Ethanol is not great. Even Al Gore had to eventually concede he had made a mistake in promoting it for almost two decades once it became common knowledge that driving food prices up for a costly, energy-negative alternative to gasoline that didn't improve the environment was a bad idea.

But what if it weren't energy negative or costly and used a lot less corn?

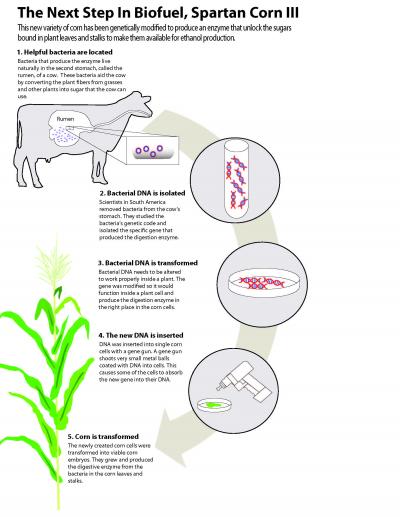

Cows, with help from bacteria, convert plant fibers, called cellulose, into energy, but this is a big, expensive step for biofuel production. In the commercial biofuel industry, only the kernels of corn plants can be used to make ethanol, but this new discovery would allow the entire corn plant to be used – so more fuel can be produced with less cost.

Cows do this with an enzyme from a microbe that lives inside a cow’s stomach that allows a cow to digest grasses and other plant fibers can be used to turn other plant fibers into simple sugars. These scientists have discovered a way to grow corn plants that already contain this enzyme. They have inserted a gene from a bacterium that lives in a cow’s stomach into a corn plant. Now, the sugars locked up in the plant’s leaves and stalk can be converted into usable sugar without expensive synthetic chemicals.

“The fact that we can take a gene that makes an enzyme in the stomach of a cow and put it into a plant cell means that we can convert what was junk before into biofuel,” said Mariam Sticklen, MSU professor of crop and soil science, at the American Chemical Society meeting in New Orleans.

Turning plant fibers into sugar requires three enzymes. The new variety of corn created for biofuel production, called Spartan Corn III, builds on Sticklen’s earlier corn versions by containing all three necessary enzymes.

The first version, released in 2007, cuts the cellulose into large pieces with an enzyme that came from a microbe that lives in hot spring water. Spartan Corn II, with a gene from a naturally occurring fungus, takes the large cellulose pieces created by the first enzyme and breaks them into sugar pairs.

Spartan Corn III, with the gene from a microbe in a cow, produces an enzyme that separates pairs of sugar molecules into simple sugars. These single sugars are readily fermentable into ethanol, meaning that when the cellulose is in simple sugars, it can be fermented to make ethanol.

“It will save money in ethanol production,” Sticklen said. “Without it they can’t convert the waste into ethanol without buying enzymes – which is expensive.”

The Spartan Corn line was created by inserting an animal stomach microbe gene into a plant cell. The DNA assembly of the animal stomach microbe required heavy modification in the lab to make it work well in the corn cells. Sticklen compared the process to adding a single Christmas tree light to a tree covered in lights.

“You have a lot of wiring, switches and even zoning,” Sticklen said. “There are a lot of changes. We have to increase production levels and even put it in the right place in the cell.”

If the cell produced the enzyme in the wrong place, then the plant cell would not be able to function, and, instead, it would digest itself. That is why Sticklen found a specific place to insert the enzyme. One of the targets for the enzyme produced in Spartan Corn III is a special part of the plant cell, called the vacuole. The vacuole is a safe place to store the enzyme until the plant is harvested. The enzyme will collect in the vacuole with other cellular waste products

Because it is only in the vacuole of the green tissues of plant cells, the enzyme is only produced in the leaves and stalks of the plant, not in the seeds, roots or the pollen. It is only active when it is being used for biofuels because of being stored in the vacuole

“Spartan Corn III is one step ahead for science, technology, and it is even a step politically,” Sticklen said. “It is one step closer to producing fuel in our own country.”

Sticklen’s research was funded by MSU and the Consortium for Plant Biotechnology Research. The work also is presented in the “Plant Genetic Engineering for Biofuel Production: Towards Affordable Cellulosic Ethanol” in the June edition of Nature Review Genetics.

Comments