A report based on in vitro tests comparing the digestion of fresh human breast milk and nine different infant formulas found that free fatty acids created during the digestion of infant formula cause cellular death that may contribute to necrotizing enterocolitis, a severe intestinal condition that is often fatal and occurs most commonly in premature infants.

Premature infants fed formula are more likely to develop necrotizing enterocolitis than those fed breast milk and it is the leading cause of death from gastrointestinal diseases in premature infants, but the underlying mechanism has not been understood.

UC San Diego researchers had previously determined that the partially digested food in a mature, adult intestine is capable of killing cells, due to the presence of free fatty acids which have a "detergent" capacity that damages cell membranes. The intestines of healthy adults and older children have a mature mucosal barrier that may prevent damage due to free fatty acids. But the intestine is leakier at birth, particularly for pre-term infants, which could be why they are more susceptible to necrotizing enterocolitis.

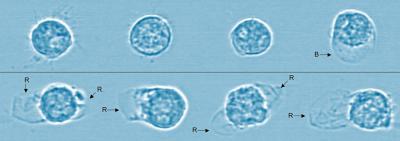

Microscopic image of cells shows the effects of breast milk versus infant formula digestion. Cells are alive and healthy after the digestion of breast milk (top row) with only one cell having any deformation. In contrast, the cells in the bottom row all ruptured after being exposed to the digestion of infant formula. Blue tint added for visual clarity. Credit: Alexander Penn, UC San Diego.

So the researchers set out to determine what happens to breast milk as compared to infant formula when they are exposed to digestive enzymes. They "digested," in vitro, infant formulas marketed for full term and pre-term infants as well as fresh human breast milk using pancreatic enzymes or fluid from an intestine. They then tested the formula and milk for levels of free fatty acids.

They also tested whether these fatty acids killed off three types of cells involved in necrotizing enterocolitis: epithelial cells that line the intestine, endothelial cells that line blood vessels, and neutrophils, a type of white blood cell that is a kind of "first responder" to inflammation caused by trauma in the body.

The digestion of formula overwhelmingly led to cellular death - cytotoxicity – in less than 5 minutes in some cases, while breast milk did not. For example, digestion of formula caused death in 47 percent to 99 percent of neutrophils while only 6 percent of them died as a result of milk digestion. Their study found that breast milk appears to have a built-in mechanism to prevent cytotoxicity. The research team believes most food, like formula, releases high levels of free fatty acids during digestion, but that breast milk is digested in a slower, more controlled, process.

Chart showing the high concentration of unbound (cytotoxic) free fatty acids (FFAs) (shown in white) created by the digestion of infant formula compared to the relatively small presence of free fatty acids formed through the digestion of breast milk. These free fatty acids are toxic to cells in vitro and may contribute to necrotizing enterocolitis, an often fatal condition that most commonly occurs in premature infants. Credit: Alexander Penn, UC San Diego.

Currently, many neonatal intensive care units are moving towards formula-free environments, but breastfeeding a premature infant can be challenging or physically impossible and supplies of donor breast milk are limited. To meet the demand if insufficient breast milk is available if the study results hold up, less cytotoxic milk replacements can be designed that pose less risk for cell damage and for necrotizing enterocolitis, the researchers concluded.

The researchers conclude that breast milk has a significant ability to reduce cytotoxicity that formula does not have. One next step is to determine whether these results are replicated in animal studies and whether intervention can prevent free fatty acids from causing intestinal damage or death from necrotizing enterocolitis.

Published in Pediatric Research.

Comments