Everything from bisphenol A used in plastics to neonicotinoid pesticides to glyphosate weed-killers are criticized by lawyers at environmental groups despite the science consensus. How can the public know which ones really pose threats to our health and environment and which ones are just studies designed to keep poisoning lab animals until they show an effect?

Scientific research provides a likely answer, says Prof. Glen Van Der Kraak from the Department of Integrative Biology at the University of Guelph, but that research can lead to another potential problem: How to make sense of a pile of sometimes-conflicting studies on the effects of environmental chemicals?

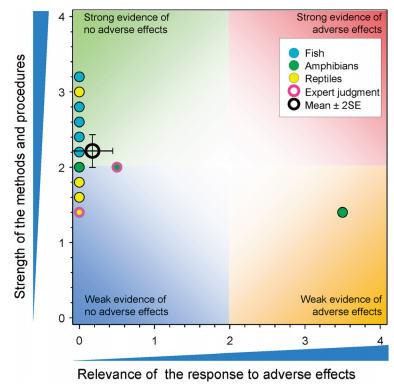

A “weight of evidence” approach offers a new way to assess research studies, including those used in coming up with environmental regulations, says Van Der Kraak. He and Prof. Emeritus Keith Solomon, School of Environmental Sciences, and colleagues co-authored a paper on the topic published recently in the journal Critical Reviews in Toxicology. The paper describes the use of their approach to look at atrazine, a common herbicide used on important food crops such as corn, sorghum and sugar cane. The herbicide has been in use since 1959 and has been re-registered numerous times by the United States EPA. EPA-approved studies found that the chemical is not harmful to fish, amphibians and reptiles (and humans cannot legitimately consume enough to get a harmful effect) but some papers have claimed otherwise. In their analyses, the EPA found that studies finding harm lacked a legitimate methodology or did not include any data but to the public, "study" and "journal" carries the weight of scientific legitimacy.

WoE analysis of the effects of atrazine on hatching in fish, amphibians, and reptiles. DOI: 10.3109/10408444.2014.967836

Because it has been studied for decades, atrazine was a good proof-of-concept to determine a weight of evidence approach for separating good studies from shoddy ones. Looking at more than 200 published papers on the topic, the researchers developed a scoring system to assess the strength and relevance of the experimental methods used by the papers’ authors. That allowed them to weigh evidence for effects of atrazine at concentrations found in the environment.

They found that the chemical can affect such things as expression of genes and proteins, hormone concentrations and biochemical processes. But those effects caused no health problems in animals, including clawed frogs studied by Solomon in South Africa.

“Some reports said there were negative effects on frog development,” says Van Der Kraak, associate dean (research) in the College of Biological Science. “Others, including our own, said there were negligible effects or only at concentrations well above what are occurring in the environment.”

He says their weight of evidence approach might help regulators in setting environmental policy.

“We all want to know the best available information is being used when making decisions, but in doing that, we need to take into account all of the available information and do it in a systematic and transparent fashion. This is one of the first instances attempting to do that.”

Regulatory agencies in Canada and the United States allow use of atrazine with warnings about limiting exposure. A few European nations have banned the chemical after environmental lobbying cited the same studies the EPA considered invalid. Referring to conflicting study results, Van Der Kraak says, “The literature is rife with controversy. People tend to select literature supporting their point of view.”

The new approach will help scientists and regulatory agencies trying to reconcile research results involving other substances, he says. “Researchers working on toxic impacts of environmental chemicals have trouble evaluating multiple studies that often give conflicting results. Our paper provides a framework that others can use or adapt.”

Solomon adds: “We think this has taken us a long way toward having a good transparent process that can be applied.”

They plan to look further at using weight of evidence for assessing some of the thousands of other human-made compounds in the environment.

Citation: Glen J. Van Der Kraak , Alan J. Hosmer , Mark L Hanson , Werner Kloas , Keith R Solomon, Effects of Atrazine in Fish, Amphibians, and Reptiles: An Analysis Based on Quantitative Weight of Evidence, Critical Reviews in Toxicology Dec 2014, Vol. 44, No. S5, Pages 1-66: 1-66. DOI: 10.3109/10408444.2014.967836. Source: University of Guelph, Andrew Vowles

Comments