Research has previously believed that animals and plants developed different genetic programs for cell death.

For plants and animals, and for humans as well, it is important that cells both can develop and die under controlled forms. The process where cells die under such forms is called programmed cell death. Disruptions of this process can lead to various diseases such as cancer, when too few cells die, or neurological disorders such as Parkinson's, when too many cell die.

The findings are published jointly by research teams at SLU (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences) and the Karolinska Institute, the universities of Durham (UK), Tampere (Finland), and Malaga (Spain) under the direction of Peter Bozhkov, who works at SLU in Uppsala, Sweden.

The scientists have performed comparative studies of an evolutionarily conserved protein called TUDOR-SN in cell lines from mice and humans and in the plants norway spruce and mouse-ear cress. In both plant and animal cells that undergo programmed cell death, TUDOR-SN is degraded by specific proteins, so-called proteases.

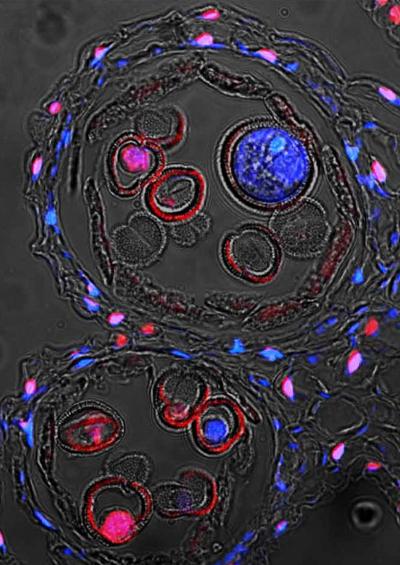

In both plant and animal cells that undergo programmed cell death, the protein TUDOR-SN is broken down. In pollen, from the model plant mouse-ear cress, a reduction in TUDOR-SN leads to fragmentation of DNA (red signal) and premature cell death. Credit: SLU

The proteases in animal cells belong to a family of proteins called caspases, which are enzymes. Plants do not have caspases – instead TUDOR-SN is broken down by so-called meta-caspases, which are assumed to be ancestral to the caspases found in animal cells. For the first time, these scientists have been able to demonstrate that a protein, TUDOR-SN, is degraded by similar proteases in both plant and animal cells and that the cleavage of TUDOR-SN abrogate its pro-survival function. The scientists have thereby discovered a further connection between the plant and animal kingdoms. The results now in print could play a role in future studies of this important protein family.

Cells that lack TUDOR-SN often experience premature programmed cell death. Furthermore, functional studies at the organism level in the model plant mouse-ear cress show that TUDOR-SN is necessary for the development of embryos and pollen. The researchers interpret the results to mean that TUDOR-SN is important in preventing programmed cell death from being activated in cells that are to remain alive.

The research teams maintain that the findings indicate that programmed cell death was established early on in evolution, even before the line that led to the earth's multicellular organisms divided into plants and animals. The work also shows the importance of comparative studies across different species to enhance our understanding of how fundamental mechanisms function at the cellular level in both the plant and animal kingdoms, and by extension in humans.

Comments