The metronome seems such a simple thing, just a machine that goes tick tick, and you then play in time with it. So, why is it that beginner musicians often have so much difficulty keeping in time with it? And why is it that humans find it hard to play like a metronome, why doesn't that come natural to us?

Many musicians and entire musical cultures with a wonderful sense of rhythm don't use a metronome at all. Yet many western musicians spend hours every day with the tool. Do we need it, does it help - and if so what's the best way to work with a metronome? And what about ways of working on rhythm without using a metronome at all?

I'm the developer of Bounce Metronome, which uses techniques from conducting to help musicians to work with a metronome in a relaxed, precise and enjoyable way.

Here is Tim Vine poking gentle fun at the musician's love hate relationship with a metronome

Humans seldom play music at an exact tempo with all the beats the same. It's like breathing and running, and walking. Just as we don't walk in exact time like a robot, so we don't sing like that either.

Here is a recording of Efe people ("pygmies") playing rhythms, wonderful sense of rhythm - but surely never touched a metronome

Efe Peoples Music, Indigenous Africa, Likembe Song

Many musicians to this day are still under the impression that the way to use a metronome is simply to play your music with it - over and over - and hope that somehow that helps you to play a more steady tempo and more precise rhythms.

But then, give that a go, and you find it almost impossible to play exactly in time with it, and at the same time in a musically expressive fashion. So then you might decide, the metronome is a useless tool and forget about it.

What Frederick Frank said in his little book on Metronome Technique published in 1947 still holds true today.

There are two schools of thought among musicians concerning this use of the metronome—one opposed and the other favorable. "Practicing with a metronome" has been criticized by some musicians as "making you mechanical." In some instances such criticism is largely a prejudice, the critic having gained the impression that one starts a metronome and simply continues playing with it indefinitely. In most instances, however, such criticism is excusable since so little has been published on specific techniques of metronome uses. It is hoped that those who oppose its use for learning and improving the control of rhythm will read with tolerance these methods, employed by those who favor it, and perhaps investigate their value by experimenting with one or two of them in their own teaching or preparation for concerts.

And indeed, many musicians and composers have criticized use of a metronome, sometimes going so far as to say that nobody should use a metronome.

However even today, more than 65 years after he published his little book, nearly all the criticisms of metronome practice are based on the idea that you play your music along with the metronome indefinitely, or try to play in metronome like rhythms, both ideas that are easy to find fault with. See for instance the criticism section of the Wikipedia article on the metronome for many quotes.

As far as I know, his was the first book to cover metronome technique in detail. However there have been at least two more books on it since then, the books by Mac Santiago and Andrew Lewis.

Many musicians and music teachers are unaware of this past research, and often end up re-inventing some of the techniques from scratch themselves.

I'm the developer of Bounce Metronome and was also completely unaware of this until a few years back, when I started to research into it as background research for my software, talked over the ideas with musicians and music teachers, tried out the ideas myself and built them into the metronome.

There are many exercises you can use with a metronome. The underlying idea of them all, however, is to develop independence of the metronome, and to help you to rely more and more on your own inner sense of rhythm and tempo.

If your metronome exercises aren't continually helping you to rely on your own inner sense of rhythm and tempo, I think it is probably reasonable to say that you are not making best use of the metronome - and may well be making your timing issues worse.

PLAYING IN THE POCKET

Musicians talk about playing "in the pocket" meaning right on the beat, neither ahead nor behind. This seems to be the key to metronome technique, to be able to play in the pocket with a metronome - and to do so in a relaxed and enjoyable way.

Try this exercise to get started, and you may well find it much harder than you expected. If so that's normal.

Remember, these are just exercises, and the aim is not to learn to play music like this, but rather, the idea is that by doing exercises like these, you can become more sensitive to nuances of time and rhythm, and feel them more strongly in yourself.

The rhythm and sense of tempo is something you have in yourself. You may have an excellent connection with it already and not need these exercises, but if not, it's possible these exercises might help.

Or for an easier exercise, Mac Santiago's decreasing tick - again - can you keep in time with the metronome, in the pocket, and merge with it - all the way through to silence?

Or for a real toughy, his diminishing click, a very challenging exercise

With all these exercises, are you still "in the pocket" with the click when it returns after the silence? You may well find it is far harder than you expected, to be completely in time.

If you think you are in time, listen carefully, ask if you could be slightly ahead or behind the click. Helps to play something really distinct and percussive, e.g. tap with a stick on a hard stone or edge of a drum.

You might then find that you hear a slight double tap, of your tap and the metronome click - not just a single merged click.

The problem is, as you get close to the metronome clicks, your clicks merge with the taps - and vanish - when you most need to hear them! With loud instruments like drums or percussion, the metronome may seem to stop clicking altogether for a few beats, for as long as you can keep "in the pocket".

So, there's a strong natural tendency to play a little way away from the click, behind or ahead of it, so you can hear the click. If you haven't paid much attention to this, you'll probably find that you've got into the way of playing ahead or behind the metronome click, or randomly sometimes one and then the other.

This is frustrating to start with. How can we stay in time with this pesky metronome, when the click vanishes when we most need it?

Drummers particularly tend to deal with it using extremely loud metronome clicks (possibly even risking damage to ears) or using beeps, which are perhaps not so percussive so not so precise to listen to, but easier to hear.

VANISHING CLICK - OR RATHER, MERGING CLICK

However, the whole thing changes once you realize that you can make this vanishing click the aim of your exercise. The click doesn't literally vanish of course. It's more of a merge than a vanish. You can learn to listen out for that merge, which has a distinctive sound of its own. This turns it around so that you are continually being pulled towards the click.

So, that's what we aim to achieve with the exercises. But don't expect to do it right away, it takes a while. Especially it may take a while to be relaxed when you play in the pocket with the metronome click like this - to be able to do that in a completely relaxed way.

To help with relaxation, especially if you have got tense through much metronome practice in the past - one nice exercise is to alternate with the metronome. Like you play alternate beats, with the metronome set to a really slow tempo. Hopefully that will be relaxing, and - that also gives a good idea of how relaxing metronome practice can be. All the other exercises can be as relaxing as this.

The basic technique then, to help you to hear the merge more clearly - is to play ahead of the beat, deliberately, then behind it, then once you have "bracketted" it by playing to either side, to play in the between those two points - just go for it, for the point in between, in a relaxed way - and see if you hit it - and listen out for this merge sound as you do so.

You an approach that gradually also - start in the middle of the beat, then play close to it but not too close, then gradually closer to it, to either side, and then from time to time try playing between the two.

Once you've got the hang of that, you can also try playing really close to the metronome to either side. There I found a tip that helps, is to think in terms of - first an echo. Think of your click as the echo, then think of the metronome as an echo. We are used to echoes, and they are relaxing also - this helps you to relax and feel clear about which side of the click you are.

Then you can think in terms of reverb also - so close it doesn't feel like an echo any more but more like a subtle reverb, you are the reverb for the metronome, and vice versa. Then again play in the middle, so neither you nor the metronome is the reverb, but you play together as one.

You might also find that the visual bounce effects of Bounce Metronome like the motion of a conductor's baton, or drum stick, help you to relax and find the click easily.

I did a series of videos on this a while back: Enjoyment, Relaxation and Precision in Metronome Technique, with other ideas and exercises to try. And read here The Vanishing Metronome Click - Burying the Click

If you liked the go silent briefly exercises, and would like more challenges like that, including polyrhythmic silences, and the extremely challenging rhythmic phasing silences, you'll find several more here: How Steady is Your Tempo? - Test With Go Silent Briefly

I'm just an amateur player, sharing ideas I've found in my research, I've had many emails from musicians saying how helpful they find these videos and descriptions, which is why I have courage to share this. If you hear mistakes, well that's just me, don't expect me to be perfect like a pro musician - but the ideas are powerful and good ones, and hopefully I've described them well.

If you want to follow it up further, you can find plenty of material in the books by music teachers mentioned later.

CONDUCTING METRONOME

When you show the time visually, then you don't have the same issues of the metronome masking the sound of your instrument.

That leads to the idea of a purely visual metronome. But one that just flashes as some do - or displays numbers that change in an instant at the start of the beat - is very hard to keep really precise time with. There's no lead into the flash, no precise advance warning of when the next beat will be. It's not easy to play in the pocket with a metronome like that.

The answer to this came from study of technique used by conductors. They are often advised to think of the baton as "bouncing off an invisible horizontal plane"

"The motion is like bouncing a golf ball on pavement. Your performers must be trained to play exactly at the bottom of the beat." P 19, Brock McElheran, "Conducting Technique for beginners and professionals", revised edition (1989).

There is a lot more to it than that of course. See also Conducting, a Hands On Approach, by Anthony Maello - which you can read, much of it, online as a Google book

However, it wasn't my aim to try to imitate the way conductors move their baton. Indeed, you might be able to show time more precisely on a computer screen. With a baton, then you can't change direction instantly, instead the baton has to slow down slightly, make a little loop, and then the conductors use a fast "ictus" rebound to show the time as precisely as they possibly can.

But, on the screen you can show a true bounce just like bouncing a golf ball off a pavement in the Brock McElheran quote. So why program in movements that arise from limitations of what a human hand can do?

Indeed one conductor has suggested the idea of using a visual display in place of a human conductor for greater precision of synchronization of the orchestra. This is Josan Aramayo with his Sine Metronome which he used to conduct an orchestra. He worked this through with many details to help performers to follow his metronome like a real conductor, but with greater precision of the movement of the baton.

I'm not attempting to do that here though. With Bounce Metronome, the aim is just to indicate the time as precisely as possible for a simple metronome - not to use it to generate baton movements to conduct an orchestra following a score with all its nuances of timing and articulation etc. So just a simple bounce action is sufficient.

You might like the blog post I wrote back in 2008, on the very day when I had this idea, for the first time, to program a bouncing ball conducting metronome.

For some time I’ve wondered about what to do about visuals for the metronome. I could do an animation of a conventional metronome, but that’s a bit boring in a way, not really designed for the screen, as the display is limited to the mechanics of a real metronome. I may do that at some point.Here is a video of Sorlo, a bouncing sorcerer. I think the sense of fun is important to help you relax, and enjoy your practice sessions, which is why I was so keen to get sprites working in the program, for those who asked for them.

I also wondered about an animation of a conductor conducting the beat, hands moving around in patterns to follow the metronome. That’s much more flexible and could be fun to do. The challenge here is to keep the design simple and easy to follow, yet interesting.

So, today, while thinking about how to program a conductor’s hands, I had the idea of a bouncing ball – that programmer’s stalwart. It’s very similar – with the upbeat the conductor raise his or her hand and it moves in a trajectory very like the bounce of a bouncing ball, speeding up as it reaches the bottom of the beat.

Robert the Inventor's Software Blog, 2008

“There's something about the bounce that keeps the practicing vibrant. It's a great and fun tool.”, Dan Axelrod - read more »”

“...their rise and fall incorporates a ‘gravity bounce’ that feels like having your own conductor to help you keep in time. ...”

Martin Walker Sound On Sound Magazine - reviewYou might notice in the video how Sorlo jumps far higher before the first beat in the measure, and also does a higher jump across from side to side between the second and third beats.

That's another technique from conducting. It helps you to see exactly where you are, with just a glimpse out of the corner of your eye - and pay most of your attention to the music. That's just as useful when you practice with a metronome as with a conductor.

As an interesting historical note, the first "baton metronome" was a mechanical device built by Treadway Hansom in 1886

"It occurred to me that a metronome might be made to do all that the usual well known one does - and something more; that is, not only mark the several beats in each bar, distinguising the first by means of a bell, and leaving all the others exactly alike, but give each beat in the same manner as a conductor does with his baton.

Nothing more than this is, of course, claimed for it. It is but mechanical and has the limitations inseparable from mechanism, and can only be of use for the practice of students when no conductor is present.

Still you may possibly think there may be some advantage in students becoming accustomed to the various beats of a baton, and learning to attach a meaning ot each of them.

The sound of the bell and the click of the ordinary instrument are both avoided, whih may be of advantage also, especially in singing practice."

From his 1893 presentation to the Musical Association

Diagram from his 1894 patent for a mechanical baton metronome

METRONOMES AND CLICK TRACKS WON'T GIVE YOU A WONDERFUL SENSE OF RHYTHM

When did you last come into a room with a metronome clicking away and say "what a wonderful sense of rhythm that metronome has" :). Just doesn't happen, Though metronomes keep wonderfully exact time, they don't sound especially rhythmical in any wonderful way to us.

That wonderful sense of rhythm is something that will come from you, and you can't get it from a metronome.

See for instance the tempo plots here: revisiting the click track

In most musically expressive playing, the tempo varies continually, for instance here is a tempo plot of the Moonlight Sonata as played by Maurizio Pollini

You can almost always tell if the music is played to a click track from the tempo plot. If you want to play to a click track, fine, if that's the sort of music you want to make. But the idea you sometimes get - that playing like a click track is the ideal form of music, that that's what everyone should aim for, that's just plain silly I think :).

One of the things you come across as a programmer involved in algo-comp is the need to try to make it so the computer sounds less like a metronome and more like a human player. As a programmer of fractal tunes, with Tune Smithy, I have spent a fair bit of time trying to bring more nuanced rhythms and tempo into the music, to help it to sound much more interesting and lively to the listener.

Similarly as a musician, you need to encourage fluid rhythms, not try to fit your playing into a straight-jacket of a steady tempo. That is unless your aim is indeed to play like a metronome.

Here is an example of someone doing his best to become a human metronome. But I think, as a joke.

Alem with the metronome - a kind of "human metronome"

And here, Maria Callas, a singer who most assuredly doesn't sing like a metronome :)

And here Jacqueline Du Pre, playing the Elgar Cello Concerto first movement

You can follow the score here, notice how almost every eighth and sixteenth note in her opening varies in timing, with expressive rubato.

HOW TO ENCOURAGE NATURAL FLUID RHYTHMS

If you do use a metronome, then I think it's good practise to try some of these things, to encourage the fluidity and natural human rhythms - especially if you practise with the metronome for hours a day.- Play ahead and behind the beat, deliberately, try playing in different places in the beat

- Try "drifting through the beat" so you start, say, immediately after the beat, and then gradually drift further and further away until you are just in front of the next beat

- Play polyrhythmically along with the metronome. E.g. set it to play 3 beats to the measure, and play along at 4 beats to a measure.

- Practise at many tempi including fractional bpm so you don't get locked into playing at a particular tempo such as say 60 bpm.

- Practise with the metronome set to change tempo gradually, to encourage smooth and fluid changes of tempo.

- Switch off the sound, when using a visual metronome like Bounce Metronome, so you have the visual cues still but not the metronome click. It might help you vary your timing relative to the metronome.

I don't think most musicians need to worry too much that they will turn into a human metronome. It takes a lot of dedication to do that. It's like trying to learn to walk like a robot. You might learn to do it well enough for a part in a science fiction movie, but as soon as you finish your scene, you'll be back to your normal irregular way of walking.

However, exercises like these might help with fluidity of the rhythms - and feeling really comfortable moving around in the beat. They are a bit like stretching exercises to keep your muscles flexible in physiotherapy.

LIKE AN ARTIST LEARNING TO DRAW STRAIGHT LINES AND CIRCLES FREEHAND

This is an ancient story about artists who could draw perfect lines and circles. Goes back to Apelles, in a story by Pliny,

"Apelles arrived one day on the island of Rhodes to see the works of Protogenes, who lived there. Protogenes was not in his studio when Apelles arrived. Only an old woman was there, keeping watch over a large canvas ready to be painted. Instead of leaving his name, Apelles drew on the canvas a line so fine that one could hardly imagine anything more perfect.

On his return, Protogenes noticed the line and, recognizing the hand of Apelles, drew on top of it another line in a different color, even more subtle than the first, thus making it appear as if there were three lines on the canvas. Apelles returned the next day, and the subtlety of the line he drew then made Protogenes despair. That work was for a long time admired by connoisseurs, who contemplated it with as much pleasure as if, instead of some barely visible lines, it had contained representations of gods and goddesses"

And Giotto's perfect circle, and this wonderful story about the perfect crab

Among Chuang-tzu's many skills, he was an expert draftsman. The king asked him to draw a crab. Chuang-tzu replied that he needed five years, a country house, and twelve servants. Five years later the drawing was still not begun. "I need another five years," said Chuang-tzu. The king granted them. At the end of these ten years, Chuang-tzu took up his brush and, in an instant, with a single stroke, he drew a crab, the most perfect crab ever seen.

See Giotto's circle, Apelles' lines, Chuang-tzu's crab

Whether any of these things actually happened is another matter. But it is possible to draw a perfect circle freehand. Nowadays it seems more a sport of mathematicians than artists, but it can be done. See

He made this up, as a story to tell his students - but then eventually they actually did hold a freehand circle drawing championship, in Canada, which he won. Interview with him on the Today show.

Whether or not any great artists of the past or present have this same ability or worked on it - I think it makes a good analogy with metronome practice.

Practising with a metronome and learning to perform a perfectly steady tempo is rather like this ability to draw a perfect circle.

It doesn't make you a better musician. But it helps you to work on timing and co-ordination, to become more sensitive to tempo and rhythm, which some musicians may find helpful, others don't need to do it.

EXERCISES THAT DON'T INVOLVE A METRONOME

Andrew Lewis particularly talks about these. You can do without a metronome altogether if you use these methods - or you can use it to complement your metronome practice.

This section is taken pretty much word for word from the Wikipedia article on the Metronome - I contributed a fair bit to this part of it, in collaboration with another editor who was keen on Entasis and found the academic sources for it for the article. It also draws on some material I contributed to the Wikipedia article on Notes inégales

One starting point is to notice that we rely on a sense of rhythm to perform ordinary activities such as walking, running, hammering nails or chopping vegetables. Even speech and thought has a rhythm of sorts. So one way to work on rhythms is to work on bringing these into music, becoming a "rhythm antenna" in Andrew Lewis's words.

Until the nineteenth century in Europe, people used to sing as they worked, in time to the rhythms of their work. Musical rhythms were part of daily life, Cecil Sharp collected some of these songs before they were forgotten. For more about this see Work song and Sea shanties. In many parts of the world music is an important part of daily life even today. There are many accounts of people (especially tribal people) who sing frequently and spontaneously in their daily life, as they work, and as they engage in other activities.

"Benny Wenda, a Lani man from the highlands, is a Papuan leader now in exile in the UK, and a singer. There are songs for everything, he says: songs for climbing a mountain, songs for the fireside, songs for gardening. "Since people are interconnected with the land, women will sing to the seed of the sweet potato as they plant it, so the earth will be happy." Meanwhile, men will sing to the soil until it softens enough to dig." (Songs and freedom in West Papua)

Musicians may also work on strengthening their sense of pulse using inner sources, such as breath, and subdividing breaths. Or work with the imagination, imagining a pulse. They may also work with their heart beat, and rhythms in their chest muscles in the same way, ( Andrew Lewis Rhythm - What it is and How to Improve Your Sense of It)

Another thing they do is to play music in their mind's ear along with the rhythms of walking or other daily life rhythms. Other techniques include hearing music in ones mind's ear first before playing it. Musicians can deal with timing and tempo glitches by learning to hear a perfect performance in their mind's ear first.

UNEVEN NOTES IN MEDIEVAL MUSIC - WAS IT REGULAR LIKE MODERN JAZZ, OR CONTINUOUS SURPRISE?

This is an idea from early music notes inégales, according to one minority view interpretation.. It is an approach that doesn't work so much with a sense of inner pulse and instead builds the music out of gestures and is more closely related to the rhythms of speech and poetry.

The basic ideas are -

- Notes should be subtly unequal - having no three notes the same helps to keep the music alive and interesting and helps prevent any feeling of sameness and boredom in the music - the idea of "Entasis"

"This technique is especially challenging in its application, because musicians today are so rigidly trained in metrical regularity.

Yet, like the beating of the heart, the musical pulse needs to fluctuate in speed as the emotional content of the music fluctuates. Like the natural shifting accents in speech, musical accents need to shift according to the meaning being expressed. To feel perfect, music must be metrically imperfect."

- Notes and musical phrases can be organized in gestures – particular patterns of rhythm that come naturally – rather than strict measures.

- Individual notes can be delayed slightly – when you expect a particular note e.g. at the end of a musical phrase – just waiting a moment or two before playing the note:

"The cognitive partner of hesitation is anticipation: anticipation is created by building up assumption on assumption about what will happen. When the event which should occur fails to happen at the expected time, there exists a moment of disappointment.

Disappointment, however, is soon transformed into a rush of pleasure when the anticipated event is consummated. The art is always in the timing."

- Notes played together can be allowed to go somewhat out of time with each other in a care-free fashion "Sans souci".

"When the alignment of notes in the score suggests that they be performed strictly and simultaneously, they may be purposely jumbled or played in an irregular or a staggering manner to create a careless (sans souci) effect. This technique gives music a feeling of relaxed effortlessness"

The quotes there are from Marianne Ploger and Keith Hill The Craft of Musical Communication Orphei Organi Antiqui 2005

This just touches on some of the ideas; for more details, see their article.

This is a minority view on interpretation of Notes inégales but well worth a mention here because of its different approach to musical time and rhythm, and its relevance to the way rhythms can be practised.

THE MECHANICAL CLOCKS INTERPRETATION

This is the view that Notes inégales were played with a steady swing, like modern Jazz.

The main evidence from this comes from early mechanical clocks that were constructed to play Notes Inegales, and a treatise on the technique of pinning for mechanical organs. See: Dirk Moflants The Performance of Notes Inegales: The Influence of Tempo, Musical Structure, and Individual Performance Styleon Expressive Timing Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal Vol. 28, No. 5, June 2011

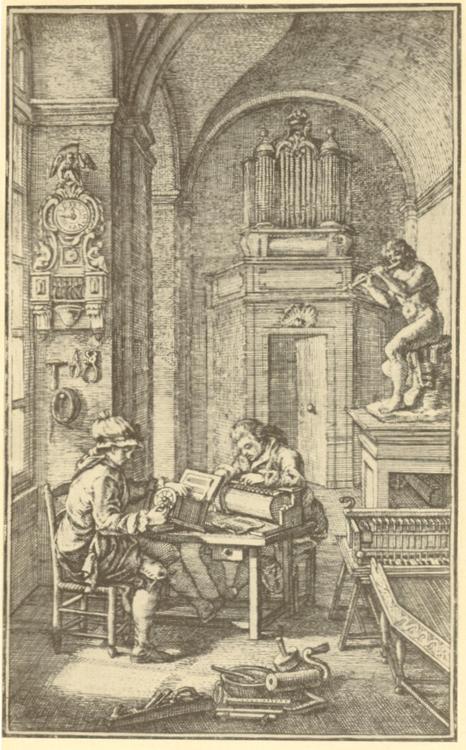

Frontispiece of Engramelle's La Tonotechnie, a treatise on construction of musical automata source of much of our information on timing details of Notes inégales. This image shows many different musical automata in his workshop

But on the other hand - that might just be because they were clocks, it might not reflect the way that ordinary musicians of the time played the music. Indeed Engramelle, main source for the exact ratios used, in his treatise on how to construct a mechanical clock, writes

"Inequalities... in many places vary in the same piece. It is left to fine taste to appreciate these variations of inequality."

Translation and excerpt from "Eighteenth-century Keyboard Music" by Robert Marshall.

Robert Marshall in his "Eighteenth Century Keyboard Music" writes

Musical automaton click mechanism as studied in Engramelle's La Tonotechnie - if you read french, you can read his original book online in google books.

"Understood proprely, the note inegales conventin represents an exceedingly refined form of rubato, one of such subtlety that it cannot be adequately notated. It is an expressive device that must be applied with the greatest artistry. This is clear both from the theoretical ources and from the music itself; it is a testimony to the subtlety of the French style. Bacilly writes: "Although I say that alternate dots are implicit in division, that is to say that of two notes, one is commonly dotted), it has beenthought proper not to mark them for fear of getting used to performing them by jerks"

APPLYING THESE IDEAS TO YOUR OWN PLAYING IN ANY MUSICAL STYLE

Whatever your views about correct way to play Notes inégales, the ideas can be refreshing if you've been brought up on the notion that "perfect musical time" is in some way, precise and repeatable like a metronome, also great things to explore in your own rhythms!

When it works well, the basic feeling is one of continuous refreshment and surprise and enjoyment as you play, in every single note you play, it's like a new thing, newly minted, born for the first time in this moment. This is felt by both performer and listener.

Get it wrong though and the music limps and drags and is just confusing to listen to. You need to feel the music and the surprise in every note, and then the unevenness of the Entasis comes through from that, if you try instead to play in a random unpredictable way just for the sake of it - that's when it goes wrong. It's a fine balance. However, many musicians, have this naturally, without thought, like breathing. Perhaps you have this, in your playing, already . As you work on your rhythmic precision, then you need to take care to continue to encourage this side of your playing as well, that's why I've given it as much space or more as the section on metronome practice.

Here are a couple of videos showing these ideas. I think you'll agree the timing and rhythm is wonderful, easy and enjoyable to listen to - and yet not based on strict repeating pulses like much of modern music. Indeed it's quite "fractal" in its rhythm, guestures within guestures.

Largo and Allegro in F minor by Hagen, performed by Robert Barto on Baroque Lute

And this one, where you hear the independence of the lines, using the technique of Vacillaire where the various parts are almost never synchronized exactly with each other

J. S. Bach: Sinfonia in g BWV 797, Robert Hill, fortepiano

More about it, from the same article as before:

"Entasis is an ancient Greek term meaning tensioning. Speech that is delivered in a metrically perfect manner has the power to cause the listener's brain to shutdown and cease processing the meaning of what is being said...all within a few seconds of hearing such speech. The human brain needs the condition of constant or stable irregularity to remain alert and attentive. Regularity eliminates the feeling of discomfort which chaos, the erratic and irregular, often creates. The balance in tension between the feeling of predictability, which constancy (stability) provides, and the feeling of anticipation, which irregularity and unpredictability creates, is a state of entasis. (The opposite of entasis is stasis or staticness.) In normal human speech, Entasis is brought about by the flow of thought, and this flow is both irregular and constant. So it must be in music.

The French, in the 17th and 18th centuries, understood the importance of entasis; musicians who wrote about inégal were likely referring to this concept. The word actually means rough, irregular, unequal, but the conventional interpretation of the word betrays the real meaning by forcing it to conform to the present fashion for perfect metricallity in performance practice of old music. That interpretation suggests that inégal means perfectly regular “limping.” Had the French writers meant that they might have used the term for limping or the phrase égal inégal

...

Metrical exactitude in musical performance also guarantees that most music is only heard but not listened to. It is the embodiment of slavishness in music, i.e. the music is the slave of the beat when it should be its master, exactly the opposite of what C.P.E. Bach suggested when he wrote that one should "endeavor to avoid everything mechanical and slavish. Play from the soul, not like a trained bird."[6]

This technique is especially challenging in its application, because musicians today are so rigidly trained in metrical regularity. Yet, like the beating of the heart, the musical pulse needs to fluctuate in speed as the emotional content of the music fluctuates. Like the natural shifting accents in speech, musical accents need to shift according to the meaning being expressed. To feel perfect, music must be metrically imperfect.."

You can find many more videos and sound recordings on their website, Craft of Musical Communication

TO USE A METRONOME OR NOT?

As someone who has spent many years of his life programming a software metronome, you might find it surprising to hear me say this. But - I've no interest at all in getting more musicians to use metronomes.

It's a bit like someone who designs drafting tools - doesn't mean you think artists should use them for their paintings. They are just tools for those who need them.

My aim with Bounce Metronome is just to help those who use one already or feel they might need one for whatever reason..

You can use a metronome to help with sensitivity to timing, and rhythmic precision, and sense of tempo and steady tempo - and you don't need to ever play the metronome with actual music to do that.

You can do that just with tapping and rhythm exercises along with the metronome, as well as rhythm exercises that don't use a metronome. Or, as some musicians do, use it with your music occasionally, e.g. to help deal with glitches and such like, for particular passages and so forth.

Many musicians do use a metronome, and they find it helpful for rhythmic precision. However, you don't need a metronome to have a wonderful sense of rhythm.

Many musical cultures with a great sense of rhythm never use the metronome at all!

WIKIPEDIA CONTENT IN THIS ARTICLE RELEASED UNDER CC BY SA

The material here from wikipedia articles Metronome and Notes inégales is originally written for wikipedia and so is released under the CC By SA license In short, anyone can use it as you like, including commercially, but must credit me as the main author, and any modifications you make must be released under the same license. So the same license also applies to those sections of this article.

Others contributed minor edits such as formatting, spelling, and rephrasing. You are not required to credit them.

BOOKS, AND ONLINE RESOURCES

Try Mac Santiago's "Beyond the metronome"

Also, Andrew Lewis's Rhythm, What it is and how to improve your sense of it especially his book 2 How to improve your sense of rhythm

They have numerous fun exercises and ideas to help with precise sense of time and rhythm. They complement each other, I recommend you get both if you can.

You can read Frederick Franz's Metronome Technique online for free, try especially his Chapter 2.His history section is an interesting read too.

Many other resources on my Metronome Links - Bounce Metronome page

If you are on Windows or Linux you can use my Bounce Metronome program to help Check Out the Astonishing Bounce Metronome Pro

KICKSTARTER FOR MAC

I've just launched a kickstarter to get it running on the Mac as well. I thought it was a good time to write a few articles on music that I'd been meaning to write for a long time.

Do support it if interested to see this program on a Mac:

Here is the kickstarter page if you want to support it: Bounce Metronome, Tune Smithy, Lissajous 3D... on Intel Mac!

You get an unlock key for all my programs if the project succeeds.

VIDEO RESOURCES

You can also watch many videos on my Video Resources pages and youtube channel, this is the page about the Go Silent Briefly exercises

How Steady is Your Tempo? - Test With Go Silent Briefly

ANY SUGGESTIONS, IDEAS, ... DO COMMENT

Do you have any links ot interesting books on use of a metronome, or developing a great sense of rhythm. Or any ideas you've come across that you like to mention, tips and so forth. Or questions about any of this?

Do comment in the space below.

Comments