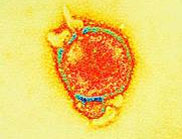

There is no cure for the HeV virus, and it usually kills people and horses. It is hoped that an HeV vaccine currently being developed by the CSIRO will be available in 2013 because of the seven people known to have ever contracted HeV since 1994, four have died from the virus and approximately 70% of horses that contract the virus have also died and even those that survive are usually then euthanised as part of a Government health policy.

As a horse owner living in a district where 2 horses have died in nearby Lismore and Mullumbimby in the last 2 weeks and many more are quarantined, I decided that it was time to do some research into what we know about this deadly HeV virus, how much of a real risk it is to me and my horses and now also my dogs, how I can minimise that risk and what is the likely outcome if one or more of my horses should become infected. I was stunned to learn that not a lot is known about HeV and more scientific research is desperately needed.

As a horse owner living in a district where 2 horses have died in nearby Lismore and Mullumbimby in the last 2 weeks and many more are quarantined, I decided that it was time to do some research into what we know about this deadly HeV virus, how much of a real risk it is to me and my horses and now also my dogs, how I can minimise that risk and what is the likely outcome if one or more of my horses should become infected. I was stunned to learn that not a lot is known about HeV and more scientific research is desperately needed.HeV History

The Hendra virus was discovered in September 1994 when it caused the deaths of 13 horses, and a trainer at a horse training complex in Hendra, a suburb of Brisbane in Queensland, Australia. The first case was a mare stabled with 19 other horses who died two days after falling ill, the 19 other horses then all became ill and 13 died. The remaining 6 animals were subsequently euthanised as a way of preventing relapsing infection and possible further transmission. The trainer, Victor Rail, and a stable hand who both nursed the first sick mare also became ill within one week of her death with an influenza-like illness. The stable hand recovered but Mr Rail died of respiratory and renal failure.

There was also a second outbreak in August 1994, which chronologically preceded the Hendra outbreak in Mackay 1,000 km north of Brisbane and which resulted in the deaths of 2 more horses and their owner. The owner, Mark Preston had assisted in the post mortem of the horses and was admitted to hospital 3 weeks later, suffering from meningitis. Mr Preston recovered, but 14 months later developed neurologic symptoms and then died. This outbreak was diagnosed retrospectively by a post mortem showing the presence of Hendra virus in his brain.

Transmission from bats

Hendra virus is a zoonotic disease, which means it can transfer from animals to people, the word is derived from the Greek words zoon "animal" and nosos "ailment". HeV has been found to be carried by the hundreds of thousands of Pteropid fruit bats or ‘flying foxes’ that inhabit Australia, Papua New Guinea, and surrounding islands. So far, clinical disease due to HeV infection has only been recognised in Australia.

Fruit bats are a natural host and appear to be relatively unaffected by the virus though their rate of virus emission tested in their droppings fluctuates roughly between 9% and 30% seasonally and this virus emission rate appears to increase when the bats are under more stress to find food during the winter months between May and September. At this time they are also giving birth and lactating when there is often a corresponding peak of horses being infected by HeV occurring around July and August. It is thought likely that this year, record-breaking rain over summer may have also left flying foxes undernourished and stressed, with weakened immune systems and a higher amount of Hendra virus in their bodies.

Fruit bats are a natural host and appear to be relatively unaffected by the virus though their rate of virus emission tested in their droppings fluctuates roughly between 9% and 30% seasonally and this virus emission rate appears to increase when the bats are under more stress to find food during the winter months between May and September. At this time they are also giving birth and lactating when there is often a corresponding peak of horses being infected by HeV occurring around July and August. It is thought likely that this year, record-breaking rain over summer may have also left flying foxes undernourished and stressed, with weakened immune systems and a higher amount of Hendra virus in their bodies.On Monday, a horse vet at Agnes Banks Equine Clinic in the Hawkesbury, Derek Major said that “Hendra virus is a death sentence for a horse...there are bats who have been exposed to this virus flying over our heads now. There is a much more widespread geographical distribution of Hendra this year than previously, there are more cases everywhere.” He believes this is due in part to the bats’ need to forage further afield because of habitat destruction and loss. According to the Wilderness Society every few minutes in New South Wales an area of bushland the size of three soccer pitches is being cleared, removing crucial trees and habitats for Australian wildlife and causing more stress for these bats or ‘flying foxes’.

Although the hendra virus occurs naturally in flying foxes; governments and experts stress that these animals should not be targeted for culling. Flying foxes are protected species and are critical to our environment as they pollinate what is left of our native trees and spread seeds. Without flying foxes, we wouldn’t have any eucalypt forests, rainforests and melaleucas. Any unauthorised attempts to disturb flying fox colonies are not only illegal but also ineffective for a number of reasons:-

• Flying foxes are an important part of our natural environment.

• Flying foxes are widespread in Australia and are highly mobile.

• There are more effective steps people can take to reduce the risk of Hendra virus infection in horses and people.

• Attempts to cull flying foxes could make the problem worse by further stressing them and causing increased excretion of Hendra virus. For more information about flying foxes, contact the Department of Environment and Resource Management on 1300 130 372 or visit www.derm.qld.gov.au

Flying foxes and trees

Flying foxes are attracted to a broad range of flowering and fruiting trees and vegetation as a food source. Some examples of the trees and vegetation on properties where Hendra virus in horses has occurred include:-

• a range of fig trees (including the Moreton Bay fig tree)

• melaleucas (including paperbarks)

• eucalypts

• wattles

• passionfruit vines.

Other trees that may attract flying foxes include flowering or fruiting trees with soft fruits and stone fruits (e.g. mangoes, pawpaws), palms, lilly-pillies and grevilleas. This is not a comprehensive list of trees that are attractive to flying foxes as this will vary from one geographical area to another. Many horse owners are now removing these trees from their properties for obvious reasons, which will of course further stress the bat populations.

Transmission of HeV by other animals

It is possible that other animals such as possums for example could also be Hendra virus hosts and this is currently being researched by scientists though initial tests have shown to be negative further research is required.The Hendra virus is one of five new zoonotic viruses discovered in Pteropid fruit bats since 1994, the others being the Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV), the Nipah virus, the Menangle virus and the Melaka virus. Of these, ABLV which is closely related to the rabies virus is the only virus known to be transmissible to humans directly from bats without an intermediate host and so far there have only been two recorded cases both on the East coast of Australia where people were either scratched or bitten by fruit bats carrying ABLV.

Testing for HeV

Testing for HeVAny sick animals and/or animals and people known to have come into contact with infected horses on Australia’s east coast are tested for HeV either by Biosecurity in Queensland (QLD) or by the Department of Primary Industries in New South Wales (NSW DPI). They advise that anyone who is worried that their horse could have Hendra virus should keep everyone away from the horse and call their private veterinarian immediately, who will notify the relevant authorities, as HeV is a notifiable disease. If their vet is unavailable and the illness is progressing rapidly, they should call the Emergency Animal Disease Watch Hotline on 1800 675 888. If an animal tests positive then any animals who have come into contact with the infected animal will then be placed under observation and quarantine while the affected farms, paddocks and premises are cordoned off.

The most recent tests on cats and dogs on 11 affected properties currently under quarantine in Queensland have turned up only one new positive result but 2 results are still outstanding. However, for the first time a family pet Kelpie dog called Dusty has tested positive on an infected property at Mt Alford, south of Brisbane.

Dusty, the family kelpie diagnosed with the Hendra virus. Photo: Channel Ten

Dusty, the family kelpie diagnosed with the Hendra virus. Photo: Channel TenAccording to Queensland chief vet Dr Rick Symons "We knew that a dog could be infected but we've never seen a natural transmission, what we are seeing here is an evolving disease and an evolving virus, and there are changes as the virus evolves and the exposure changes." The dog returned two negative results for the virus, but a different type of test conducted at the Australian Animal Health Laboratory in Victoria had confirmed the presence of hendra antibodies.This means that at some point the dog has been exposed to the virus but to their knowledge has shown no signs of illness.

Reports indicate that this Australian Kelpie, a much loved family companion, will sadly probably have to be euthanised in line with government policy to protect public health. At present he is still alive and isolated while authorities are awaiting the results of more tests before making the final decision about Dusty’s fate. Biosecurity Queensland suggest the dog most likely was exposed to HeV through one of the sick horses on the same property but this is by no means certain, like everything else about HeV.

This case has raised many questions for biosecurity and health officials and researchers. Authorities are now recommending that people keep dogs and cats away from sick horses to reduce the risk of such an infection. The remaining horses and dogs on this property are still being monitored daily and show no signs of illness.

Urgent need for more scientific research

The scientific information available on the Hendra virus is still incomplete and research urgently needs to discover much more about this disease. On July 27th July 2011 it was announced that the Queensland and NSW governments will increase Hendra virus research funding by $6 million over the next three years. In scientific experiments by the CSIRO and the Department of Employment, Economic Development and Innovation (DEEDI) Biosecurity Queensland cats, guinea pigs, ferrets and pigs have been infected experimentally with Hendra virus but the virus has not been known to occur naturally in these animals.

HeV can cause significant morbidity and mortality in humans and domestic animals and is widely distributed in Pteropus fruit bat hosts, yet little is known about its ecology and epidemiology or how it is transmitted within Pteropus flying fox and bat populations or even from Pteropus hosts to domestic animals. The bats nomadic lifestyle and complex social structure and the sporadic nature of bat-borne disease outbreaks, has limited large-scale study on these pathogens and limited progress in understanding their dynamics within bats.

Flying fox - photo Jonathon Carroll

Recent studies earlier this year have shown that almost one third of Queensland's bats are now infected with the Hendra virus, more than four times the normal rate, new tests reveal based on research on infected bat populations.

Recent studies earlier this year have shown that almost one third of Queensland's bats are now infected with the Hendra virus, more than four times the normal rate, new tests reveal based on research on infected bat populations.How HeV is transmitted

It is thought that the Hendra virus can be transmitted from flying fox to horse, horse to horse, horse to human and now for the first time this week either from horse to dog or flying fox to dog but probably not the latter. There is no evidence yet of Hendra virus spreading from person to person, from flying fox to human or from dog to human. The exact way that it is transmitted is not yet fully understood but it is thought that horses are infected by somehow ingesting flying fox body fluids and excretions such as their saliva either in water or on half-eaten fruits and flowers, or from their urine, faeces and afterbirth, which drop from bats that are either flying overhead, roosting and/or feeding in trees above horse paddocks and potentially contaminating the horses’ grazing grass, water holes and any feed and water in containers below.

There have been 7 known cases of Hendra virus infection in humans since 1994 and all of these have resulted from close contact with respiratory secretions such as mucus and/or blood from an infected horse. Other people have reported having some contact with infected horses but have remained well, and their blood tests have shown no evidence of Hendra virus infection.

Geographical distribution of outbreaks

As of 24 July 2011, a total of twenty-six events of Hendra virus have occurred, all involving infection of horses. Four of these outbreaks have spread to humans as a result of direct contact with infected horses. On 26 July 2011 a dog living on the Mt Alford property was found to have HeV antibodies, the first time an animal other than a flying fox, horse, or human has tested positive outside an experimental situation.

These HeV events have all been on the east coast of Australia, with the most northern case at Cairns, Queensland and the event furthest south at Macksville, NSW. Until the outbreak at Chinchilla, Queensland in July 2011, all outbreak sites had been within the distribution of at least two of the four mainland flying-foxes (fruit bats); Little red flying-fox, (Pteropus scapulatus), black flying-fox, (Pteropus alecto),grey-headed flying-fox,(Pteropus poliocephalus) and spectacled flying-fox, (Pteropus conspicillatus). Chinchilla is within the range of Little red flying-fox and it is west of the Great Dividing Range. This is the furthest west that the infection has ever been known to occur in horses. The timing of incidents indicates a seasonal pattern of outbreaks, possibly related to the seasonal habits of the grey-headed flying-fox, and the black flying-fox and the spectacled flying-fox birthing.

These HeV events have all been on the east coast of Australia, with the most northern case at Cairns, Queensland and the event furthest south at Macksville, NSW. Until the outbreak at Chinchilla, Queensland in July 2011, all outbreak sites had been within the distribution of at least two of the four mainland flying-foxes (fruit bats); Little red flying-fox, (Pteropus scapulatus), black flying-fox, (Pteropus alecto),grey-headed flying-fox,(Pteropus poliocephalus) and spectacled flying-fox, (Pteropus conspicillatus). Chinchilla is within the range of Little red flying-fox and it is west of the Great Dividing Range. This is the furthest west that the infection has ever been known to occur in horses. The timing of incidents indicates a seasonal pattern of outbreaks, possibly related to the seasonal habits of the grey-headed flying-fox, and the black flying-fox and the spectacled flying-fox birthing. Chronological history of HeV Infections (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hendra_virus)

August 1994, Mackay, Queensland: Death of two horses and one person, Mark Preston.

September 1994, Hendra, Queensland: 20 horses died or were euthanised. Two people infected, with one death, Victor Rail.

January 1999, Trinity Beach, Cairns, Queensland: Death of one horse.

October 2004, Gordonvale, Cairns, Queensland: Death of one horse. A veterinarian involved in autopsy of the horse was infected with Hendra virus, and suffered a mild illness.

December 2004,Townsville, Queensland: Death of one horse.

June 2006, Peachester, Sunshine Coast, Queensland: Death of one horse.

October 2006, Murwillumbah, New South Wales: Death of one horse.

July 2007, Clifton Beach, Queensland: Infection of one horse (euthanized).

July 2008, Redlands, Brisbane, Queensland: Death of five horses; four died from the Henda virus, the remaining animal recovered but was euthanized because of the threat to health. Two veterinary workers from the affected property were infected leading to the death of one, veterinary surgeon Ben Cuneen, on the 20th of August, 2008. The second veterinarian was hospitalized after pricking herself with a needle she had used to euthanize the horse that had recovered. A nurse exposed to the disease while assisting Cuneen in caring for the infected horses was also hospitalized.

July 2008, Cannonvale, Queensland: Death of two horses.

July 2008, Proserpine, Queensland; Death of four horses.

July 2009, Cawarral, Queensland: Death of four horses.Queensland veterinary surgeon Alister Rodgers tested positive after treating the horses.

September 1, 2009 after two weeks in a coma, he became the fourth person to die from exposure to the virus.

September, 2009,Bowen, Queensland. Death of two horses.

May 2010, Tewantin, Queensland: Death of one horse.

June 26, 2011, Kerry (the horse was moved after it became sick to another property at Beaudesert), Queensland: Death of one horse. Eight people tested for infection.

June 30, 2011 Wollongbar, New South Wales: Death of one horse, nine people being monitored for potential exposure. The second horse on the property tested positive to Hendra and was euthanised on 12 July 2011.

June - July 2011 Mt Alford, (near Boonah) Queensland: Death of three horses (all confirmed to have died of Hendra). Six people and eight other horses exposed. The first horse death on this property occurred on 20 June 2011, although it was not until after the second death on 1 July 2011 that samples taken from the first animal were tested. The third horse was euthanised on 4 July 2011. On 26 July 2011 a dog from this property was reported to have tested positive for HeV antibodies. Reports indicate that this Australian Kelpie, a family companion, will be euthanised in line with government policy. Biosecurity Queensland suggest the dog most likely was exposed to HeV though one of the sick horses.

July 3, 2011 Macksville, New South Wales: Death of one horse, 6 people potentially exposed.

July 4, 2011 Park Ridge, Logan City, Queensland: Death of one horse, 2 people potentially exposed.

July 11, 2011 Kuranda, west of Cairns, Queensland: Death of one horse, 4 people potentially exposed, 37 horses potentially exposed.

July 13, 2011 Hervey Bay, Queensland: Death of one horse, one horse being monitored. There is no information about any people who may be monitored for potential exposure.

July 14, 2011 Lismore, NSW: Death of one horse, 1 other horse being monitored.

July 15, 2011 Boondall, Queensland: Death of one horse, 6 other horses being monitored. There is no information about any people who may be monitored for potential exposure.

22 July 2011 Biosecurity Queensland announced that a horse that died in Loganlea, Logan City on 28 June 2011 had tested positive for Hendra antibodies and "extremely low levels of Hendra virus in its blood at the time it was sampled. This, together with the level of antibodies, suggests that the horse may have had a previous Hendra virus infection and had developed some antibodies". The implications of this death have yet to be publicly discussed.

July 22, 2011 Chinchilla, Queensland. One horse has died and four horses being monitored.

July 24, 2011 Mullumbimby, NSW. One horse died and four horses, three cats and two dogs are being monitored. One of the horses is reported to be ill.

Symptoms in horses

Hendra virus can cause a range of symptoms in horses. Usually, there is an acute onset of fever with rapid progression to death associated with either respiratory or neurological signs. Hendra virus should be suspected whenever a horse’s health deteriorates rapidly. However, in some cases the onset of signs is more gradual. One of the two known NSW cases survived four days before being euthanised.

Hendra virus infection should be considered in any sick horse where the cause of illness is unknown and particularly where there is rapid onset of illness, fever, increased heart rate and rapid deterioration associated with either respiratory or nervous signs.

The following signs have all been associated with Hendra virus cases, but not all of these signs will be found in any one infected horse:-

• rapid onset of illness

• increased body temperature/fever

• increased heart rate

• discomfort/weight shifting between legs

• depression

• rapid deterioration with either respiratory and/or nervous signs.

Respiratory signs include:-

• respiratory distress

• increased respiratory rate

• nasal discharge at death—can be initially clear, progressing to stable white froth and/or stable blood-stained froth.

Nervous signs include:-

• wobbly gait

• apparent loss of vision in one or both eyes

• aimless walking in a dazed state

• head tilting and circling

• muscle twitching

• urinary incontinence

• inability to rise.

Symptoms in humans

The few known cases of human Hendra virus infection have shown the following signs:-

• an influenza-like illness (which led to pneumonia in one case) with symptoms such as fever, cough, sore throat, headache and tiredness and/or

• encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) with symptoms such as headache, high fever and drowsiness, which progressed to convulsions and/or coma and death.

Incubation Period

The time from a person’s exposure to a sick horse to the start of illness has been between five and 21 days.

Who to contact about human health concerns

Anyone with human health concerns at any time, should seek medical advice. Contact your general practitioner, local hospital emergency department or local public health unit if you have concerns about possible exposure of people to a horse infected with Hendra virus. For general enquiries about Hendra virus infection in humans, call the Queensland Health Hotline on 13 HEALTH (13 43 25 84). For more information about managing the risk of Hendra virus in the workplace, contact Workplace Health and Safety Queensland on 1300 369 915 or visit www.worksafe.qld.gov.au

The Australian Veterinary Association advises the following :-

12 SIMPLE STEPS TO MINIMISE THE RISK OF HENDRA FOR YOURSELF AND YOUR HORSE.

1. WEAR DISPOSABLE GLOVES. Always have a box of disposable gloves on hand. Wear them if doing anything with a horse that involves contact with horse body fluids. THIS IS IMPORTANT.

2. WEAR Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) IF IN ANY DOUBT. Do not, in any circumstances, approach or attempt to do anything potentially invasive with any suspect horse without adequate PPE. Leave it to the Experts.

3. WASH YOUR HANDS AND EQUIPMENT. A most important factor. Strict personal hygiene is the key component in avoiding infection. Wash hands and equipment and use disinfectant.

4. TPR YOUR HORSE DAILY. Any deviation in the horse’s temperature, heart rate, or respiration is something all owners’ should know and is a primary indicator of the horse’s health. 5. CLINICALLY ASSESS YOUR HORSE. Owners know their horse and intuitively will pick when the horse is not himself. Investigate thoroughly any changes in signs, symptoms or behaviour.

6. RISK ANALYSIS. Always assess the situation and circumstances surrounding yourself and your horse and make a judgement as to the possible risk of a problem.

7. MAINTAIN A “PERIMETER” AROUND YOUR PROPERTY. Maintain a perimeter so that horses across the fence cannot contact each other.

8. “QUARANTINE” ANY NEW HORSES. A critical issue. Remember the incubation period (5-16 days) where an infected horse can appear normal. Isolate any new horses that arrive at your property.

9. STABLE HORSES or HOLD in “SAFE” YARDS at NIGHT if possible when flying foxes are most active.

10. IDENTIFY ALL PLANTS AND TREES. Know whether the trees on your property are food sources for flying foxes.

11. ELIMINATE FLYING FOX FOOD SOURCES. If you cannot remove dangerous plants or trees, at least fence them off or prevent your horse having any access. Make sure that food sources attractive to flying foxes such as fruit and vegetables are not left around horses.

12. FEED&WATER HORSES IN OPEN SPA

While waiting for test results:-

• Avoid close contact with the horse under investigation and other horses that have been in contact with it. Wait until your veterinarian has advised you of the test results.

• Isolate the horse that is under investigation from other animals if it is safe to do so. Ideally, leave the sick horse where it is and move other animals to a different area of the property.

• If you need to provide feed and water for any horses on the property, do this from a distance.

• Observe horses from a distance and notify your veterinarian immediately of any change in the health status of any horses on the property.

If the test result is negative, your veterinarian may wish to take further samples to investigate your horse’s illness. You should continue to monitor your horse and notify your veterinarian immediately of any change in the health status of any horses.

Queensland Premier Anna Bligh said the recent spike of cases in both states, as well as confirmation the potentially deadly disease had been found in a dog, meant research efforts needed accelerating. "Beating Hendra is going to take the combined effort of science around Australia, the community and the governments that are effected,"

In the meantime we horse and dog owners in Australia are living in fear every day that the horses we are riding or handling might be incubating deadly HeV and may also be giving this HeV death sentence to us and our dogs.

References

Biosecurity, Queensland Government at www.biosecurity.qld.gov.au

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation at http://www.abc.net.au/news/specials/hendra-virus/

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation at http://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-07-26/hendra-virus-infects dog/2811204/?site=brisbane§ion=news

The Brisbane Times at http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/environment/animals/dusty-the-dog-to-undergo-second-blood-test-20110727-1hzd3.html?from=brisbanetimes_sb

The Brisbane Times link to Research paper http://images.brisbanetimes.com.au/file/2011/07/27/2519505/Plowright%20et%20al%202008.pdf

The Department of Environment and resource Management at http://www.derm.qld.gov.au/wildlife-ecosystems/wildlife/living_with_wildlife/flyingfoxes/hendra_virus_faqs_relating_to_flying_foxes.html

Workplace health and safety, Queensland www.worksafe.qld.gov.au

Comments