The need for a moral higher power may have been as necessary for adapting to a dangerous world as physical adaptations, according to a new paper.

The authors suggest that societies with less access to food and water are more likely to believe in such deities. They believe there is a strong correlation between belief in high gods who enforce a moral code and other societal characteristics. Political complexity - namely a social hierarchy beyond the local community - and the practice of animal husbandry were both strongly associated with a belief in moralizing gods, though how raising livestock factored in is a mystery, since everyone did it.

Religion has been explained as a result of either culture or environmental factors but not both. The new paper implies that complex practices and characteristics thought to be exclusive to humans arise from a medley of ecological, historical, and cultural variables.

Belief in moral, high gods may be advantageous because it fosters cooperative behavior, especially in harsh environments, according to a paper. Credit: Michael Höefner, Wikimedia Commons

"When life is tough or when it's uncertain, people believe in big gods," says Russell Gray, a professor who studies psychology and linguistics at the University of Auckland. "Prosocial behavior maybe helps people do well in harsh or unpredictable environments."

"When researchers discuss the forces that shaped human history, there is considerable disagreement as to whether our behavior is primarily determined by culture or by the environment," says first author Carlos Botero, an ecologist who studies birds at North Carolina State University. "We wanted to throw away all preconceived notions regarding these processes and look at all the potential drivers together to see how different aspects of the human experience may have contributed to the behavioral patterns we see today."

They drew their conclusions in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science by collating the beliefs of people in biology, ecology, linguistics, anthropology, and religious studies.

On a whim, Botero plotted ethnographic data of societies that believe in moralizing, high gods and found that their global distribution is quite similar to a map of cooperative breeding in birds. The parallels between the two suggested that ecological factors might play a part. They also accept anthropological claims about a connection between a belief in moralizing gods and group cooperation.

"A lot of evolutionists have been busy trying to bang religion on the head. I think the challenge is to explain it," Gray says. "Although some aspects of religion appear maladaptive, the near universal prevalence of religion suggests that there's got to be some adaptive value and by looking at how these things vary ecologically, we get some insight."

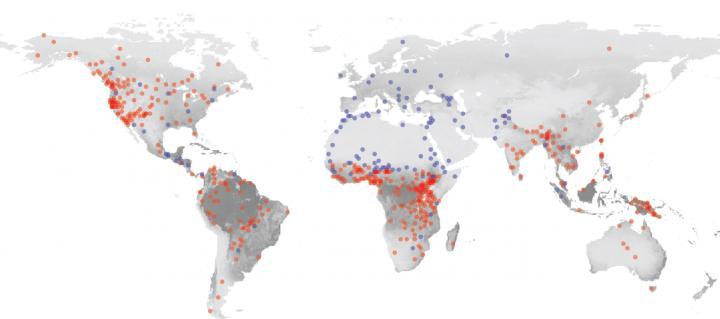

The authors examined historical, social, and ecological data for 583 societies to try and match belief in moralizing, high gods and external variables. Other anthropology claims relied on rough estimates of ecological conditions and this paper included global datasets for variables like plant growth, precipitation, and temperature. The team also mined the Ethnographic Atlas-- an electronic database of more than a thousand societies from the 20th century-- for geographic coordinates and sociological data including the presence of religious beliefs, agriculture, and animal husbandry.

This figure illustrates the distribution of societies that believe in moralizing, high gods (blue) and those that do not (red). Light gray shading indicates lower potential for plant growth with the darker areas signifying high potential. Credit: Carlos Botero

"The goal became not just to look at the ecological variables, but to look at the whole thing. Once we accounted for as many other factors as we could, we wanted to see if we could still detect an environmental effect," Botero says. "The overall picture is that these beliefs are ultimately shaped by a combination of historical, ecological, and social factors."

The team plans to further this study by exploring the processes that have influenced the evolution of other human behaviors including taboos, circumcision, and the modification of natural habitats.

"We are at an unprecedented time in history," Botero says. "Now we're able to harness both data and a combination of multidisciplinary expertise to explore these kinds of questions in an empirical way."

Comments