Politics always make strange bedfellows. When George W. Bush was president, the claim of his political opposition was that Iraq was 'no harm to anyone outside its own borders' and so we should not be involved there, much less do any nation building. Yet when his political opposition gained control of the White House, the calls to do that same thing in Libya, Egypt, Syria and other places have been quite vocal. They just rationalized that they were helping an Arab Spring to flourish by removing the military power of despots.

Yet at least one political science paper disagrees. Instead, it argues that nations which go through civil war are much less likely to become democratic if the winning side gets help from enemy nations - and funding insurgency is the default response for larger countries involved in shaping geopolitics.

Receiving aid from 'the enemy' - and America is going to be considered the enemy by everyone from Nicaragua to Ethiopia if those countries watched news feeds from CNN criticizing American actions - can create mistrust among the nation's citizens and make it more difficult for the new regime to institute a democracy. Fruit of the poisoned tree, and all that. It is difficult when people are trained not to trust the west to suddenly have them regard those countries as friends.

Michael Colaresi of Michigan State University studied 136 civil wars from 1946 to 2009, 34 of which involved rivals aiding the winning side. Of those 34 countries, only one – Algeria – bucked the trend by becoming significantly more democratic over the next decade. The others either remained undemocratic or became substantially more repressive after the civil war.

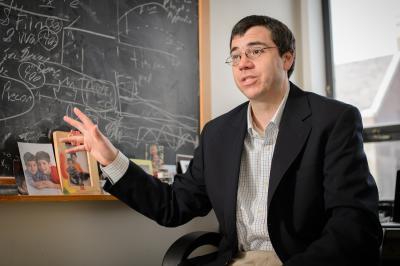

A study on modern civil wars and democracy by Michigan State University political scientist Michael Colaresi suggests countries that receive foreign aid during the war are much less likely to form democracies after. Credit: Michigan State University

The paper in the Journal of Peace Research is the first to document which events within a civil war can help to systematically forecast where post-conflict democratization is likely or unlikely to occur. Past research looked at factors such as the destructiveness of the war and whether the rebel group won, but failed to make a connection to future democracies.

Colareis says this holds even if the public was unaware of the aid during the civil war. Democracy in most cases involves greater transparency, holding elections, having a free press and an active legislature, meaning those previous unpopular ties eventually would become public – a disincentive to democratize.

In addition, anti-democratic effects of aid hold when the state providing support is itself democratic, such as the United States. "A tie to an unpopular external democracy," Colaresi said, "is still a potential electoral problem."

The findings have implications for world leaders trying to establish more democratic societies.

"If we want to build democracy and better human rights in the Middle East and other places," Colaresi said, "we have to understand why groups accept aid from rival nations and help to create incentives that drive it out or at least counterincentives to build new governance."

Comments