In November 2010, the distant dwarf planet Eris passed in front of a faint background star, an event called an occultation. Occultations provide the most accurate, and often the only, way to measure the shape and size of a distant Solar System body like Eris.

Eris was identified as a large object in the outer Solar System in 2005. Its discovery was one of the factors that led to the creation of a new class of objects called dwarf planets by the IAU and the demotion of Pluto from planet to dwarf planet in 2006. Eris is currently three times further from the Sun than Pluto.

The candidate star for the occultation was identified by studying pictures from the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at ESO's La Silla Observatory. The observations were carefully planned and carried out by a team of astronomers using, among others, the TRAPPIST (TRAnsiting Planets and PlanetesImals Small Telescope), also at La Silla.

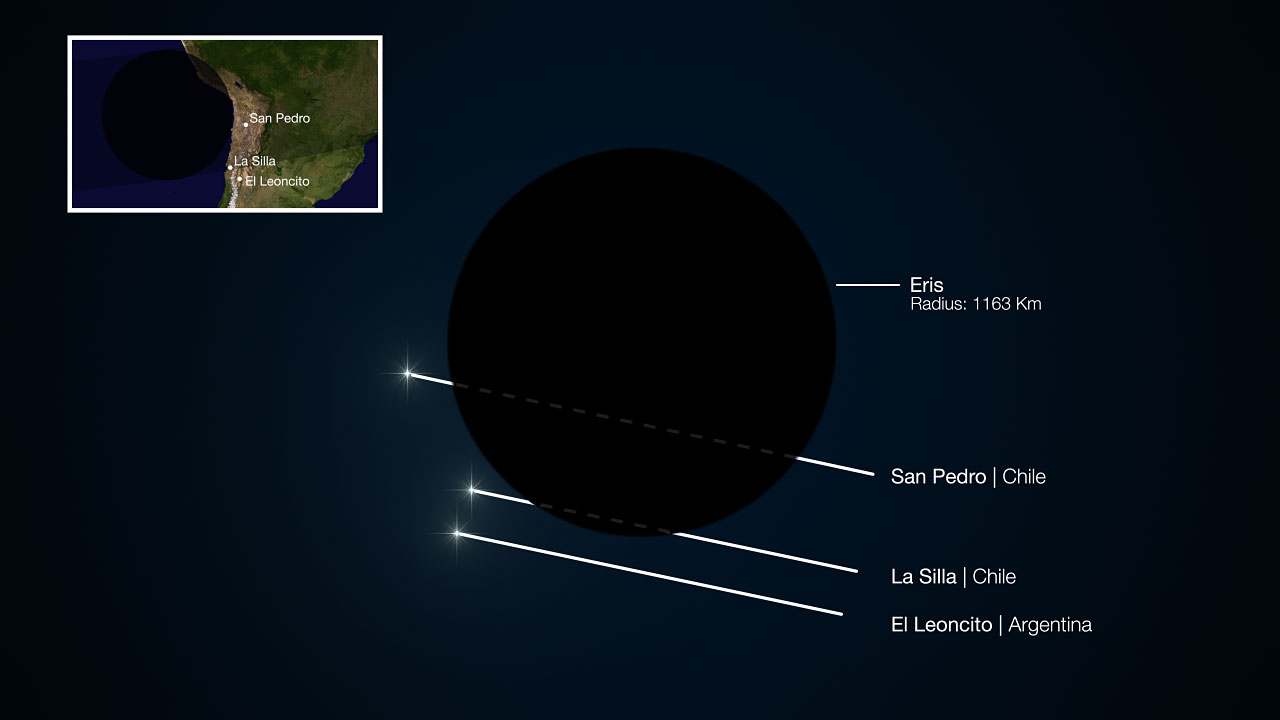

Observations of the occultation were attempted from 26 locations, including amateur observatories, around the globe on the predicted path of the dwarf planet's shadow. Two sites were able to observe the event directly, the La Silla Observatory using the TRAPPIST telescope, and San Pedro de Atacama using two telescopes. All three telescopes recorded a sudden drop in brightness as Eris blocked the light of the distant star.

The combined observations from the two Chilean sites indicate that Eris is close to spherical. These measurements should accurately measure its shape and size as long as they are not distorted by the presence of large mountains. Such features are, however, unlikely on such a large icy body.

"Observing occultations by the tiny bodies beyond Neptune in the Solar System requires great precision and very careful planning. This is the best way to measure Eris's size, short of actually going there," explains Bruno Sicardy, the lead author.

This artist's impression shows the distant dwarf planet Eris. New observations have shown that Eris is smaller than previously thought and almost exactly the same size as Pluto. Eris is extremely reflective and its surface is probably covered in frost formed from the frozen remains of its atmosphere. Credit: ESO/L. Calçada

While earlier observations using other methods suggested that Eris was probably about 25% larger than Pluto with an estimated diameter of 3000 kilometers, the new study proves that the two objects are essentially the same size. Eris's newly determined diameter stands at 2,326 kilometers, with an accuracy of 12 kilometers. This makes its size better known than that of its closer counterpart Pluto, which has a diameter estimated to be between 2,300 and 2,400 kilometers. Eris’s mass is 1.66 x 1022 kg, corresponding to 22% of the mass of the Moon.

Pluto's diameter is harder to measure because the presence of an atmosphere makes its edge impossible to detect directly by occultations. The motion of Eris's satellite Dysnomia was used to estimate the mass of Eris. It was found to be 27% heavier than Pluto. Combined with its diameter, this provided Eris's density, estimated at 2.52 grams per cm^3. For comparison, the Moon’s density is 3.3 grams per cm3, and water’s is 1.00 gram per cm3.

This diagram shows the path of a faint star during the occultation of the dwarf planet Eris in November 2010. Two sites in South America saw the faint star briefly disappear as its light was blocked by Eris and another recorded no change in brightness. Credit:ESO/L. Calçada

"This density means that Eris is probably a large rocky body covered in a relatively thin mantle of ice," comments Emmanuel Jehin, who contributed to the study. The value of the density suggests that Eris is mainly composed of rock (85%), with a small ice content (15%). The latter is likely to be a layer, about 100 kilometre thick, that surrounds the large rocky core. This very thick layer of mostly water ice is not to be confused with the very thin layer of frozen atmosphere on Eris’s surface that makes it so reflective.

The surface of Eris was found to be extremely reflective, reflecting 96% of the light that falls on it (a visible albedo of 0.96 [7]). This is even brighter than fresh snow on Earth, making Eris one of the most reflective objects in the Solar System, along with Saturn's icy moon Enceladus. The bright surface of Eris is most likely composed of a nitrogen-rich ice mixed with frozen methane — as indicated by the object's spectrum — coating the dwarf planet's surface in a thin and very reflective icy layer less than one millimeter thick.

Animation shows the path of the shadow of the dwarf planet Eris, cast by a faint star, as it crossed the Earth during the occultation of November 2010. The regions along the path saw the star briefly disappear as its light was blocked by Eris. Credit: ESO/L. Calçada

"This layer of ice could result from the dwarf planet's nitrogen or methane atmosphere condensing as frost onto its surface as it moves away from the Sun in its elongated orbit and into an increasingly cold environment," Jehin adds. The ice could then turn back to gas as Eris approaches its closest point to the Sun, at a distance of about 5.7 billion kilometers.

The new results also allow the team to make a new measurement for the surface temperature of the dwarf planet. The estimates suggest a temperature for the surface facing the Sun of -238 Celsius at most, and an even lower value for the night side of Eris.

"It is extraordinary how much we can find out about a small and distant object such as Eris by watching it pass in front of a faint star, using relatively small telescopes. Five years after the creation of the new class of dwarf planets, we are finally really getting to know one of its founding members," concludes Bruno Sicardy.

Comments