Marketing academics, the group who brought us the notion that hurricanes with female names are more dangerous because the patriarchy just assumes the little ladies are being hysterical and won't knock down houses, are back with the conjecture that your gambling style is genetic.

It's not as crazy as the stuff years ago that claimed liberals and conservatives were born that way, or that your grandfather's diet changed your genes enough to make you fat, but it isn't good science either. Thus, look for it on the Dr. Oz show by next week.

Investors and gamblers take note: your betting decisions and strategy are determined, in part, by your genes.

The UC Berkeley, and University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) scholars say that betting decisions in a simple competitive game are influenced by the specific variants of dopamine-regulating genes in a person's brain. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter – a chemical released by brain cells to signal other brain cells – that is commonly accepted by psychologists to be part of the brain's reward and pleasure-seeking system. Dopamine deficiency has also been implicated in Parkinson's disease, while disruption of the dopamine network has been suggested to cause numerous psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders, including schizophrenia, depression and dementia.

Dopamine is a common target for studies of social interactions but this is the first study tying these interactions to specific genes that govern dopamine functioning.

"This study shows that genes influence complex social behavior, in this case strategic behavior," said study leader Ming Hsu, an assistant professor of marketing in UC Berkeley's Haas School of Business. "We now have some clues about the neural mechanisms through which our genes affect behavior. When people talk about dopamine dysfunction, schizophrenia is one of the first diseases that come to mind.

"To the degree that we can better understand ubiquitous social interactions in strategic settings, it may help us understand how to characterize and eventually treat the social deficits that are symptoms of diseases like schizophrenia."

Like the female hurricanes paper, this was in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, lending credence to the belief that PNAS has no one at all running their editorial board.

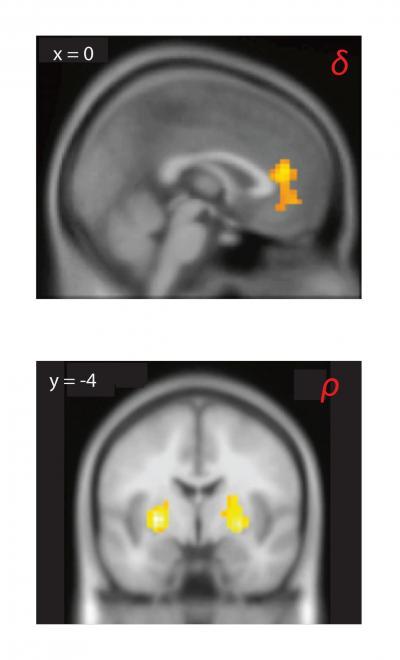

Brain scans are the most abused pretty pictures in all of science. Here they purportedly show high activity in the medial prefrontal cortex (top) and striatum (bottom) while playing a competitive game. The scholars then matchec the pretty picture to genetic variations in dopamine-regulating genes in the prefrontal cortex and striatum associated with differences in belief learning and reinforcement learning, respectively. Credit: Ming Hsu, UC Berkeley

Hsu speculated two years ago that when people engage in competitive social interactions, such as betting games, they primarily call upon two areas of the brain: the medial prefrontal cortex, which is the executive part of the brain, and the striatum, which deals with motivation and is crucial for learning to acquire rewards. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans showed that people playing these games displayed intense activity in these areas.

"If you think of the brain as a computing machine, these are areas that take inputs, crank them through an algorithm, and translate them into behavioral outputs," Hsu says. "What is really interesting about these areas is that both are innervated by neurons that use dopamine."

The authors wanted to determine which genes involved in regulating dopamine concentrations in these brain areas were associated with strategic thinking, so they enlisted as subjects a group of 217 undergraduates at the National University of Singapore, all of whom had had their genomes scanned for some 700,000 genetic variants.

The researchers focused on only 143 variants within 12 genes involved in regulating dopamine. Some of the 12 are primarily involved in regulating dopamine in the prefrontal cortex, while others primarily regulate dopamine in the striatum.

The competition was a game called patent race, commonly used by social scientists to study social interactions. It involves one person betting, via computer, with an anonymous opponent.

Trial-and-error learning vs belief learning

Using a mathematical model of brain function during competitive social interactions, Hsu and Set correlated performance in reinforcement learning and belief learning with different variants or mutations of the 12 dopamine-related genes, and discovered a distinct difference.

They found that differences in belief learning – the degree to which players were able to anticipate and respond to the actions of others, or to imagine what their competitor is thinking and respond strategically – was associated with variation in three genes which primarily affect dopamine functioning in the medial prefrontal cortex.

In contrast, differences in trial-and-error reinforcement learning – how quickly they forget past experiences and how quickly they change strategy – was associated with variation in two genes that primarily affect striatal dopamine.

Hsu said that the findings correlate well with previous brain studies showing that the prefrontal cortex is involved in belief learning, while the striatum is involved in reinforcement learning.

"We were surprised by the degree of overlap, but it hints at the power of studying the neural and genetic levels under a single mathematical framework, which is only beginning in this area," he said.

Hsu is currently collaborating with other scientists to correlate career achievements in older adults with genes and performance on competitive games, to see which brain regions and types of learning are most important for different kinds of success in life.

Comments