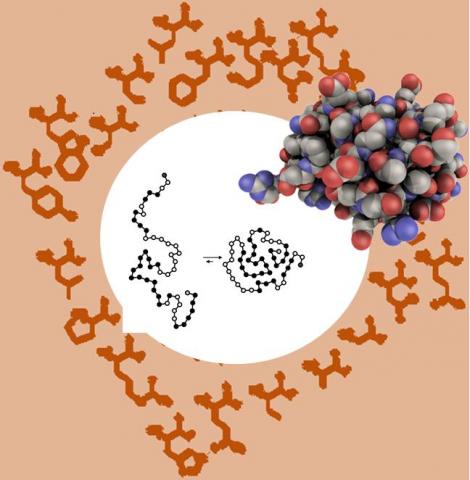

All life, from bacteria to blue whales to human beings, uses an almost universal set of 20 coded amino acids to construct proteins. This set was likely "canonicalized" or standardized during early evolution; before this, smaller amino acid sets were gradually expanded as organisms developed new synthetic proofreading and coding abilities. There are millions of possible types of amino acids that could be found on Earth or elsewhere in the Universe, each with its own distinctive chemical properties.

1 in a billion

Scientists have found these unique chemical properties are what give biological proteins, the large molecules that do much of life's catalysis, their own unique capabilities.

The coded amino acids each have unique properties that help biological proteins fold optimally. The set of amino acids biology uses appears to have been evolutionarily optimized.

Image: H.J. Cleaves, ELSI/ Wikimedia Commons

A team created a study to find answers. They had previously measured how the CAA set compares to random sets of amino acids and found that only about 1 in a billion random sets had chemical properties as unusually distributed as those of the CAAs. One in a billion is entirely manageable when we are talking about millions of amino acids over billions of years in an infinite universe. It's even likely.

The team thus set out to ask the question of what earlier, smaller coded sets might have been like in terms of their chemical properties. There are many possible subsets of the modern CAAs or other presently uncoded amino acids that could have comprised the earlier sets. They calculated the possible ways of making a set of 3-20 amino acids using a special library of 1913 structurally diverse "virtual" amino acids they computed and found there are 1048 ways of making sets of 20 amino acids.

In contrast, there are only ~ 1019 grains of sand on Earth, and only ~ 1024 stars in the entire Universe.

"There are just so many possible amino acids, and so many ways to make combinations of them, a computational approach was the only comprehensive way to address this question," says team member Jim Cleaves of ELSI. "Efficient implementations of algorithms based on appropriate mathematical models allow us to handle even astronomically huge combinatorial spaces," notes co-author Markus Meringer of the Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt.

As this number is fantastically large, they used statistical methods to compare the adaptive value of the combined physicochemical properties of the modern CAA set with those of billions of random sets of 3-20 amino acids. What they found was that the CAAs may have been selectively kept during evolution due to their unique adaptive chemical properties, which help them to make optimal proteins, in turn helping organisms that could produce those proteins become more fit.

They found that even hypothetical sets containing only one or a few modern CAAs were especially adaptive. It was difficult to find sets even among a multitude of alternatives that have the unique chemical properties of the modern CAA set. These results suggest that each time a modern CAA was discovered and embedded in biology's toolkit during evolution, it provided an adaptive value unusual among a huge number of alternatives, and each selective step may have helped bootstrap the developing set to include still more CAAs, ultimately leading to the modern set.

If true, the researchers speculate, it might mean that even given a large variety of starting points for developing coded amino acid sets, biology might end up converging on a similar set. As this model was based on the invariant physical and chemical properties of the amino acids themselves, this could mean that even Life beyond Earth might be very similar to modern Earth life. Co-author Rudrarup Bose of the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden, further hypothesizes that "Life may not be just a set of accidental events. Rather, there may be some universal laws governing the evolution of life."

Comments