Older now, I can drink a beer socially and I sometimes drink a glass of red wine because the consensus says it is good for you in moderation, but I am still not really a drinker.

However, I love to learn about drinking. I have giant tomes on wine, whole books on Scotch, I have a 2008 4-pack of Bourbon County in my garage 'beer fridge' (yes, I have a beer refrigerator in the garage that holds almost everything but beer) that I am waiting to crack open because it supposedly 'ages' up to 5 years. Beer that ages like wine. I am a sucker for that.

You can imagine how excited I was getting a copy of "Foam" by UC Davis professor Charles W. Bamforth, courtesy of the American Society of Brewing Chemists. This is volume one - of six - about beer. That means it will essentially be the beer equivalent of William Shirer's "The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich", except it has no Nazis. And it is about beer. Okay, maybe that was not the best comparison but people who have read that book know what I am talking about. It is everything you could ever want to know. And so it is with "Foam". This is basically the best beer foam user manual you are going to get. Like all good user manuals, it even has a Troubeshooting Guide.

Want to learn about beer foam without going to school for 8 years? FOAM is for you.

Some book about whacking Osama bin Laden (and, less likely, a book called Science Left Behind) is going to be a bestseller in September but this should be instead. What do people care more about, a dead terrorist or beer? Exactly. Professor Bamforth can't be thrilled I have invoked Nazis and terrorists in a review of his book but that is how culturally significant I think beer - and therefore beer foam - is.

You see, I have always felt like beer foam is underrated. It turns out I am not alone and Bamforth's book covers the gamut of the field - from psychology to physics to chemistry and engineering.

First, some psychology. Part of enjoying anything, be it beer or a restaurant or awesome science sites, is presentation. My wife is a terrific cook but it will not taste as good if my sons are fighting over who gets to marry that girl on the iCarly TV show, while a cozy winter lodge and a fireplace while someone else watches our children fight over Miranda Cosgrove makes even canned chili appealing.

Part of enjoying beer is the visual aspect. Social psychologists will say beer evolved to match what people like while evolutionary psychologists will say we evolved to like the beer that gets us a date. Social psychologists win this one because women, that evolutionary target of men, who are the primary drinkers, don't play by the rules regarding beer foam they should play by if biology were the issue.

Beer foam: The Gender Gap

Does beer foam need some sort of outreach program? Are women biased against it?

Maybe. It might explain why men drink more beer. Beer is a total package, it has an aesthetic and a taste but color and foam are the most striking things people first notice in beer. What foam is left over on the glass after the beer, the 'lacing' as experts call it, impacts the perception also. As I said, beer evolved to match what people like - because people buy what they like, not what is available, over the long haul - and people seem to like 'the middle' when it comes to foam; not too much and not too little or else it gives them ideas about its quality and even its alcohol content. But not all people. While all people had a preference for how 'clean' they like the glass to be when finished (and therefore how much lacing) there was a real gender difference in how much lacing women wanted.

Conclusion: It may be that the market for lace in beer, much like in a Victoria's Secret, is not women at all.

Are the Scottish anti-science about beer foam?

Sure, the northern Europeans are most famous for beer but Scottish people drink too. Celtic fans need to do something while waiting for the match to be over so they can headbutt Rangers fans and then kick them when they are on the ground, and whisky is too expensive to drink for two hours.

The science is settled, the consensus is clear; foam matters, it is a harbinger of beer to come. Yet not everyone accepts its importance. The wrong foam was perceived by Americans as being lower quality and even less alcoholic. They also felt like more foam meant it came from a dirtier glass. That last part is incorrect but Americans were at least thinking about the foam. The Scottish cared about foam the least of all countries tested.

Conclusion: the Scottish are anti-science about beer foam. At least they got haggis right.

The Physics and Chemistry of Beer Foam

I can't go into too much detail here because we are talking about a 60 page book on beer foam in which not a single paragraph is wasted. I would have to write 120 pages to cover everything. You should obviously just buy the book if you want to know the true nuts and bolts of foam.

I can tell you that, were it legal, beer foam would be a great way to teach high school students about science. There is a science reason 1,500,000 bubbles in the foam of a glass of beer play so nicely and that reason is surface tension and surface-active molecules. The nucleation we have come to know and love about beer foam is a vital aspect so by all means get annoyed if a bartender or waiter thinks he is doing you a favor gently pouring your brew down the side of a glass. He is cheating both you and science. Bamforth cleverly relates viscosity in beer to baseball fans in Wrigley Field, a metaphor you can appreciate if you like teams that cannot win Big Games.

These beer guys know applied chemistry in a way that is dizzying so they do what they can to mitigate anti-science waiters pouring beer down the side of the glass. That means foam-stabilizing materials and terms like proteolysis. Trust me, they care about foam so you don't have to.

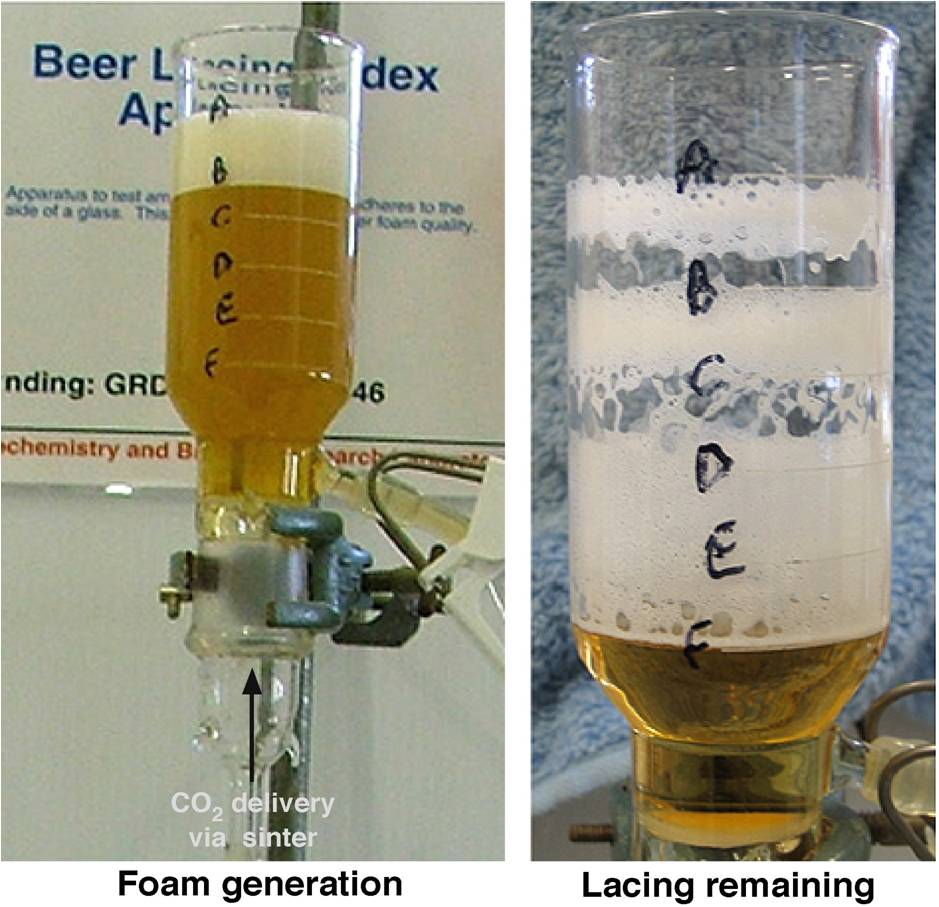

And they get cool equipment.

The equipment used in their beer lacing index. Credit: Dr. Evan Evans

How to get the best foam

If you are a serious beer foam person - and I am after reading this book, even if for no other reason than to annoy my friends - and making your own beer, you can get a lot of benefit out of his Troubleshooting Guide in Chapter 7. Yes, this really is a beer foam user's manual.

Otherwise, you likely just want to optimize the foam of the beer you just got. Here are some handy tips:

1) Consider a foam-nucleating glass. They mention Headmaster and Head Keeper as go-to trade names. I have one on my birthday list!

2) Watch your detergent. A beer, therefore including the foam, has already been optimized in regards to lipids (fats) so adding your own is not a great idea. Combining the many polypeptides and peptides in beer with external lipids in detergents means lousy foam in your beer because detergent is designed to make its own foam. Whether you can see it or not, a fat-based detergent will leave a film on the glass, which means duds for suds and beer will go flatter faster.

3) Don't use your beer glass for anything else. Do you use your coffee mug for soup? Of course not. Same with beer. And don't dry it with a towel either.

The beer used in my field testing:

Image: Hank Campbell

I told Drs. Bamforth and Evans I wanted to crack open one of those 2008 Bourbon County's from paragraph one to write this article but that is an 'event' beer and it needs to have more people over. Impossible on a Friday morning in Folsom - Intel people won't start drinking until 2 PM. So an update on that will have to come later.

More reading:

Evans, D.E., and Bamforth, C.W. (2009) Beer foam: achieving a suitable head, in “Handbook of alcoholic beverages: Beer, a quality perspective” edited by Bamforth, C.W., Russell, I., and Stewart, G.G., Elsevier Burlington MA, pp 1-60

Evans, D.E., and Newman, R. (2009) Its better in a glass! The Brewer and Distiller International 5(10): 26-29.

Comments