This marketing strategy is also common on Facebook, Twitter, and outlets like Mother Jones, where organic food, supplements, and alternatives to medicine are popular for their demographics who have money and a distrust of science.

A recent paper quantified the link between corporate media, including social media, and knowledge of COVID-19. A qualifier needs to be in place in advance. This is a survey, and if you can't trust political opinion polls as an indicator of how people will vote (you can't) or food frequency questionnaires to manufacture epidemiology links between food or chemicals and diseases (you really, really can't) then also place a giant red EXPLORATORY on this result. It is based on just under 6,000 people in one state over a year ago, when the World Health Organisation still denied COVID-19 was a pandemic because China told them it was due to American meat, and not any of the 16,000 bat virus samples in Wuhan, the world's largest coronavirus lab. And it is a convenience sample, which is just what it sounds like; unlike probability sampling, where you seek to be representative, this is just people that were easy to reach.

But the results here have an air of truthiness, and then some real truth, so let's discuss.

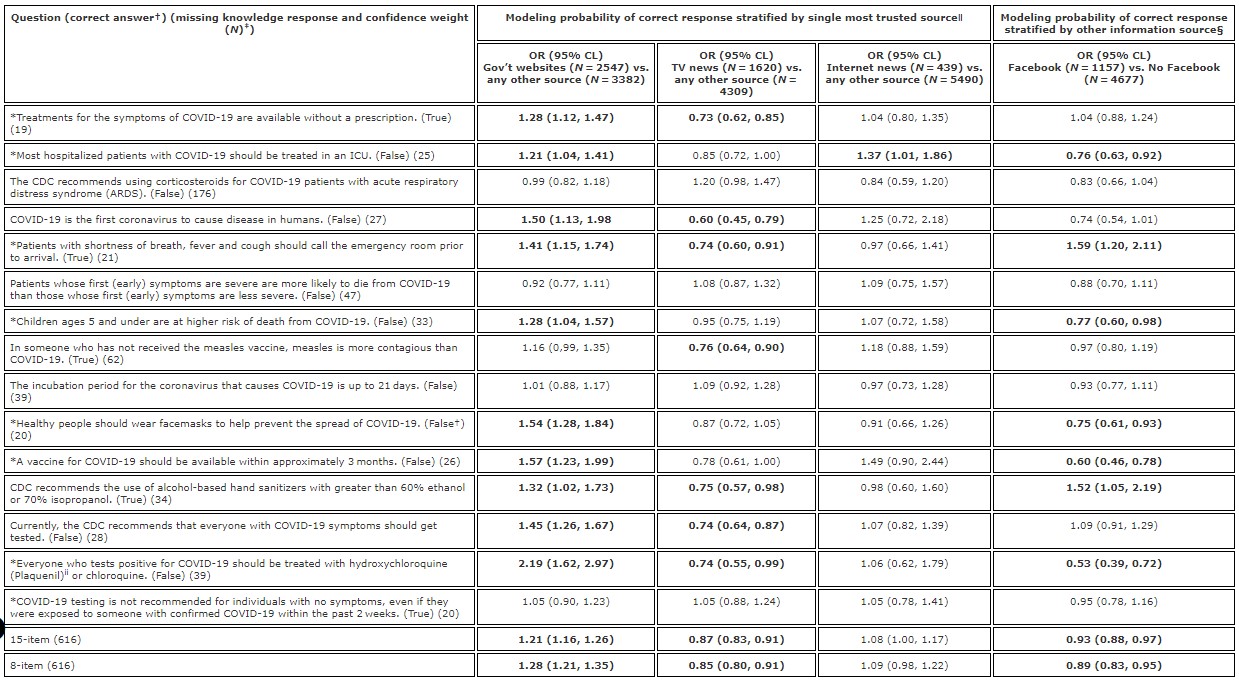

Respondents (surveys are always a confounder on anything more objective than questions such as 'do you like cilantro?') were given 15 statements about COVID-19 and asked if those were true or false.

CLICK IMAGE FOR FULL SIZE

What mitigates survey questions as a confounder in this case is that respondents were given a chance to quantify how confident they were in their response. This is an important distinction. For an analogy as to why importance matters, if I ask you if you are for or against banning guns or abortion, the response can be weighted improperly if your actual interest in the topic is negligible; for example, you are a man who does not own a gun and has never changed a vote for any politician based on what the candidate said on either issue. On food frequency questionnaires, like those monthly 'X is the new Miracle Vegetable' or 'Y chemical linked to cancer' epidemiology claims, all answers are equal, so in our analogy a man who doesn't care much about the issues cancels out, for example, a woman who feels strongly on either.

It leads to flawed data.

There is no question that nearly 70 percent of the country uses social media - and those companies pretend to be news. But social media is just aggregating things people post. If you click on a post someone made about a topic, Facebook decides you want more of it. Including if you are only reading it to ridicule it. Television is a little better. Yes, producers with no real accountability control what gets on the air, but outside politics or phoning it in by filling time with some paid influencer, they are not going to be wrong if they just parrot more trusted websites, like the CDC or Science 2.0.

Social media has no gate of any kind. And while I believe in the wisdom of crowds, that really only applies to meaningless things. If I ask a smart scientist how many jellybeans are in a jar, and then average the guesses of 100 construction workers, the latter will be more accurate almost every time.

When it comes to something important like politics, though, "Men In Black" put it best.

And politics infects almost everything.

Sure enough, people who listed a site like CDC as their most trusted source were most likely to get even difficult questions correct, while those whose most trusted source was television were far less likely to be correct.

Some of the results read worse due to framing. America has 30 percent adult science literacy, for example, and if you are a New York Times subscriber and I say it it is only 30 percent that may lead you to lament how stupid rural people and those outside the coasts are, but if I note that America actually leads the world in adult science literacy with that 30 percent you feel better about it, or you might be surprised. You might even be skeptical. Which is good, unless American literacy is the only thing you are skeptical about, and not those endorsements of acupuncture and astrology you read in the New York Times.

The authors acknowledge these limitations but given the prevalence of social media, and how anti-vaccine activists and their corporate conspiracy theorists dominated it long before 2020, it is important that we get detailed looks into the influence these companies have. I can't start a low power radio station to play music for my friends without getting government sending me warning letters and putting liens on my house but anti-science malcontents who oppose the science of food, energy, and medicine are able to pollute public trust in science unchecked.

Comments