In the realm of quantum mechanics that is certainly be true, because microscopic objects can take different paths at the same time. Almost 100 years ago physicists Werner Heisenberg, Max Born and Erwin Schrödinger created this new field of physics which would be called quantum mechanics. Objects of the quantum world, according to quantum theory, no longer move along a single well-defined path. Rather, they can simultaneously take different paths and end up at different places at once. Physicists speak of quantum superposition of different paths.

But in the world we commonly experience the football always moves in one definite direction - unless the football is a caesium atom. Then it can take two paths at the same time, according to an experiment. At the level of atoms, objects indeed obey quantum mechanical laws. Over the years, many experiments have confirmed quantum mechanical predictions, but in our macroscopic daily experience, we know a football follows along exactly one path, it does not score a goal and misses at the same time.

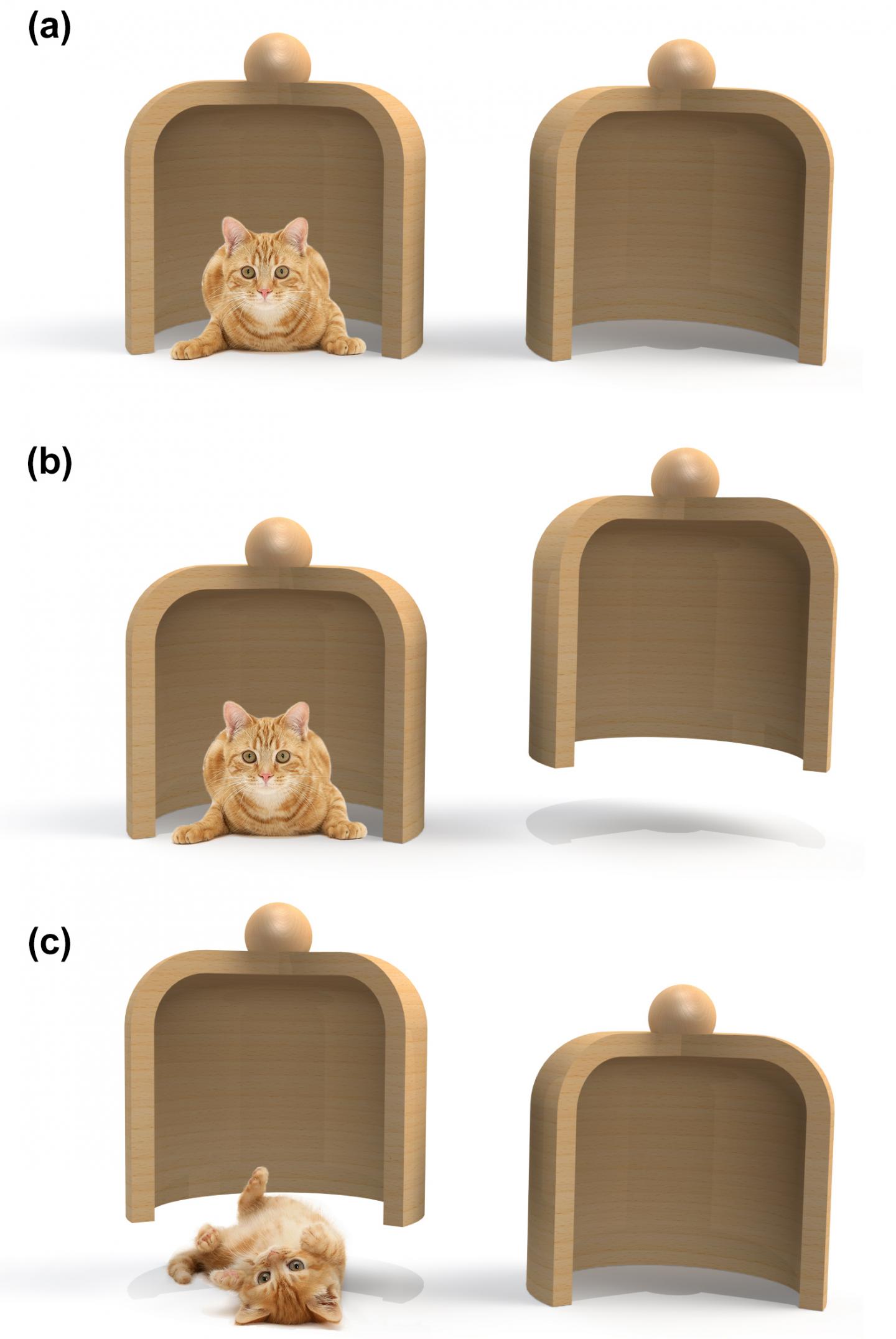

Let's assume that two containers are in front of us and a cat is hidden under one of them (a). However, we do not know under which one. We tentatively lift the right jar (b) and we find it empty. We, thus, conclude that the cat must be in the left jar and yet we have not disturbed it. Had we have lifted the left jar instead, we would have disturbed the cat (c), and the measurement must be discarded. In the macro-realist's world, this measurement scheme would have absolutely no influence on the cat's state, which remains undisturbed all the time. In the quantum world, however, a negative measurement that reveals the cat's position, like in (b), is already sufficient to destroy the quantum superposition and to influence the result of the experiment. The Bonn physicists have exactly observed this effect.

Credit. Andrea Alberti / www.warrenphotographic.co.uk

Why the disconnect between quantum behavior and macroscopic?

"There are two different interpretations," says Dr. Andrea Alberti of the Institute of Applied Physics of the University of Bonn. "Quantum mechanics allows superposition states of large, macroscopic objects. But these states are very fragile, even following the football with our eyes is enough to destroy the superposition and makes it follow a definite trajectory."

So "large" objects play by different rules. A football obeys completely different rules than those applying to single atoms. "Let us talk about the macro-realistic view of the world," Alberti explains. "According to this interpretation, the ball always moves on a specific trajectory, independent of our observation, and in contrast to the atom."

But which of the two interpretations is correct?

Do "large" objects move differently from small ones? In collaboration with Dr. Clive Emary of the University of Hull in the U.K., the Bonn team has come up with an experimental scheme that may help to answer this question. "The challenge was to develop a measurement scheme of the atoms' positions which allows one to falsify macro-realistic theories," adds Alberti.

With two optical tweezers they grabbed a single Caesium atom and pulled it in two opposing directions. In the macro-realist's world the atom would then be at only one of the two final locations. Quantum-mechanically, the atom would instead occupy a superposition of the two positions.

"We have now used indirect measurements to determine the final position of the atom in the most gentle way possible," says the PhD student Carsten Robens. Even such an indirect measurement (see figure) significantly modified the result of the experiments. This observation excludes - falsifies, as Karl Popper would say more precisely - the possibility that Caesium atoms follow a macro-realistic theory. Instead, the experimental findings of the Bonn team fit well with an interpretation based on superposition states that get destroyed when the indirect measurement occurs. All that we can do is to accept that the atom has indeed taken different paths at the same time.

"This is not yet a proof that quantum mechanics hold for large objects," cautions Alberti. "The next step is to separate the Caesium atom's two positions by several millimetres. Should we still find the superposition in our experiment, the macro-realistic theory would suffer another setback."

Citation: Carsten Robens, Wolfgang Alt, Dieter Meschede, Clive Emary und Andrea Alberti: Ideal negative measurements in quantum walks disprove theories based on classical trajectories; Physical Review X, 20.1.2015 DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevX.5.011003

Comments