colonies,” and “Neonicotinoid Insecticide Impairs Winterization Leading to Bee Colony Collapse: Harvard Study” are three of thousands of blog posts and articles.

Considering the tsunami of stories citing Lu’s study” as “proof” that neonics cause CCD, you might be scratching your head over the slightly tongue-in-cheek headline to this piece. These ‘dangerously toxic chemicals don’t cause mass bee deaths? They may improve bee health?

Although this headline is an overstatement, as you will learn, it may actually be closer to the truth than the tsunami of headlines that show up when you search the web for stories of the mystery of bee deaths.

Behind the headlines

Although public opinion has coalesced around the belief that the bee death mystery is settled, the vast majority of scientists who study bees for a living disagree—vehemently.

How could a “Harvard study” and a sizable slice of the nation’s press get this story so wrong?

The buzz that followed the publication of Lu’s latest study is a classic example of how dicey science can combine with sloppy reporting to create a ‘false narrative’—a storyline with a strong bias that is compelling, but wrong. It’s how simplistic ideas get rooted in the public consciousness. And it's how ideology-driven science threatens to wreak public policy havoc.

Bees are important to our food supply. They help pollinate roughly one-third of crop species in the US, including many fruits, vegetables, nuts and livestock feed such as alfalfa and clover. That's why the mystery of CCD is so troubling.

One of the central problems with Lu’s central conclusion—and much of the reporting—is that despite the colony problems that erupted in 2006, the global bee population has remained remarkably stable since the widespread adoption of neonics in the late 1990s. The United Nations reports that the number of hives has actually risen over the past 15 years, to more than 80 million colonies, a record, as neonics usage has soared.

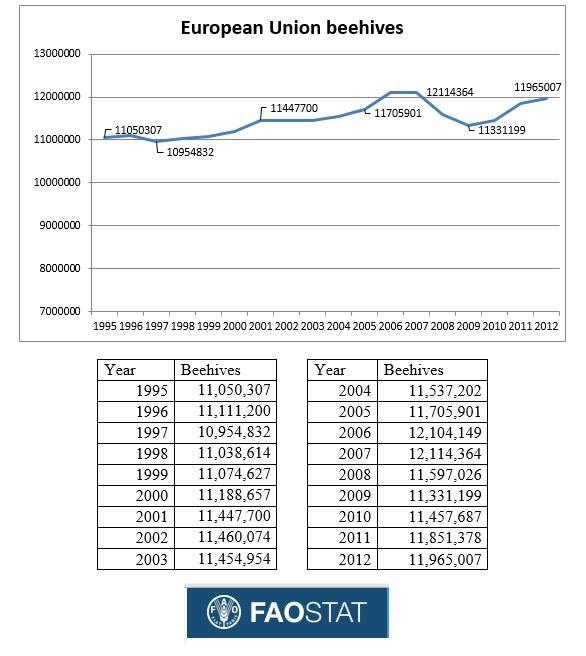

Country by country statistics are even more revealing. Beehives are up over the past two decades in Europe, where advocacy campaigns against neonics prompted the EU to impose a two-year moratorium beginning this year on the use of three neonics.

Last February, the government of Australia, where neonics are used extensively, reaffirmed that “honeybee populations are not in decline despite the increased use of [neonicotinoids] in agriculture and horticulture since the mid-1990s.” Its central finding was just the opposite of what many in the media have reported: The APVMA (Australian equivalent of the EPA) concluded, “[T]he introduction of the neonicotinoids has led to an overall reduction in the risks to the agricultural environment from the application of insecticides.”

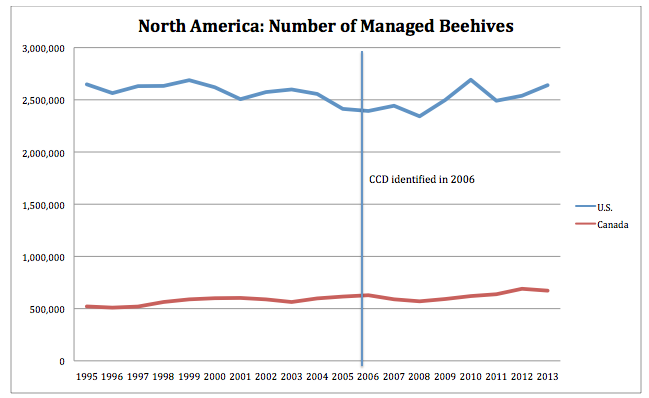

According to statistics Canada honey bee colonies have increased from 521,000 in 1995 to 672,000 in 2013, a record. North American managed beehive numbers have held stable over the last two decades.

Sources: USDA and Statistics Canada

So how did the narrative that the world faces a beepocalypse become settled wisdom? The media have widely conflated two parallel but different phenomena: Bee deaths related to CCD and bees dying from other causes.

Bee health took a sharp hit in the 1980s and has been struggling during the winter months for decades coinciding with the global spread of the parasitical Varroa destructor mite and the sub-lethal effects of miticides used to control the parasite. But these overwinter losses, while troubling, haven’t translated into declines in the overall bee population because bees reproduce rapidly in warmer months.

The bee health issue erupted into the public consciousness in 2006, when bee die-offs mysteriously spiked—in California to as high as 80%.

GMOs and Cell Phones Did It?

The event was dubbed CCD by a team of entomologists because of the unique characteristics of the deaths: the unusual abandonment of hives by the oldest bees leaving behind larvae, the queen and food stores.

Advocacy groups originally pointed to cell phones and genetically modified crops as the likely culprits, and some fringe organizations, like the Organic Consumers Association, still do. But CCD gradually subsided.

Dennis van Engelsdorp, a University of Maryland entomologist who was part of the research team that named CCD, has written to me that there has not been a single field CCD incident in the last three years, except cases linked to the Nosema fungus. Confusing the picture, overwinter bee deaths also increased in the years after the CCD scare, reaching 30% or more in the US and in some European countries. Confounding doomsayers, losses plummeted to 21.9% over the winter of 2011-2012, jumped again during the following year’s frigid weather, then settled back into the low 20s.

In some states, like North Dakota, which is the largest honey producer in the US, the number of bee colonies has hit an all-time high.

The recent trend in Europe is also encouraging. In April, the EU released a report called Epilobee that surveyed bee health in 2012-2013. Seventy-five percent of bees suffered overwinter losses of 15% or less, a level considered well within the acceptable range in the US. Only countries in Europe’s far north, home to 5% of the bee population, and which suffered through a bitter winter, experienced losses of more than 20%.

In short, most entomologists scoff at media references of a beemageddon.

But that’s exactly what Lu claims.

Hyping The “Harvard” Studies

Mother Jones, in its coverage led by food reporter Tom Philpott, has been particularly relentless in its promotion of Lu’s controversial views. It’s run more than a dozen articles about the alleged mortal threat posed by neonics. Upon the release of Lu’s most recent study, Philpott titled his article, “Did Scientists Just Solve the Bee Collapse Mystery?”

There were no “scientists” behind the Lu study, of course—only Lu himself. But rather than seeking out views of established experts in the field, he had Lu and only Lu answer the question he posed.

“[C]oming on the heels of a similar [study] he published in 2012, the CCD mystery has been solved,” he wrote. Philpott now unqualifiedly refers to neonics as “bee killer chemicals.”

Who is Chensheng (Alex) Lu, the Dr. Doom of honey bees? He is an environmental researcher with the Harvard School of Public Health with no formal training in entomology. His two bee papers are “Harvard studies” only in the sense that the only scientist who conducted the studies has a Harvard faculty appointment; his co-authors are local beekeepers. Both studies appeared in one of the most obscure science journals in the world, a marginal Italian journal.

Lu emerged out of academic obscurity two years ago with the publication of his first study on bee deaths. He promoted a simple explanation, the kind that energizes activists: A new class of pesticides, promoted by large chemical companies as a safer alternative to older chemicals, was a hidden killer.

“I kind of ask myself," Lu told Wired in 2012. “Is this the repeat of Silent Spring? What else do we need to prove that it’s the pesticides causing Colony Collapse Disorder?”

The second coming of Silent Spring? Almost from the day his first study was published, Lu was making grandiose claims. By his own admission, he is the definition of an activist scientist. He is on the board of The Organic Center, an arm of the multi-million dollar Organic Trade Association, a lobby group with strong financial interest in disparaging conventional agriculture, synthetic pesticides and neonics in particular—a conflict of interest that Lu never acknowledges and to my knowledge no other journalist has reported.

Earlier this month, OTA announced it had hired Lu to tout the benefits of organics, including promoting the dangers of neonics.

Many of the world’s top scientists have challenged his research. vanEngelsdorp called Lu’s first study “an embarrassment” while Scott Black, executive director of the bee-hugging Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, characterized it as fatally flawed, both in its design and conclusions.

University of Illinois entomologist May Berenbaum, who chaired the National Academy of Sciences 2007 National Research council study on the Status of Pollinators in North America? called it “effectively worthless” to serious researchers. “The experimental design and statistical analysis are just not reliable,” she said.

Beekeepers have been skeptical as well. Lu’s findings contradicted what they witnessed in the fields. If neonics were a mystery killer, then not using them should translate into healthier bee stocks; but that’s not what has happened.

“In places where neonicotinoid pesticides have been banned, such as France and Italy, there’s no evidence that honeybee populations have rebounded,” noted Hannah Nordhaus, beekeeper and author of the bestseller The Beekeepers’ Lament.

Lu has been defiant since the stinging expert rejection of his first paper. He suspects the fingerprints of a Big Ag conspiracy of chemical companies, USDA and entomologists who he believes are ignoring the dangers to bees. Those are damning charges if true, but Lu had yet to present any evidence to back them up—until the publication of his newest paper last May.

Lu monitored 18 hives, a small number for such a complex study, comparing two different pesticides in different locations. He fed bees high fructose corn syrup laced with two neonics, imidacloprid and clothianidin, for 13 weeks. It was an odd choice because bees in fields usually only feed for as few as two weeks. Six of the 12 colonies fed neonics eventually ended up showing substantial deaths over the winter, as did one of the six control colonies.

According to Lu and his beekeeper co-authors, this proved that neonics cause CCD.

To seasoned observers of the bee controversy, the “new” study looked like more of the same. “Lu’s sample sizes are astonishingly small,” May Berenbaum told me, ticking off a litany of problems. ”He never tested for the presence of pathogens, so his conclusions dismissing other likely causes don’t follow from his data. The whole study just doesn’t hold together. And I’m not being a fusspot here. It’s unfortunate this was presented as a Harvard paper because it gives this credibility that it doesn’t deserve.”

Twitter lit up with critical comments, starting with Nordhaus.

This new study linking neonics and bees is from the author of earlier widely discredited study Harvard study. http://t.co/4rjMNg4Dyp

— Hannah Nordhaus (@hannahnordhaus) May 12, 2014Other critical posts followed, including by Brian Ames, a prominent apple grower, artisanal honeymaker and beekeeper:

@eatsustainable @FoodNavigator unethical Harvard study on bees uses unrealistic dose of neonics&misleads public http://t.co/USwdSv7WdW

— Brian Ames (@amesfarmhoney) May 15, 2014Even rudimentary digging by reporters would have turned up the revealing fact, unreported by the adulatory environmental press, that first study was rejected by Nature, as Lu himself has acknowledged, before ending up in the Bulletin of Insectology, a marginal “pay for play” publication that is known to publish research often rejected by mainstream peer-reviewed journals.

(The Bulletin of Insectology has an “impact factor” (IF) of 0.375, which means that the average paper from that journal is cited by another journal approximately once every three years; in contrast, Nature, which rejected Lu’s first paper, has an IF of 51).

The second study faced the same fate. Unable to get his work published by credible journals, Lu returned to the same publication that put out his first piece—perhaps the only journal in the world that would publish it.

"Anyone at this point in time who wishes to make a contribution to the study of potential effects of neonicotinoids on honey bees—or any other aspect of honey bee health—and publishes this data in the extremely obscure journal Bulletin of Insectology is very hard to take seriously,” Colorado State University entomologist Whitney Cranshaw emailed me.

PART II: Neonics and bees: What does the future hold?

Jon Entine, executive director of the Genetic Literacy Project, is a senior fellow at the World Food Center at the University of California-Davis and the Center for Health&Risk Communication at George Mason University. Follow Jon on Twitter @JonEntine

Comments