But choice and competence are prevalent in funding discussions too. Yet funding representation is a much greater problem than gender, race or political representation - it impacts all of health in chronic fashion. New York state received 20 percent of all Medicare’s graduate medical education funding - and that meant 29 other states, including places with a severe shortage of physicians, got less than 1 percent, according to a report published last year by researchers at the George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services (SPHHS).

What about fairness?

New York can claim that it simply does better work training doctors - a fair argument, but it is in defiance of the whole premise of equality, which posits that social diversity will lead to better people overall. And how can other states produce quality doctors when they are starved by political interests catering to New York lobbyists?

New York certainly suffers from no lack of physicians yet in 2010 the state received $2 billion in federal GME funding according to the study, while many states struggling with severe physician shortages received a fraction of that funding: For example, Florida received one tenth the funding of New York ($268 million) and Mississippi, the state with the lowest ratio of doctors to patients in the country, received just $22 million in these federal payments.

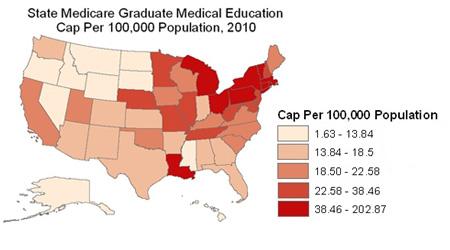

The number of Medicare-sponsored medical residents per 100,000 people, per state. Credit: GWU

“Such imbalances play out across the country and can affect access to health care,” said lead author Fitzhugh Mullan, MD, a Professor of Medicine and Health Policy at George Washington University. “Due to the rigid formula that governs the GME system, a disproportionate share of this federal investment in the physician workforce goes to certain states mostly in the Northeast. Unless the GME payment system is reformed, the skewed payments will continue to promote an imbalance in physician availability across the country.”

The study adds to the evidence suggesting that the current system of allocating graduate medical education. Since its start, the Medicare GME program has paid teaching hospitals to provide residency training for young physicians. In 2010, those teaching facilities received $10 billion in GME payments, an amount that represents the nation’s single largest public investment in the health workforce.

To find out how that $10 billion was distributed, the researchers analyzed the 2010 Medicare cost reports that list federal GME payments to teaching hospitals all over the country. The team found a disproportionate amount of Medicare GME dollars flowing to Northeastern states such as New York, Massachusetts and Rhode Island. In fact, the study shows that in these three states Medicare supports twice as many medical residents per person as the national average. And New York alone has more residents than 31 other states combined.

“Teaching hospitals in the Northeastern United States have a long history of large residency training programs, which capture a large share of GME funding,” Mullan said. “But these states also have the highest physician-to-population ratios. They are not doctor shortage states.”

While some residents move elsewhere after training, the majority of newly minted physicians set up a practice near where they were trained. Therefore, it is important that states with rural and growing populations receive appropriate support for starting and maintaining residency programs, Mullan said.

The study shows that many other parts of the country lose out when it comes to Medicare GME funding. Many Southern and Western states—which already face shortfalls in their physician workforce—such as Montana, Idaho, Arkansas, Wyoming, Florida and even California do not do well in terms of Medicare GME funding under the current system, according to the authors.

The researchers also found:

- Large state-level differences in the number of Medicare-funded medical residents even when the density of the population is taken into account. For example, New York again is at the top of all the states with 77 Medicare-funded medical residents per 100,000 people while California has 19, Florida 14, and Arkansas has just 3.

- Medicare GME payments have not kept pace with factors such as rapidly growing populations in Southern and Western United States. For example, Florida, Texas and California have rapidly growing populations yet they received substantially less GME funding in 2010.

- Medicare’s current GME formula pays very different amounts to train medical residents depending on the state. For example, the federal government pays Louisiana $64,000 per year to train each medical resident but gives Connecticut $155,000 for the same job.

The findings from this paper document a substantial imbalance in GME payments, one that has been frozen in place since 1997 when Congress passed a law that capped the number of residency positions at each hospital. Under the 1997 law, teaching hospitals can train any number of physicians but Medicare pays for the training only up to the allocated cap, the authors point out.

The end result of the cap and other inflexible attributes of the current GME system is a system that gives teaching hospitals in certain states with large numbers of practicing physicians big incentives to train more residents while shortchanging many smaller and rural states.

Ways to fix the problem include revisiting the GME payment formula and devising one that distributes GME funding so as to stimulate the growth of residency training in parts of the country that are chronically underserved or are growing rapidly. In addition, the authors say the GME funding system needs an oversight body that would look now and in the future at the distribution of GME dollars and make decisions about the best places to steer funding so that the federal government is making the wisest investment in the physician workforce.

Article: “The Geography of Graduate Medical Education: Imbalances Signal Need for New Distribution Policies,” Health Affairs.

Comments