If you are an organic food or paleo diet lover and think it means your gut microbiome resembles your ancestors in any way, you are wrong. We aren't even close to 100 years ago much less ancient times. The microbiome does not lie.

A team analyzed microbiome data from ancient human fecal samples collected from three different archaeological sites in the Americas, each dating to over 1000 years ago. They also did a new analysis of published data from two samples that reflect rare and extraordinary preservation: Otzi the Iceman and a soldier frozen for 93 years on a glacier.

"The results support the hypothesis that ancient human gut microbiomes are more similar to those of non-human primates and rural non-western communities than to those of people living a modern lifestyle in the United States," says Cecil M. Lewis Jr., professor of anthropologyat the University of Oklahoma. "From these data, the team concluded that the last 100 years has been a time of major change to the human gut microbiome in cosmopolitan areas."

The analysis demonstrated that ancient DNA can be used to understand ancient human microbiomes - meaning it will also be possible to understand recent changes to human health, such as what good bacteria might have been lost as a result of our current abundant use of antibiotics and aseptic practices.

Studying ancient microbiomes is not without problems. Assuming DNA preserves, there is also a problem with contamination and modification of ancient samples, both from the soil deposition, and from other sources, including the laboratory itself.

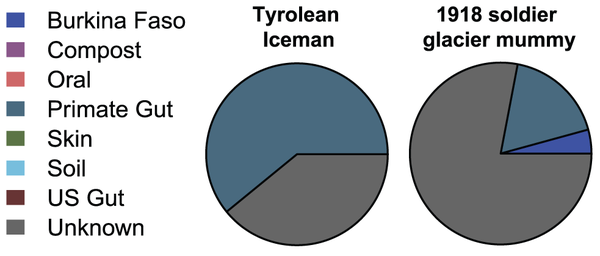

Bayesian source-tracking results for the Tyrolean Iceman and a 1918 soldier glacier mummy.

The Tyrolean Iceman sample exhibits a substantial degree of similarity to a primate gut, while the soldier mummy assigns mostly to an unknown microbial community, within minor and low-confidence proportions assigning to the primate gut and rural African child gut sources. Credit:

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051146.g004

"In addition to laboratory controls in our study, we use an exciting new quantitative approach called source tracking developed by Dan Knights from Rob Knight's Laboratory at the University of Colorado in Boulder, which can estimate how much of the ancient microbiome data is consistent with the human gut, rather than other sources, such as soil," says Lewis. "We discovered that certain samples have excellent gut microbiome signatures, opening the door for deeper analyses of the ancient human gut, including a better understanding of the ancient humans themselves, such as learning more about their disease burdens, but also learning more about what has changed in our gut today.

"Dietary changes, as well as the widespread adoption of various aseptic and antibiotic practices have largely benefited modern humans, but many studies suggest there has been a cost, such as a recent increase in autoimmune related risks and other health states," states Lewis. "We wish to reveal how this co-evolutionary relationship between humans and bacteria has changed, while providing the foundation for interventions to reconstruct what has been lost. One way to do this is to study remote communities and non-human primates. An alternative path is to look at ancient samples and see what they tell us.

"An argument can be made that remote traditional communities are not truly removed from modern human ecologies. They may receive milk or other food sources from the government, which could alter the microbial ecology of the community. Our evolutionary cousins, non-human primates are important to consider. However, the human-chimp common ancestor was over six million years ago, which is a lot of time for microbiomes to evolve distinct, human signatures."

Citation: Tito RY, Knights D, Metcalf J, Obregon-Tito AJ, Cleeland L, et al. (2012) Insights from Characterizing Extinct Human Gut Microbiomes. PLoS ONE 7(12): e51146. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051146

Comments