Three reasons why government can look less efficient than it really is:

1. Cherry-picking in privatization. Let’s suppose we could rank government agencies or services in descending order of productivity: 1, 2, 3, and so on, with agency 1 being the most efficient and productive. As a reality check, let’s note that such a ranking is indeed possible, in a rough way.

For the sake of a simple example, though, imagine a government with only seven services. Taking “efficiency” to mean providing a needed service[1] using the least amount of dollars, and indexing the most efficient of the seven to an arbitrary 100% efficiency, a list might look like this:

Service #1 100% efficient.

Service #2 92% efficient.

Service #3 87% efficient.

Service #4 75% efficient.

Service #5 63% efficient.

Service #6 59% efficient.

Service #7 44% efficient.

The average efficiency of this set of services is 74%.

Suppose further that a critic of government says, “Government is inefficient! Its functions should be privatized! The private sector can operate it more productively!” He succeeds in getting several put up for bid. Which government services will our critic try to acquire? The most productive one that’s up for grabs, naturally. He cherry-picks Service #1, taking it out of the government sector and into private management.

As astute policy wonks, we notice the average efficiency of the remaining six government services is 70%. Privatization has lowered the overall efficiency of government. This is not lost on Mr. Critic, either, and he bends it to his purposes, conveniently glossing over the fact that he caused it. “See?” he crows, “Government inefficiency is getting worse by the year! Something needs to be done, and that something is more privatization!”

You can see how the story will play out. Whittling away, downward spiral, choose your metaphor. It’s a dirty game.

This is a good moment to remind you that I’m not here today to trash privatization per se, but rather to talk about the image of government. If we could privatize with a greater dose of good intent[2] and a lot less hypocrisy, I’d have no problem with privatization.

2. The Baumol Paradox. Economist William Baumol identified a financial reality that has come to be known as “Baumol’s Cost Disease.” It has drawn much press attention lately, though university administrators have known for years that the Baumol cost disease is “the central problem in educational finance” (Kleiman 2011). Heilbrun (2003) explains:

IT and e-government have developed rapidly in recent times, but they are not central to the production and enforcement of laws; they are only facilitators, and so they differ fundamentally from the capital equipment used in manufacturing....increases in productivity are most readily achieved in industries that use of a lot of machinery and equipment. In such industries output per worker can be increased either by using more machinery or by investing in new... technology. As a result, in the typical manufacturing industry the amount of labour time needed to produce a physical unit of output declines dramatically decade after decade. [Public and service agencies are] at the other end of the spectrum.Machinery, equipment and technology play only a small role in their production process and, in any case, change very little over time.

Baumol colorfully remarked, “It takes four musicians as much playing time to perform a Beethoven string quartet today as it did in 1800.” Firing one of the four musicians, or amplifying the music electronically so as to play to a larger hall, or forcing the musicians to play faster, would increase nominal productivity but would seriously degrade the quality of the listener’s experience.

Heilbrun continues with the performing arts analogy:

Costs in the live performing arts will rise relative to costs in the economy as a whole because wage increases in the arts have to keep up with those in the general economy even though productivity improvements in the arts lag behind.... As a result, cost per unit of output in the live performing arts is fated to rise continuously relative to costs in the economy as a whole.

It is not just theory. Baumol and his colleagues verified it on historical data sets for various service-intensive industries in several countries. He found, for instance, that the average cast size of Broadway shows has decreased more or less steadily since 1947. This is the producers’ attempt to limit the rise of labor cost per ticket sold. However, there is a limit: One cannot perform Hamlet with half the cast members of Shakespeare’s original.

Indeed, cost per unit of output in all service enterprises, including government, are “fated to rise continuously relative to costs in the economy as a whole.” This is the heart of the Baumol cost disease.

Though you might imagine benefits from making government do what they do faster, louder, and with fewer people, you can also imagine the limits to this “solution.” As manufacturing occurs mostly in the private sector and government mostly consists of services, government productivity will lag behind that of the general economy no matter which party is in power.

3. Hyper-accountability. Open-records acts, open-meeting laws, public fora, etc., are a result of taxpayers’ correct wish for transparency in government. It’s hard to say demands for transparency could in any way be called “extreme.” The more transparency the better, save that we understand the CIA must do some secret stuff.

The consequences, though, can seem extreme. An example: One public agency takes no less than six days to clear and issue a single piece of correspondence – a simple letter! – because experts in several regulatory areas must put in their 2¢ to ensure the letter meets all rules for open and fair treatment of constituents.

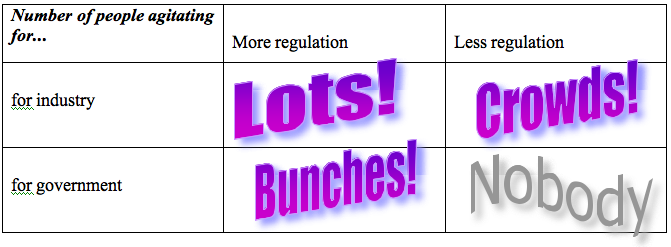

Painted in that light, such hyper-accountability looks ridiculous. Industry is not the only sector that can be called over-regulated! And citizens need as much transparency from industry as we do from government. The difference is the many lobbyists (and legislators) paid big bucks to decry industry regulation. No one has a motive to crusade for fewer restrictions on government.

As a result, industry gets apparent efficiencies. I stress “apparent” because many are gained only at the expense of needed transparency. Government then appears to suffer in efficiency comparisons.

I am not denying that there are real inefficiencies in government, some quite egregious. My point is that, as in so many other areas, appearances deceive. Things are not always as they seem, and in this case many apparent government inefficiencies are not matters of reality or of fault.

[1] that people would use and pay for if government did not provide it.

[2] i.e., not as a cover for putting commissions into the pockets of brokers, as would happen under social security privatization, or for raising prices at will and doing away with consumer protections, all of which leave taxpayers effectively paying more and getting less than they did before privatization.

Comments