It has worked. When people picture a hard science like physics, they picture a university-based lab. In reality, physicists often leave academia for jobs in the private sector, pursuing careers that are traditionally not tracked in workforce surveys of the physics field. Investment banking loves people who can create models that may translate to the real world, for example.

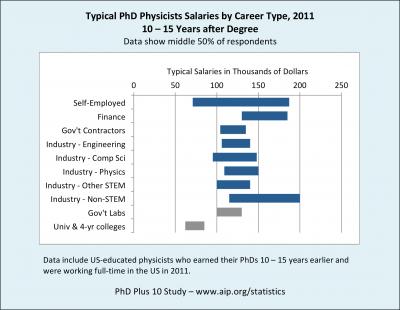

A new report is the first to systematically track PhD physicists who pursue non-academic careers and suggests that those entering the private sector around the turn of the millennium were doing quite well a decade later, even better than if they got a tenure job in academia, which has a six-figure income. According to the report, in 2011 more than three quarters of physicists working in the private sector earned in excess of $100,000 a decade after receiving their doctorates.

Credit-Statistical Research Center(SRC)/AIP

Private sector physicists also identified their jobs as intellectually stimulating, challenging and rewarding because they regularly worked with smart and interesting people from a wider range of backgrounds than they would have gotten in the less diverse halls of academia, where political and cultural beliefs will often prevent advancement regardless of ability.

The scholars tracked down 503 physicists working in the U.S. private sector 10 to 15 years after they received their doctoral degrees and asked them about the skills they used in their current jobs.

The world beyond academia presents students with a dizzying array of options, many with a less clear-cut path to success than a tenure-track professorship, so it is likely for people who like having a less planned roadmap for their career rather than someone who needs the comfort of predictability. In the survey, the mid-career physicists who responded are divided into eight broad career types, based on their primary area of work, such as self-employment, finance, and various branches of industry. Each type of career is discussed in a separate chapter that highlights the skills and intellectual and interpersonal knowledge that physicists working in that discipline tend to use the most. Two companion reports list verbatim what physicists in each field reported as the most rewarding aspects of their jobs, as well as their duties and responsibilities.

85 percent of private sector physics PhDs were still working in STEM fields, 71 percent of respondents described their jobs as intellectually challenging, and 61 percent felt that their work was appropriate for someone with their degree. Likewise, a majority of private-sector physicists who pursued post-doctoral positions after earning their degree found those additional research opportunities worthwhile.

Across the survey's eight career categories, though, some differences emerged. Unsurprisingly, physicists who pursued careers in industry -- whether in physics, engineering, or another STEM field -- reported that they frequently relied on their general scientific knowledge and their specific physics training. Those who went on to earn law or business degrees had less use for their specialized physics knowledge, but said they still relied on their science-based problem-solving abilities and math skills. Self-employed physicists particularly valued the flexibility of their jobs, as well as the opportunity to feel more in control of their own success. Government contractors appreciated the variety of projects they were able to pursue, while those in finance enjoyed high salaries.

The survey also turned up a few somewhat unexpected results. "We were surprised to find that physicists in finance often work with other physicists," said Roman Czujko, lead author of the report. In addition, nearly 80 percent of physicists working in finance felt that their job was appropriate for someone with their degree -- higher than the overall private sector average. A closer look at the data reveals that their jobs in the financial sector often involved complex mathematical modeling and simulations, using the quantitative skills that their doctoral studies had helped them develop.

In addition, physicists who were self-employed didn't fit the stereotype of a solitary worker. Rather, they often lead their own businesses, working closely with both employees and clients. The companies they founded frequently provided products or services for science and technology industries.

Comments