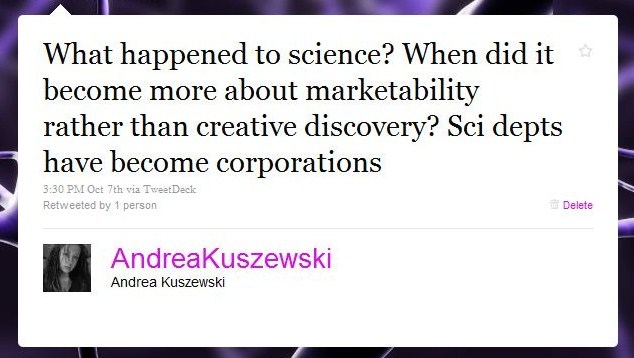

A week or so ago on Twitter, I tweeted this:

Based on some of the responses I got, I decided to probe a little further. I wanted to see if I was in the minority in my opinion, or if others felt the same way. Apparently, I'm not alone.

The way we approached science about 30 or 40 years ago is vastly different than how we do today. I'm not talking about the obvious differences due to technology, either. Indeed, with the advances we've made in technology, we have opportunities for rapid and monumental discovery more now than we ever have at any point in history. So with these amazing modern research tools at our disposal, are we making the most progress possible in creative scientific discovery?

I don't think we are. And here's why: Creativity is no longer encouraged in science.

Sure, incremental creativity, such as replication or moving a field forward in a direction it's already going, is encouraged and expected. But I'm talking about paradigm-shifting and redirective types of creative output; the kinds of ideas that completely change the trajectory of a field, knocking the science world on its rear end, as Einstein, Feynman, and other pioneers in creative scientific research did. You just don't see that kind of risk-taking with scientific ideas anymore, and if you do, it's headline-worthy, and very infrequent.

So when and why did this big shift in scientific mindset occur?

One big one reason: Money. I can't state this any more eloquently than Physicist Hal Lewis did Friday, October 8th, in a resignation letter he submitted to the American Physical Society. As distressing as this move was for him, he decided that after sixty-seven years, leaving was his only option. Here is the beginning portion of his letter (you can link to the rest):

From: Hal Lewis, University of California, Santa BarbaraHe goes on to describe and list in detail, the specific grievances he has with the Society's behavior surrounding Climate-Gate and other allegedly dishonest acts that followed.

To: Curtis G. Callan, Jr., Princeton University, President of the American Physical Society

6 October 2010

"Dear Curt:

When I first joined the American Physical Society sixty-seven years ago it was a much smaller, much gentler, and as yet uncorrupted by the money flood (a threat against which Dwight Eisenhower warned a half-century ago).

Indeed, the choice of physics as a profession was then a guarantor of a life of poverty and abstinence - it was WWII that changed all that. The prospect of worldly gain drove few physicists. As recently as thirty-five years ago, when I chaired the first APS study of a contentious social/scientific issue, The Reactor Safety Study, though there were zealots aplenty on the outside, there was no hint of inordinate pressure on us as physicists. We were therefore able to produce what I believe was, and is, an honest appraisal of the situation at that time.

We were further enabled by the presence of an oversight committee consisting of Pief Panofsky, Vicki Weisskopf, and Hans Bethe, all towering physicists beyond reproach. I was proud of what we did in a charged atmosphere. In the end, the oversight committee, in its report to the APS President, noted the complete independence in which we did the job, and predicted that the report would be attacked from both sides. What greater tribute could there be?

How different it is now. The giants no longer walk the earth, and the money flood has become the raison d' etre of much physics research, the vital sustenance of much more, and it provides the support for untold numbers of professional jobs. For reasons that will soon become clear, my former pride at being an APS Fellow all these years has been turned into shame, and I am forced, with no pleasure at all, to offer you my resignation from the Society..."

(Those details, while very relevant, to his circumstance in particular, are not necessary to discuss here in order to get a general picture of what happened to the field of science.)

He goes on to say:

"...Some have held that the physicists of today are not as smart as they used to be, but I don't think that is an issue. I think it is the money, exactly what Eisenhower warned about a half-century ago. There are indeed trillions of dollars involved, to say nothing of the fame and glory (and frequent trips to exotic islands) that go with being a member of the club.I am too young to remember a time when it was any different than it is now, but I know plenty of people who were working towards their degrees in the Universities before the 1980s; it was truly a different time for research. It used to be enough that a scientist had an interesting concept to study, a problem that was intriguing, a new idea that had never been explored. But maybe I have an over-romanticized view of what research should be—seeking knowledge for knowledge's sake.

Your own Physics Department (of which you are chairman) would lose millions a year if the global warming bubble burst. When Penn State absolved Mike Mann of wrongdoing, and the University of East Anglia did the same for Phil Jones, they cannot have been unaware of the financial penalty for doing otherwise. As the old saying goes, you don't have to be a weatherman to know which way the wind is blowing. Since I am no philosopher, I'm not going to explore at just which point enlightened self-interest crosses the line into corruption, but a careful reading of the ClimateGate releases makes it clear that this is not an academic question..."

It isn't like that any more. Now science is a business, one that has a market to feed, and those ideas which have no monetary market value are not ideas that we are encouraged to explore. Departments are funded by grants, grants which count on publications, publications that are printed in journals, which the public then purchases. This model worked for a while. But not any more.

With the rise of the internet as a scientific tool, we are seeing this research/publishing model breaking down more and more every day. This old model didn't count on the lightning fast flow of information that is freely shared over the web, getting around the journal paywalls. Social media has become the Napster of academic articles; all it takes is a tweet, requesting a copy of an article, and it's delivered to your inbox in mere minutes. Some may say it's wrong to do this, but I say it's wrong to be restricted from using data in research just because you can't afford to buy it. Obviously the journals can't be making money this way, so why are we still pushing this model of research and publication?

Universities still need to worry about how many publications they can crank out in one year, so that they can secure their funding for the years to come. This type of situation seems a bit icky to me, and creates an environment that lends itself to desperation and dishonesty, as scientists feel the pressure to produce—it becomes more about quantity than quality. When that becomes more commonplace, so do things like this, where post-docs are sabotaging grad student experiments, afraid of falling behind in the race to publish, afraid of losing their jobs.

When we are under such constant pressure to churn out a product, our creativity suffers. I've talked about this before a number of times. And since we need creativity in order to advance science, this whole pressure model of research and publication seems counter-productive to what we really want. So the question becomes: Is scientific discovery suffering?

Why not investigate the effect of this publishing model on scientific output?

Well, it has been investigated, in a way. After I sent that initial tweet, someone posted this article: Universities Are Trying Too Hard To Cash In On Discoveries, Says Academic Panel. Apparently, the introduction of patents and funding in exchange for scientific data following the 1980 Bayh-Dole Act has been a concern, so the National Academies decided to conduct an investigation. This is what the panels concluded:

The Bayh-Dole legal framework and the practices of universities have not seriously undermined academic norms of uninhibited inquiry, open communication, or faculty advancement based on scholarly merit. There is little evidence that IP [Intellectual Property] considerations interfere with other important avenues of transferring research results to development and commercial use.Hmm. Well, I'd hate to come out and say I don't buy it, but I just don't buy it. Here's the main reason why:

They collected their data in part by interviewing current employees and faculty members of institutions.

This may seem to make perfect sense—if you want to know if employees are satisfied, feel like they are under pressure, or feel as if they have creative constraints, just ask them right? WRONG.

There's this thing in social psychology we call Cognitive Dissonance. Specifically, the Effort-Justification Paradigm. This states:

"Dissonance is aroused whenever individuals voluntarily engage in an unpleasant activity to achieve some desired goal. Dissonance can be reduced by exaggerating the desirability of the goal. Aronson&Mills had individuals undergo a severe or mild "initiation" in order to become a member of a group. In the severe-initiation condition, the individuals engaged in an embarrassing activity. The group turned out to be very dull and boring. The individuals in the severe-initiation condition evaluated the group as more interesting than the individuals in the mild-initiation condition."

You can imagine that the stress, competition for a limited number of positions, the low pay, and the pressure to produce could be considered a "severe-initiation" condition. The point here is this: We can't just go on self-report from practicing academics, who have already been through the gauntlet to get where they are, and ask them how happy, fulfilled, and satisfied they are with their jobs. Even if they are unhappy, underpaid, and being creatively stifled, they are more likely to claim things are perfectly fine, just due to cognitive dissonance.

How do you remedy this conundrum? I don't know—maybe interview people who have left academia for these reasons? In addition, perhaps they can talk to undergrads who are preparing for graduate study to get a feel for the expectations of potential candidates. Once you manage to secure your little spot in a department, either as a grad student, post-doc, or faculty member, chances are you're not going to do something to screw it up, like go on record in front of a committee and complain about how crappy life is in your department.

What is the solution? Is there one?

Honestly, I don't know what the exact solution is; I'm not saying I have all the answers here. But we need to stop kidding ourselves and pretending that the current model is working, because it isn't. Scientists aren't happy, journals are losing money, the public is in a state of discontent, magazines are folding, newspapers are in financial crises, Climate-Gate, Pepsi-Gate, ad nauseam, ad infinitum. So why are we still shoving this old model down our throats? Do we have a codependent relationship with the current state of affairs? Are we too afraid to take risks? If that's the case, no wonder we face a creativity crisis in America.

We need to understand that we are living in a different world now. This is a digital age. We have different medium to work with. Paper journals, and waiting 6 months to a year for a peer-reviewed article to reach the public is unacceptable. Being required to pay to view scientific data is unacceptable. We need to find a new model for research, publication, and data sharing.

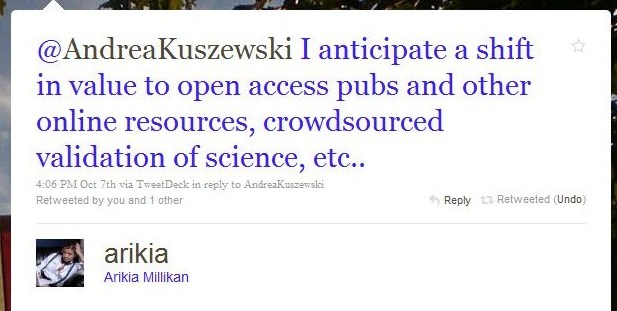

A comment by Arikia Millikan during this discussion pretty much sums up my thoughts on the subject as well:

She's absolutely correct. Collaboration, open source data, and new types of 'peer review' that includes some type of crowdsourcing, is where we need to be headed. Open Access journals, such as PLoS One should be the standard, not the exception, for data sharing. There are some valiant attempts being made right now at adjusting to a new model of scientific research, specifically the addition of blogging platforms to increase science communication, but this isn't enough, and too many of them are falling short of fully embracing a digital, open-sharing network model. Much of what I see is the same old paper model being squeezed into a digital platform; we need to scrap the old model altogether and come up with something completely different in order for it to work.

What are our options? Radical openness, for one. I mean REAL openness, inviting everyone in, not just a select few. I know, there will be validity issues to be addressed. Challenging? You betcha. But that shouldn't stop it.

I know we can do this—we all just need to work together and embrace true collaboration. There is too much secretive hoarding of ideas, paranoia of being "scooped", and competition in the race to publish. We can solve so many more of the world's problems through collaboration— ideas sparking off each other, shining insight and gaining perspective in ways that are only possible when we pool our minds together. We need to put scientific discovery ahead of prestige and money if we are ever to break out of this information and creativity crisis. I know the brain power is there—let's give it a platform in which to emerge, grow, and flourish.

Myself and Arikia on Twitter.

Comments