It's easy to dismiss Dr. Atkins. His books are self-promoting (he named the diet, which pre-existed him by 150 years, after himself) and full of hyperbole:

"Atkins is the most successful weight loss - and weight maintenance - program of the last quarter of the twentieth century. The fact is, by methods you're about to learn, it works an astonishing proportion of the time for the vast majority of men and women." -from Dr. Atkins' New Diet Revolution.

He frequently referenced the medical literature obliquely, or added references after bold pronouncements that correspond to papers that don't actually support his point. He invented words like vitanutrients. He published weight loss books with his name in bold letters, but no peer-reviewed studies of his outcomes. He made sweeping generalizations about the effects of dietary choices without any real attempt to validate his ideas using the scientific rigor necessary to publish in journals. His books sometimes get the science just plain wrong, such as when he contends that insulin is a glucose transporter. He was wrong about a lot of things, but as a friend of mine used to apply to me, "even a blind squirrel occasionally finds a nut." We shouldn't confuse the objections we have with Dr. Atkins's style, or even his reasoning, with objections to his advice. We should look at his proposition, if we can, without bias.

The components of the carbohydrate hypothesis are:

Carbohydrates (sugar, breads, pastas, fruit, soda) raise insulin levels

Insulin's job is to move sugar and fat out of the blood

It does this mainly by opening up fat cells for storage

It also decreases fat break down

Increased insulin means increased storage and less fat burning

Therefore-

High sugar causes high insulin, causes fat storage and obesity.

This mechanism is, in fact, an accurate description of how energy gets shuttled into cells. But to show that sugar and other carbs uniquely fatten us, we need to consider whether the system above, which operates in lean individuals as well, has somehow been driven to excess by our changing diet.

To critically review what macronutrient choice does for our struggle with obesity, we can do no better than discuss the work of Gary Taubes. I know many doctors who disagree with what Gary Taubes has concluded about obesity, but none who have actually read his book. To finish Good Calories, Bad Calories (his encyclopedic history of the low fat diet hypothesis and why it is false - more aptly titled for the UK printing as The Diet Delusion) is to be convinced that we have been pre-ordained to become heavier by the bad advice that has come to us from the USDA and the American Heart Association. He makes the best case I've seen that we are fat because we eat too many carbohydrates. The book walks us through the history of low-fat dieting, how the common wisdom that eating fat causes weight gain became the common wisdom and why it has inadvertently backfired. He provides exhaustive evidence to back up his story: he documents hundreds of interviews with the scientists who have written the guidelines and position statements that steer our judgments of what constitutes a healthy diet. He also lays out the findings of hundreds of peer-reviewed research trials and analyses that lead directly his conclusion that Dr. Atkins actually stumbled across the truth. Taubes shows that the low-fat advice that has dominated the popular awareness for the last 40 years was an accident of which experts happened to be in power in research circles at a certain period of our history.

That some of our best scientists believed that a low-fat diet would give us better longevity is without question. But those scientists, Taubes argues, quite convincingly, were simply wrong. In addition, they were frequently misunderstood, misquoted and used to push an agenda. They had some decent, but incomplete, evidence about the causes of heart disease that was taken as gospel by government agencies and medical reporters that needed something clear to tell the public. The best way to eat to avoid heart disease was taken as the best way to eat, period. In reality, the evidence was never even clear regarding fat and heart disease. The data had nuances that couldn’t be fit into a headline and two generations of us gained a lot of weight trying to avoid getting fat by avoiding eating fat. As evidence grew that avoiding fat was not a cure for obesity or heart disease, the message went unheard, because it was inconvenient and hard to understand. In fact, though, eating fat doesn't make you fat any more than eating cholesterol gives you high cholesterol, or eating salt gives you a high salt level in the blood (or high blood pressure, for most of us). These points are all evaluated and dismissed in the book. But more importantly, Taubes presents a the case that the heart-focussed eating that prevailed from 1970 to 2000, had an unexpected side effect: the obesity epidemic.

The argument in Good Calories, Bad Calories is simple: because we were told to avoid high-fat foods, we looked for labels and products that claimed to be “low-fat.” The packaged food industry, in order to produce the highly enjoyable taste experience we’ve come to expect from anything that comes in a wrapper, had to replace the fat with something we’d enjoy. That something was carbohydrates, the complex kind and the simple kind, such as sucrose and fructose. Coming at a time when we finally had enough disposable income to eat pre-packaged food every day of the week, we essentially snacked, drove-through and micro-waved ourselves into our current state of obesity, by letting the food companies feed us tasty carbohydrate treats.

None of this is hard to believe and really wouldn’t bother most doctors. What’s more challenging to accept is Taubes's argument that calories simply don’t matter when it comes to weight gain. They of course, mediate the process, but excess consumption per se, is only accident of too much carbohydrate. No weight gain is possible if one avoids carbohydrate and weight gain is nearly inevitable if one indulges in much carbohydrate. Sugars and carbs are viewed as essential to the process, or even considered almost a "toxin" when it comes to our metabolism.

His other controversial stance is that fat doesn’t matter. It doesn’t cause obesity and in fact, eating it (at least the right kinds) will help you avoid a heart attack while losing weight. Does this make any sense? The evidence is mounting in his favor. Taubes is certainly right that we need to remember that the body isn’t an empty set of tubes and circuits that utilizes fuels only in the forms they are ingested. The human organism is a complex array of chemical reactions, hormonal signaling, energy balancing and nutrient sensing that acts on the cellular and molecular level to produce health. We don’t eat fat and get fat. We don’t eat cholesterol and have high cholesterol, the levels of these entities in our bodies is highly regulated. We are all exposed to a diet with more fat and cholesterol than needed, but some of us don't handle the excess well. All of these processes are regulated by hosts of genes and hormones that have evolved over millennia, perhaps demonstrating that we've been through these fluctuations before. Lately, the regulation of our weight seems to be off-kilter, causing a, perhaps, unprecedented weight gain in many populations. The question for the moment is how much of the regulation of weight gain is driven by carbohydrate in the diet?

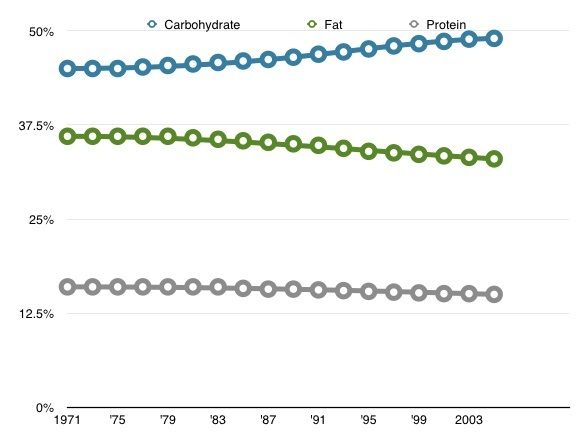

The carbohydrate hypothesis rests on on the assertion that we are currently eating more carbohydrate than we were a few decades ago. If we were not eating more carbs than previous, we could throw out the hypothesis quite easily. But that is not the case. By various measures, including USDA numbers of what gets produced by the food industry and surveys of how people typically eat on a day to day basis (such as the large U.S. national survey, NHANES), it's been shown that we've had a reasonably large shift in our consumption patterns. In a paper looking at the percent of carbohydrates, fat and protein in the U.S. diet between the early 70’s and 2006, Austin, Ogden and Hill (AJCN 2009) report that carbohydrates, as a percentage of diet, have increased over those thirty years. This has happened while the percentage of protein and fat have decreased and the obesity rate in the country has tripled:

Since obesity rates have risen markedly in sync with the increase in carbohydrates and decrease in fat, the carbohydrate hypothesis argument holds that the USDA, your cardiologist and the well-meaning folks who make “low fat” sour cream potato chips have caused us to make a huge mistake: While avoiding fat for the last 30 years, we have substituted carbohydrates. Obesity and type 2 diabetes epidemics are the result. But do these data really support that view?

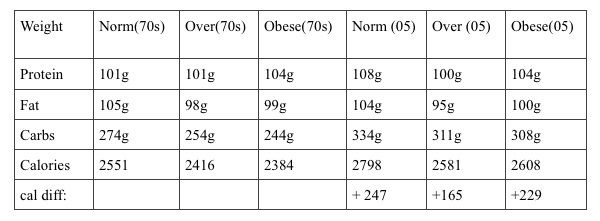

Looking at the numbers reported by Austin et. al. Between the periods 1971-75 and 2005-2006, everyone in the U.S. learned to eat more. Separated into groups considered normal weight, overweight and obese, the average person in each group ate about 200 more calories per day. Meanwhile, the percent of carbohydrate increased from 45% to 49% (other estimates are as high as 55%) while fat decreased 36% to 33% and protein decreased from 16% to 15% (with a little bit of rounding). So you could certainly choose to draw the conclusion, looking at the graph above, that American adults are susceptible to public health messaging and that they dutifully reduced their fat consumption during this 30 year period. That would be a mistake. When you take the reported data in the paper and convert the calorie percents to grams of each macronutrient (which the authors do discuss), you get the following:

What this demonstrates is that we are eating the same total quantity of protein and fat, by grams, as we’ve always eaten. The only thing that's changed between the seventies and now is that we've added, on average, 50 grams, or about 200 more calories worth, of carbs. Not substituted, but added. The entire increase in calories in our daily consumption over the last 30 years is due to carbohydrate. We haven’t heeded any public health advice about avoiding fat, we are eating all the fat we ever did, we've just increased carbs and calories on top of that.

Why are we all heavier? If these numbers are to be believed, the obese folks have increased their intake, on average, 229 cals per day. This would translate to 81,760 excess calories per year, which (if each pound of fat is produced by approximately 3500 excess cals consumed) would yield a weight gain of 23 pounds. That seems pretty close to the reported increase in weight of obese people over the last three decades, which is 18 pounds on average. The only problem is that the calories resulting in 23 pounds from these data would be per year. That’s right, if these numbers are accurate, the average obese person would have gained 700 pounds between the two NHANES surveys. Since normal weight respondents in the data-set report eating 247 cals more daily, they’d be 750 pounds heavier…

Here is where we run into the limits of using the 3500 calorie = a pound rule. As you get heavier, you expend and take in more calories to sustain your mass, so the increase becomes less excessive as a new equilibrium is found. Plugging the increase of 229 cals into the NIH bodyweight simulator, we find that the expected weight gain, depending upon starting assumptions, would be close to 20 pounds. That's quite a bit different from 750 pounds, nearly identical to the 18 pounds reported and demonstrates why calculus is needed in these discussions, rather than simple arithmetic.

Notice that this study confirms (by the self-report of many thousands of individuals) what Dr. Liebel measured in the study I discussed in a previous post, "The obese and control subjects required comparable caloric intakes." While the obese group reports an increase of 229 calories more over the three decades, the lean participants report eating 247 calories more, which is an indistinguishable difference, given the known difficulties in assessing caloric intake with precision. The lean and overweight also report eating the same macronutrient ratio as the obese, supporting the view that we are all exposed to the same food environment and eat roughly the same, but some of us are resistant to obesity.

Our increased obesity correlates to an increase in the amount of calories eaten, composed entirely of carbohydrate and this has happened during a period when carbohydrate has gradually increased as a percentage of diet. But does this mean that carbohydrate is somehow "bad" for us?The question remains, is it the carbs, or the calories they represent, that ultimately causes obesity?

If calories are the problem, diets of varying compositions should work equally well for weight reduction, as long as they reduce calories by the same number. If carbohydrates are somehow more "fattening" than the other macronutrients, reducing carbohydrates during weight loss should show signs of improving other internal regulatory factors, in addition to weight. J. Ebbeling and colleagues looked at this question by putting volunteers on equal calorie diets for three months. In a 2012 study reported in JAMA, the researchers followed 21 volunteers on variable carbohydrate diets and assessed their hormonal and metabolic responses. The question was whether there was a "metabolic advantage" of a low-carbohydrate diet, as argued by Atkins and many of professionals who see weight loss clients. After losing, on average, 12.5% of body weight over 12 weeks, the subjects were stabilized over a month to find the calorie amount each needed to maintain that loss. After the stabilization period, each subject served as his own control, observing a high carb, medium carb and low carb diet for four weeks each. All the diets were of equal calories, intended to maintain the stable weight, so the only difference was the composition of the diets. All subjects did all diets in random order.

What they found was that there was, indeed, evidence that carbohydrate restriction worked better than other strategies. The known response of our body to reduced calories is to reduce metabolic rate. This response occurred in all the volunteers, on all the diets, but it was blunted in the low carb group. Instead of decreasing resting energy expenditure by 205 cals/day (as the high carb/low fat group did), the low carb group decreased only by only 138. Total energy expenditure (which includes activity and energy spent digesting food) was decreased by 423 cals/day in the high carb group vs. 97 cals per day in the low carb group. That's a pretty significant difference. If this finding could be reproduced in a larger study sample, the significance for dieting would be enormous. Who wouldn't rather eat the 236 calorie difference in efficiency between the two diets?

If the low carbohydrate approach has a metabolic advantage, what would be the internal mechanism? The most often proposed mechanism, from Atkins in 1971 to the present, is the concept of turning on "ketosis." This often misunderstood term refers to a state of measurable use of stored fat for fuel in the body. It is often confused, by laypersons and doctors alike with "ketoacidosis" which is a dangerous state encountered by some type 1 diabetics with dangerously low insulin levels. Ketosis, on the other hand, refers simply to the presence of "ketones" in the body at a high enough level that they can be measured in the blood or urine.

We naturally produce some ketones at all times, especially while we sleep, but at a very low level in most people. Getting a large amount of ketones in the blood happens in one of two ways: fasting, or severe carbohydrate restriction. Fasting, of course, is simply the act of severely restricting fat and protein along with the carbs, so the distinction is not terribly important. Without carbohydrate, we break down fat to ketones and other smaller molecules to supply energy to the body, with the brain first on the list. If your insulin system is still active, your body has no problem with the switch of fuels. Why low carbohydrate advocates believe that ketosis is necessary for "true" weight loss is probably because ketones come from fat breakdown, so it's considered evidence that stored fat is being burned, rather than fat that's been eaten, or mobilized from the liver or other tissues. This is probably not true and also neglects the fact that lipids, in the form of triglycerides and free fatty acids, are circulating through the body all day long. The measured ketones while dieting could easily be from your last meal. Fatty chains of shorter lengths float through the fluid of all of our cells, right next to the mitochondria, converting to ketone body intermediates when being used as fuel in alternation with glucose. There is no real need to "unlock" the particular fat molecules that reside in adipose tissue. Our cells do not seem to particularly care whether the energy production comes from fat or sugar, but seem to prefer both to protein.

The main selling point of the Atkins diet and to a lesser extent "paleo" and other low carb diets, is that you can still eat plenty of protein and fat and maintain ketosis. This allows one to avoid hunger, by "eating as much as you want," while still losing weight. While this is in some sense true, "as much as you want" when you can't include any carbohydrate is invariably many fewer calories than one would typically eat. Since carbohydrates make up 50-55% of daily calories, critics point out that avoiding half of what we normally eat is bound to make anyone lose weight. You simply can't find enough protein and fat to make up the difference. Most flavors of beef jerky are too high in carbohydrates to fit the Atkins recommendations.

At least as far back as 1976, researchers have been looking at the relative advantage of diets which promote ketosis. This was before the "obesity crisis" was conceptualized and before any noticeable shifts in macronutrients had occurred in the food supply. In the Journal of Clinical Investigation, Yang and Van Itallie subjected six “grossly obese male subjects” to three diets, each lasting ten days. The diets were: complete starvation (just non-caloric fluids), 800 calorie ketogenic diet and an 800 calorie mixed diet. These diets were given to each volunteer alternating with more relaxed periods of 1200 calorie diets:

Ketogenic diet: 25% protein, 70% fat and 5% carbohydrate

Mixed diet: 25% protein, 30% fat and 45% carbohydrate.

Fasting: 0% protein, 0% fat and 0% carbohydrate

1200 cal diet: 17% protein, 30% fat and 53% carbohydrate

(considered "balanced")

They alternated these diets in the subjects, using the 1200 calorie diets as a sort of wash-out process between the ten-day study periods. The question they were trying to answer was: does diet composition make a difference in weight loss? They were also curious to study what exactly was lost: fat, lean tissue or water. Each subject lived in the hospital for 50 days, alternating the diets while getting weighed daily, and allowing all of his urine and feces to be collected for analysis.

The researchers estimated calories burned in activity by having the subjects keep logs of all of their activities and by measuring the caloric burn by indirect calorimetry. This involves breathing into a tube which analyzes how much oxygen you are consuming in different situations. If you’re sitting still, you burn a certain amount of oxygen and this can be measured as differences in the air you inhale versus the air you exhale. If you’re running on a treadmill, naturally, you use up more oxygen than when sitting still and that is reflected in the air collected in the tube. This translates pretty well to how much energy your body is using during the different activities. The researchers recorded how many hours each volunteer spent in the different activities to estimate how many calories each were burning.

Today, if you wanted to look at body composition, you’d use a dexa scanner (the same machine we use for bone density scans). Dexa is quick, easy, and very accurate for distinguishing lean mass from fat mass. In the seventies, they did some mathematical gymnastics involving nitrogen that I won’t describe here, mostly because I don’t understand it at all. In short, they used the nitrogen balance to estimate whether muscle mass, protein balance or fat balance was changing in these subjects who lost weight. What did they find?

The starvation periods produced the most weight loss, followed by the 800 calorie ketogenic diet and then, the 800 calorie balanced diet. The subjects lost, on average, 750 grams (1.7 pounds) per day while fasting, 466 grams (1 pound) per day on the ketogenic diet and 277 grams (0.6 pounds) on the balanced, or mixed, diet as they call it.

What does this mean? Of course, fasting causes the most weight loss and it’s an excellent method for slimming down, but of limited utility in the long run. Between the other two diets, low-carb vs. balanced, does the low-carb diet really produce almost double the weight loss? 0.6 vs. 1 pound per day? Actually, no. What this study showed, very clearly by 1976 scientific standards, is that low-carb diets are, in the short term at least, dehydrating.

When they measured what was lost on the 800 calorie diets, they found that both the low-carb ketogenic and the balanced diet, produced the same amount of fat loss, same amount of muscle loss, but very different amounts of water loss. The balanced diet caused an average of 102 grams (0.2 pounds) of water loss while the ketogenic diet caused 284 grams (0.6 pounds) of water loss, daily. Incidentally, fasting was equal, percent-wise, to the ketogenic diet with regard to being dehydrating.

One conclusion we might draw from this is that a mixed, or balanced, diet that reduces calories will cause a reliable, slow weight loss and you can count on doubling that by doing the same calories without any carbohydrates. The doubling will come entirely from water loss, rather than actual fat cells giving up their contents. This study shows that low-carb works as well as another diet and gives encouraging results on the scale (which may be important for patient adherence). But the study does, perhaps suggest an explanation for how reversible our quick low carb weight loss can be: If half the weight we lose in the beginning is actually just water, we are always just a couple meals away from putting five pounds back on. The carbs, salt and the liquids that we use to wash down a restaurant meal will make us feel as if one night, or a weekend, of indulgence has reversed all of our gains, because water fluctuates so dramatically. I believe that a lot of the enthusiasm that low carb diets provoke and the following frustration they cause, is in fact due to these water shifts, which exaggerate our observations in both directions, at least in the initial phase of low-carb dieting.

The first longer term, randomized controlled trial of the specific low carbohydrate approach advocated by Atkins was published in the New England Journal in 2003. One of the authors, James O. Hill, had given a talk that same year in Washington DC that I'd attended. In response to the question of what were "three take-away points to remember for obesity treatment," Dr. Hill spontaneously responded that he could only think of two: portion control and pedometers. I thought that was a great answer (from his perspective) and I think it qualifies him as an unbiased examiner of the low carbohydrate hypothesis. In the study, the researchers compared weight loss and cardiac risk factors in a group of 63 participants at 3, 6 and 12 months, with half of the volunteers following the Atkins low carb/high protein/high fat approach and the others following a traditional low fat recommendation. What they found was that the weight loss was indeed greater for the low carb group for the first six months (7 kg vs. 3.2kg), but the difference disappeared at the one year mark. With regard to cardiac risk, the low carbohydrate diet was superior to low fat. This perhaps suggests the obvious: Atkins is better, but harder to maintain than more "reasonable" diet solutions.

In a 2007 American Journal of Clinical Nutrition comprehensive review of low carbohydrate mechanisms, Eric Westman (who is frequently quoted by Dr. Atkins in his books) and colleagues collected results from randomized controlled diet studies comparing low carbohydrate to usual weight loss recommendations. Their tabulated results of six well performed, decently large, studies show a consistent advantage of low carb over low fat diets: 9.3 kg (20.5 pounds) vs. 4.5 kg (9.9 pounds) over periods ranging 3 months to one year. These studies were long enough and used modern methods to show that the difference was not due to temporary water losses. However, within individual studies, some of the differences between the weight loss outcomes were insignificant, so that those studies, taken alone, would not support the argument that low carbohydrate diets are superior. The authors show that cardiac risk factors were either unchanged (cholesterol) or improved (triglycerides) using the low carbohydrate methods. The authors suggest, in a more scientifically rational and reserved tone than Atkins used, that there is no reason to fear low carb methods and a there is good reason to use it as the first line of defense for obesity and diabetes. It can be safely said that this group contains low carbohydrate advocates (Volek and Phinney wrote the 2010 update of the Atkins diet revolution book), but they advocate it from a more scientifically sound platform.

Notice that we keep stumbling across the finding (from 1976 to the present) that low carb diets produce about twice as much weight loss as low fat diets. The vast majority of studies looking at this question have found either that, or that there was no difference between diets. I do not believe I have ever read a study that shows low fat to be superior to low carb. The science supporting the low carb hypothesis and the proposed solution has good internal consistency: Eating carbohydrate does raise blood sugar more than eating protein or fat. It does raise insulin more than the other macronutrients (protein raises insulin about 1/2 as much, fat almost negligibly). Insulin does increase storage of energy and turn off fat breakdown. Insulin, when taken as a medicine, almost invariably causes weight gain. Furthermore, eating fewer carbohydrates does lower blood sugar and insulin. Low carb dieting is arguably more effective for weight loss. Given all this, we must ask, why do so many very good scientists reject the high carbohydrate hypothesis of obesity causation?

The low carb hypothesis feels like a coherent theory of fat cell energy regulation and it may be the simplest explanation we can use to understand why we get fat. However, it only remains coherent through a fair amount of simplification of the regulatory pathways. Nothing said about the actions of insulin is inaccurate in the high carb thinking, but the focus on insulin alone may be misguided. In addition, Insulin has a variety of actions in our body, not necessarily related to weight gain. A baseline level of insulin is secreted into the blood by the beta cells of the pancreas at all times. When insulin is low, as during our overnight fast, the liver maintains our blood sugar level through a process called "gluconeogenesis." When we eat, the pancreas responds by releasing more insulin over the course of the following two hours. Higher insulin turns off gluconeogenesis in the liver. It also manages the incoming sugar energy from the meal by opening more receptors on muscle, fat and organ cell membranes, enabling an influx of energy into cells, so that they can do work. This again, is not a bad thing, but a good thing. We, of course, would like our cells to be able to repair themselves, produce enzymes, copy DNA, fight infection, move our bodies, think big thoughts, whatever it is they are meant to do. Insulin's positive action, of helping energy get delivered, is not the problem.

The problem (according to the carbohydrate hypothesis) is that this higher level of insulin inhibits lipolysis (fat break down) and increases lipogenesis (fat creation). This is not an accidental side effect of the hormone level rising abnormally high, but part of its every day role as a regulator: While sugar is available for cells to do work, there is no need to create energy from stored fat, so the hormone which responds to sugar simultaneously acts also to stop fat breakdown. This works out very nicely. These same pathways manage energy in lean individuals as well. But the fact that one of insulin's role in the body is to stop lipolysis and simultaneously encourage lipogenesis makes it easy to see why some would consider lowering insulin levels to be effective for weight loss. We literally couldn't store fat without it.

There are a host of problems with this thinking, the most important of which is to realize that insulin does not act alone. Right next to the cells that produce and secrete insulin in the endocrine part of the pancreas, are cells that secrete its antidote: glucagon. Built into the system is a countermeasure that keeps insulin from performing its actions in an out of control manner. Glucagon's role is to figuratively follow insulin around and reverse each of its actions so that they are controlled in degree and duration. Think of insulin as a parent in a child's room putting all the toys away and glucagon as the toddler following her around, pulling things off the shelf almost as fast as they get stored. Additionally, Insulin itself has an indirect and delayed mechanism for ensuring it doesn't run amok. After a meal, insulin is one of the key appetite suppressing hormones in the brain. This ensures that the brain will receive a strong "stop eating" signal that is proportional to percentage of glucose in the meal. By this negative feedback loop, insulin itself decreases future insulin secretion, through inhibiting feeding. In addition, the baseline insulin that is secreted all day long is proportional to our body size, so insulin can be considered a regulator of our long term weight by inhibiting appetite generally to counteract our growth. The quickest criticism of the low carb diet philosophy is to say, "Why would you want to lower one of strongest satiety signals in the body?"

Showing that insulin is the proximate necessary hormone enabling fat storage is not the same as showing that it causes fat storage. The focus on insulin's action as the key step in weight gain ignores that there are a vast host of signals regulating hunger, digestion and energy usage: Ghrelin tells the brain that the stomach is empty; insulin doesn't act on it. CCK and PYY are secreted by the small intestine. They act to slow stomach emptying and tell the brain that nutrient levels are rising. Insulin doesn't affect them. Leptin and adiponectin are secreted by fat cells to give feedback on whether we are growing heavier over time. Insulin doesn't change what they do. Cortisol from the adrenal glands promotes a stress response that causes many people to eat more. It does this without asking insulin's permission. Thyroid hormone turns up the metabolic action of almost all of our cells and fluctuations in its level can cause dramatic weight loss or weight gain....again without any input from insulin. None of these hormones are related to the carbohydrate level in the diet, either. They are simply acting outside of the focus of the carbohydrate hypothesis.

The apparent disagreement between those who point out insulin's key role in fat storage and those who believe it's more complicated than that is not a disagreement about scientific facts. The two camps are really talking about different things. The low carb advocates have homed in on the major intracellular steps of regulation, while the critics are more interested in appetite control and whole body energy status. In simple terms the debate is frequently framed: "Is a calorie a calorie?" But really no debate is possible when one group is looking at cellular signaling in the liver and the other is looking at hunger regulation in the brain. Some bridging of the two areas of interest is needed to get a complete view the obesity problem. From this standpoint, I think it's more appropriate to consider insulin necessary, but not sufficient, to cause obesity. It can also be said that glucose is necessary, but not sufficient and dietary fat is necessary, but not sufficient. All three must be present. But for insulin to do its job of promoting fat storage, the appetite must allow the excess energy to enter in the first place. We are still at a loss to explain (using low carb thinking) why our intake has increased and why many individuals feel very unsatisfied on a low carbohydrate diet.

The carbohydrate hypothesis has the biochemistry nailed down. I don't believe there is much debate on that. It is in proposing dietary solutions to alter the biochemistry that low carb diet advocates run afoul of the scientists holding a more traditional view. Acknowledging that glucose is the primary stimulator of insulin does not mean that we have to eliminate, or even drastically reduce, carbs in the diet. By all measures, the increase in carbohydrate, which is thought to have caused the increase in obesity rates, is a subtle change that has crept into our diet at a very slow rate. We've increased carbohydrates perhaps 3-5%, or about 50 grams per day, gradually, over four decades. Why would we need to all but eliminate a nutrient that accounts for nearly half of our energy requirement?

By focussing too narrowly on just part of the picture, the carbohydrate hypothesis fails to account for all of the other pathways that affect our weight, most importantly, neglecting to account for appetite mechanisms that act to balance out unbalanced diet approaches. This leads to frustration from the individual following the low carb diet who states, "Sure it works, but I'm starving!" In my experience, patients almost universally consider low carb living a temporary diet to achieve quick weight loss rather than a sustainable way of eating to maintain health. I believe that the discussion of the counter-measures above helps to explain why. While it may be scientifically valid to propose that we reduce carbs to reduce insulin to reduce fat stores...Immediately, the counter-regulatory measures, working on the digestion and appetite centers, will induce us, through hunger (and specific cravings) to rebalance our feeding until our weight is restored.

The arguments above don't disprove the carbohydrate hypothesis, they merely cast doubt on the completeness of the explanation, particularly the proposed solution. Gary Taubes wrote a second book on the carbohydrate hypothesis titled simply "Why We Get Fat." This was a pared-down version of the larger thesis of Good Calories, Bad Calories, intended to be a more readable version, for a broader audience. However, the question posed in the title is not answered in the book. The carbohydrate explanation of obesity, regardless of level of detail, is an explanation of "how" we become obese, not "why." It explains how the processes that control energy work on a fundamental level, but do not account for the reason that the processes have gone awry, aside from proposing that carbohydrates act as an unbalancing influence.

Contrary to what Dr. Atkins claimed about his "vast majority" of clients, most people feel terribly hungry and dissatisfied without simple sugars and complex carbohydrates. We don't crave these foods because we are stupid, or weak willed. The food companies haven't been making them because they have evil intentions. We started milling grain 4000 years ago and our weight only began to rise 40 years ago. Carbohydrates are a staple of the human diet because we operate quite well on them. We don't need to eliminate them; we need to balance them with our other nutrients. To continue our current obesity discussion, we need to look elsewhere to uncover the reason for our increase in weight. Carbohydrates have gone up over the last forty years and supplied each of us with at least 200 calories more energy per day. The relationship between the carbs, the calories and our weight is clear. The question is not "how" we became obese, but "why?"

Comments