17 percent of all sun-like stars have planets one to two times the diameter of Earth orbiting close to their host stars, according to a team of astronomers who created their estimate based on an analysis of the first three years of data from NASA's Kepler mission. Thousands of potential exoplanets have been detected, which is good news for those searching for habitable worlds outside our solar system.

To find planets, the Kepler telescope captures repeated images of 150,000 stars in a region of the sky in the constellation Cygnus. The data are analyzed by computer software in search of stars that dim briefly as a result of a planet passing in front, a transit. For planets as large as Jupiter, the star may dim by 1 percent, or one part in 100, which is easily detectable. A planet as small as Earth, however, dims the star by one part in 10,000, which is likely to be lost in the noise.

This estimate includes only planets that circle their stars within a distance of about one-quarter of Earth's orbital radius, well within the orbit of Mercury - the current limit of Kepler's detection capability. Further evidence suggests that the fraction of stars having planets the size of Earth or slightly bigger orbiting within Earth-like orbits may amount to 50 percent.

Planets one to two times the size of Earth are not necessarily habitable. Painstaking observations show that planets two or three times the diameter of Earth are typically like Uranus and Neptune, which have a rocky core surrounded by helium and hydrogen gases and perhaps water. Planets close to the star may even be water worlds – planets with oceans hundreds of miles deep above a rocky core.

Nevertheless, planets between one and two times the diameter of Earth may well be rocky and, if located within the Goldilocks zone – not too hot, not too cold, just right for liquid water – could support life.

"Kepler's one goal is to answer a question that people have been asking since the days of Aristotle: What fraction of stars like the sun have an Earth-like planet?" said Andrew Howard of the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii. "We're not there yet, but Kepler has found enough planets that we can make statistical estimates."

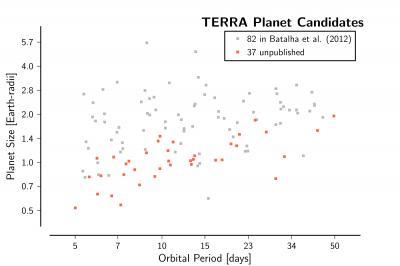

Each dot shows the orbital period and size of the 119 planet candidates found by Petigura, Marcy, and Howard using their custom transit search code, TERRA. The 82 gray dots represent planets previously discovered by the Kepler team and published in Batalha et al. (2012). The 37 red dots represent new planets found here, benefitting from an additional 18 months (six quarters) of NASA Kepler data. Note that most of the newly discovered planets are small, nearly the size of Earth. These newly discovered planets contribute to the final measured occurrence of Earth-size planets. Credit: Erik Petigura, Andrew Howard and Geoff Marcy

The estimates are based on a better understanding of the percentage of big Earth-size planets that Kepler misses because of uncertainties in detection, which the team estimates to be about one in four, or 25 percent.

U.C. Berkeley graduate student Erik Petigura spent the past two years writing a software program called TERRA, for Transiting Exoearth Robust Reduction Algorithm, which is very similar to Kepler's pipeline. They then fed TERRA simulated planets to test how efficiently the software detects Earth-size planets.

"It may seem crazy to spend two years redoing what the Kepler team has already done, but the question we are asking – How many Earth-size planets are we missing? – is so important that we wanted to do it separately for cross-validation," he said.

After measuring the fraction of planets missed by TERRA, the team corrected for this and conducted a thorough analysis of 12 of the 13 quarters of Kepler observations freely available on the Internet. They identified 119 Earth-like planets ranging in size from nearly six times the diameter of Earth to the diameter of Mars. Thirty-seven of these planets were not identified in previous Kepler reports.

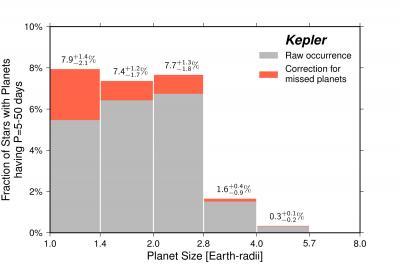

The fraction of sun-like stars having planets of different sizes, orbiting within 1/4 of the Earth-sun distance (0.25 AU) of the host star. The graph shows that planets as small as Earth (far left) are relatively common compared to planets 8.0x the size of Earth (similar to Jupiter). For example, 7.9 percent of sun-like stars harbor a planet with a size of 1.0-1.4 times the size of Earth, orbiting inward of 1/4 the Earth-sun distance (closer than Mercury's distance from the sun). There are increasing numbers of planets from 8x the size of Earth down to 2.8x Earth. Remarkably, the number of planets smaller than 2.8x Earth is approximately constant with planet size, down to the size of our Earth. The gray indicates the planets discovered in this study, and the orange represents the correction applied to account for planets the TERRA software would miss statistically, typically about 20 percent. Credit: Erik Petigura, Andrew Howard and Geoff Marcy

The analysis confirmed that the frequency of planets increases as the size decreases, which Howard and the Kepler team reported last year. Perhaps 1 percent of stars have planets the size of Jupiter, while 10 percent have planets the size of Neptune. Marcy compared this to rocks on a beach – large boulders are rare, stones are more common, and pebbles extremely abundant.

Unlike the beach, where sand grains and flecks are even more abundant, Petigura's team now estimates that the abundance of planets stops rising at about twice Earth's diameter and remains the same until the size of Earth, the limit of their analysis. This corrects an impression left by Howard's earlier paper that the frequency of Earth-size planets actually decreases below twice Earth's diameter.

"A year ago, Kepler had found only a few planets smaller than twice Earth's diameter, far fewer than would be expected if you extrapolate downward from the abundances of larger planets," Petigura said. Accounting for planets that Kepler misses still means that "big Earths" are one third as abundant as would be expected if the rising trend continued below twice the diameter of Earth.

Howard noted, however, that if 17 percent of all stars have Earth-size planets within the orbit of Mercury, "where are they in our solar system? Maybe our solar system is an anomaly compared to the great variety of stars."

Presented at a session on the Kepler mission during the American Astronomical Society meeting in Long Beach, California.

Comments