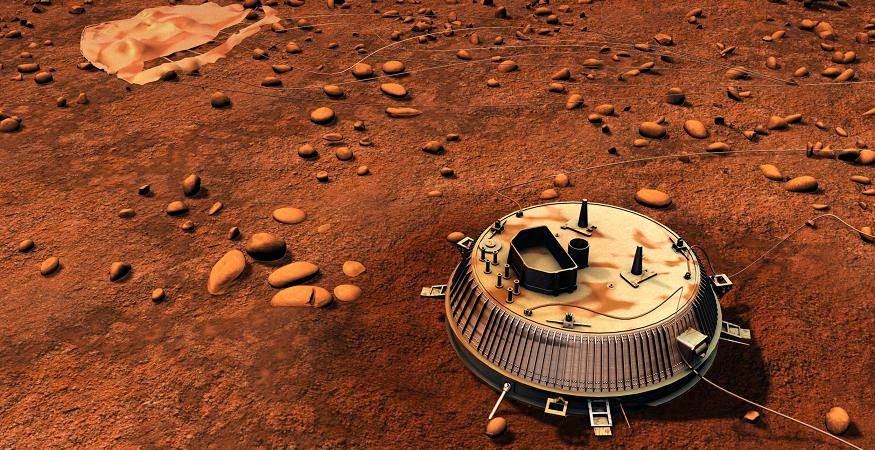

Ten years ago, on Jan. 14, 2005, some orange-y image, showing an alien scenery with lots of pebbles in the horizon, was at the center of ESA scientists’ attention.

The snapshot of a distant world’s landscape was truly amazing. It was Saturn’s moon Titan with an orange surface seen through the lens of ESA’s Huygens lander, an exciting one-of-a-kind experience for European scientists as they can proudly say:

“We’ve landed there!” And “there” means the outer solar system where no probe has ever landed before. ESA scientist Claudio Sollazzo, who was the Mission Operations Manager in the Huygens team, recollects this demanding and challenging historic effort, which was also a joyful experience. "I was like a small kid, full of excitement and wonder, when I saw the first image of Titan's surface," Sollazzo told me. "Indeed the results have been fantastic."

The snapshot of a distant world’s landscape was truly amazing. It was Saturn’s moon Titan with an orange surface seen through the lens of ESA’s Huygens lander, an exciting one-of-a-kind experience for European scientists as they can proudly say:

“We’ve landed there!” And “there” means the outer solar system where no probe has ever landed before. ESA scientist Claudio Sollazzo, who was the Mission Operations Manager in the Huygens team, recollects this demanding and challenging historic effort, which was also a joyful experience. "I was like a small kid, full of excitement and wonder, when I saw the first image of Titan's surface," Sollazzo told me. "Indeed the results have been fantastic."

The Huygens probe was delivered to Titan by NASA's Cassini spacecraft after a dormant interplanetary journey of 6.7 years - although Huygens was activated every six months for health checks.

"As the Mission Operations Manager of the Huygens mission, I certainly was very concentrated on the technical aspects of the endeavour, but I can still remember the joy and great sense of relief when I saw the first significant telemetry data from Huygens." Sollazzo said. "I also was quite intrigued by what we would find: of course there was still a few hours from the viewing of the first images, but I still remember imagining myself 'riding' the probe during the descent and looking at the fantastic landscape around. Of course, it was a bit of day-dreaming but the moment was so tense and we could do nothing else but wait..."

Huygens separated from the NASA Cassini orbiter on December 25, 2004. The probe started its descent through Titan's hazy cloud layers from an altitude of about 1270 km. During the following three minutes Huygens had to decelerate from 18 000 to 1400 km per hour. A sequence of parachutes then slowed it down to less than 300 km per hour. At a height of about 160 km the probe's scientific instruments were exposed to Titan's atmosphere, and at about 120 km the main parachute was replaced by a smaller one to complete the 2.25-hour descent.

Miguel Pérez Ayúcar, ESA's Science Operations Engineer in the Huygens team, was working to ensure that the Huygens probe delivers as much data as possible from its intense two-and-a-half-hour ride through Titan's atmosphere. “It was one of the best moments of my life,” Ayúcar told astrowatch.net. “I was at the Main Control Room at the European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) in Darmstadt, Germany, and I was monitoring the consoles with the radio link. The first indication came from the big Earth radio-telescopes that were directly listening to the Huygens carrier. Signal was there!”

Since Huygens was too small to transmit directly to Earth, it was designed to transmit the telemetry data obtained while descending through Titan's atmosphere to Cassini by radio, which would in turn relay it to Earth using its large 4-meter diameter main antenna.

“Just a peak line on the power spectra, but so important. We could confirm that the first part of the entry had been successful, the heat shield had worked, we had a safe entry into Titan's atmosphere, and we had a stable radio link. Very promising!” he said. “Already a technological success, but we needed now the science success. For that we had to wait some hours until Cassini would finish the Huygens relay phase, point back to Earth and dump the precious data.”

"When the first data arrived, all the technical problems come to us and we had to resolve them. So immediately I went back into my role and made sure that the scientists got their exciting data." Sollazzo said.

"As the Mission Operations Manager of the Huygens mission, I certainly was very concentrated on the technical aspects of the endeavour, but I can still remember the joy and great sense of relief when I saw the first significant telemetry data from Huygens." Sollazzo said. "I also was quite intrigued by what we would find: of course there was still a few hours from the viewing of the first images, but I still remember imagining myself 'riding' the probe during the descent and looking at the fantastic landscape around. Of course, it was a bit of day-dreaming but the moment was so tense and we could do nothing else but wait..."

Huygens separated from the NASA Cassini orbiter on December 25, 2004. The probe started its descent through Titan's hazy cloud layers from an altitude of about 1270 km. During the following three minutes Huygens had to decelerate from 18 000 to 1400 km per hour. A sequence of parachutes then slowed it down to less than 300 km per hour. At a height of about 160 km the probe's scientific instruments were exposed to Titan's atmosphere, and at about 120 km the main parachute was replaced by a smaller one to complete the 2.25-hour descent.

Miguel Pérez Ayúcar, ESA's Science Operations Engineer in the Huygens team, was working to ensure that the Huygens probe delivers as much data as possible from its intense two-and-a-half-hour ride through Titan's atmosphere. “It was one of the best moments of my life,” Ayúcar told astrowatch.net. “I was at the Main Control Room at the European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) in Darmstadt, Germany, and I was monitoring the consoles with the radio link. The first indication came from the big Earth radio-telescopes that were directly listening to the Huygens carrier. Signal was there!”

Since Huygens was too small to transmit directly to Earth, it was designed to transmit the telemetry data obtained while descending through Titan's atmosphere to Cassini by radio, which would in turn relay it to Earth using its large 4-meter diameter main antenna.

“Just a peak line on the power spectra, but so important. We could confirm that the first part of the entry had been successful, the heat shield had worked, we had a safe entry into Titan's atmosphere, and we had a stable radio link. Very promising!” he said. “Already a technological success, but we needed now the science success. For that we had to wait some hours until Cassini would finish the Huygens relay phase, point back to Earth and dump the precious data.”

"When the first data arrived, all the technical problems come to us and we had to resolve them. So immediately I went back into my role and made sure that the scientists got their exciting data." Sollazzo said.

“The data was being relayed back to Earth via Cassini High Gain Antenna (HGA). Actually the downlink rate was higher than the actual descent transmission from Huygens to Cassini, so we were seeing a 'fast forward'. Everybody was anxious about the data,” Ayúcar noticed.

The probe was designed to gather data for a few hours in the atmosphere, and possibly a short time at the surface. It continued to send data for about 72 minutes after touchdown and then its batteries died.

“I was involved myself in the analysis of the engineering data. I am an engineer, so I was not directly involved in any experiment. But still the probe housekeeping data can give you so much extra information! Using the radio link telemetries we could understand the attitude and spin of the probe in the whole descent, the touchdown phase and surface orientation, and how the link interacted with the surface at grazing angles before Cassini disappeared below the local horizon,” Ayúcar revealed. “I had the honor to be invited into the DISR [Descent Imager and Spectral Radiometer] restricted area at ESOC, as the telemetry stream with the images was being decoded. Many people were crammed on the computers. Some of the images triplets were smoggy, not much to see at first glance. But then bang! The images of the dark channels over the kind of bright shoreline. It was breathtaking.”

Early imaging of Titan from the Cassini mission was consistent with the presence of large bodies of liquid on the surface. The photos showed what appeared to be large drainage channels crossing the lighter colored mainland into a dark sea. Some of the photos suggested islands and mist shrouded coastline. On Jan. 18, 2005 it was reported that Huygens landed in "Titanian mud". Mission scientists also reported a first "descent profile", which describes the trajectory the probe took during its descent.

“When the famous landing orangy image with the small ice pebbles and the 'titanscape' and horizon line was displayed in the ESOC MCR [Main Control Room] windows to the world, I could only think, very moved, that it was a step forward in human history. And we were part of it,” Ayúcar said. “The other mission comparable in reaching the people, that has taken so much attention not only on the scientific circles but on the society, is Rosetta and Philae. These are the types of missions that make equally scientists and regular people dream.”

This unique result complements the data taken by the Descent Imager and Spectral Radiometer (DISR) instrument. When Huygens came to rest on the surface of Titan, DISR was pointing due south. Its images show stones and terrain in good agreement with the newly deduced western facing radio data.

Sollazzo is convinced that Huygens landing on Titan is the greatest European achievement ever in space exploration: "I am a bit biased and believe that the Huygens landing was the greatest European achievement in space exploration. I cannot deny that the Rosetta mission and the landing of Philae on the comet is a fantastic achievement, but Huygens was the first, and farthest away from Earth landing, and in my personal listing, indeed the greatest achievement."

Sollazzo is convinced that Huygens landing on Titan is the greatest European achievement ever in space exploration: "I am a bit biased and believe that the Huygens landing was the greatest European achievement in space exploration. I cannot deny that the Rosetta mission and the landing of Philae on the comet is a fantastic achievement, but Huygens was the first, and farthest away from Earth landing, and in my personal listing, indeed the greatest achievement."

Cassini-Huygens is a joint NASA/ESA/Italian Space Agency (ASI) mission. NASA’s Cassini spacecraft continues to orbit Saturn, making an extensive survey of the ringed planet and its moons.

Comments