Paying himself to emit greenhouse gases sounded ridiculous but a new analysis shows that buying offsets - paying a company to plant trees - can be just plain risky.

Forests absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, but if they are managed by a group that doesn't believe in logging or clearing brush. If a forest goes bust in a fire all that stored carbon goes up in smoke again.

Credit: David Meikle, The University of Utah

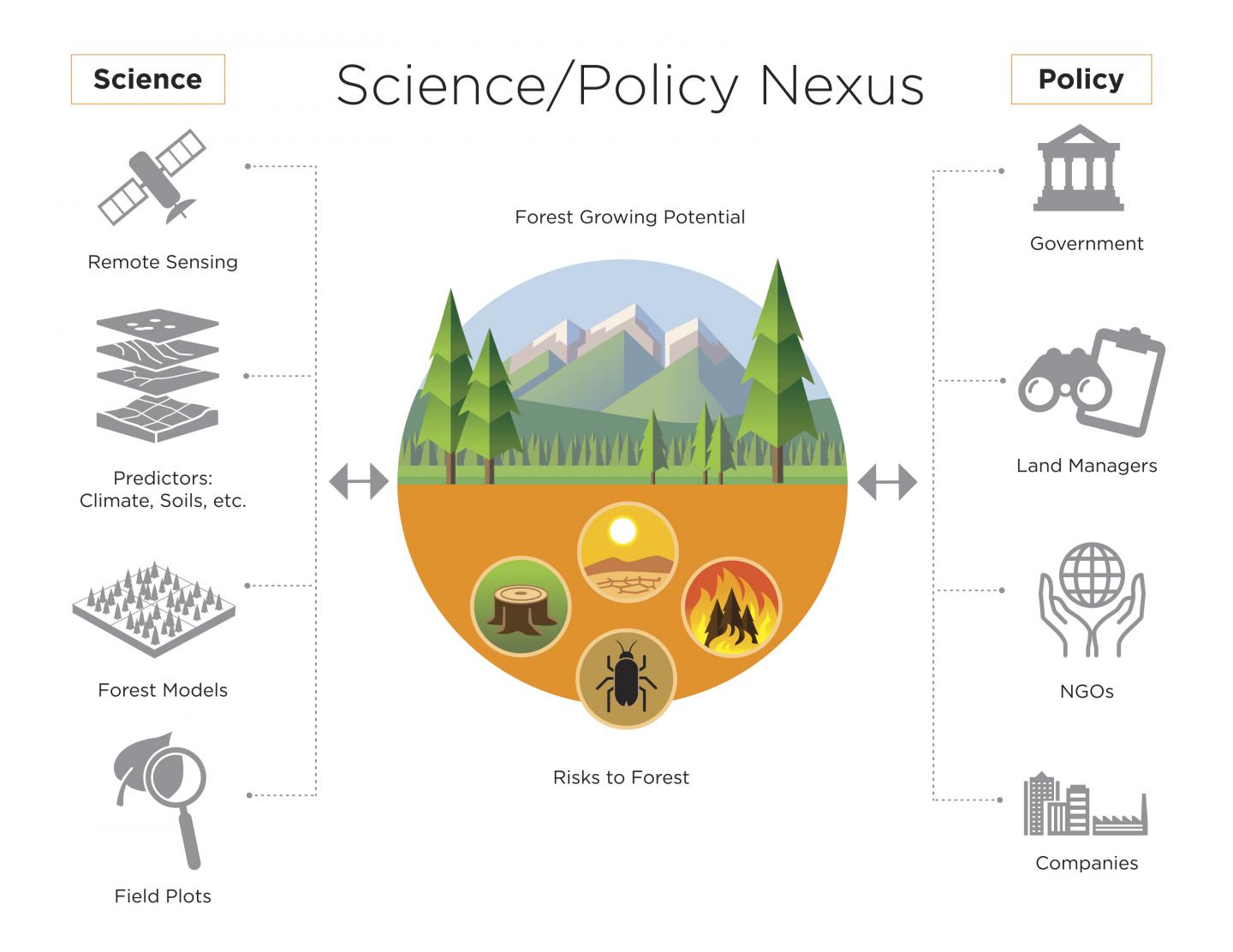

The paper calls attention to the risks forests face from myriad consequences of rising global temperatures, including fire, drought, insect damage and human disturbance - a call to action to bridge the divide between the data and models produced by scientists and the actions taken by policymakers. Since Terrestrial ecosystems absorb and store a third of the carbon emissions human activities release each year, governments in many countries are looking to "forest-based natural climate solutions" that include reforesting.

Built into that strategy is the idea that forests are able to store carbon for 50 to 100 years or more. But that is in an ideal case. Natural pests are a risk, fire is a risk, hurricanes are a risk.

Forests have always been vulnerable, and have been able to recover from them when they are episodic or come one at a time, but some climate change scenarios speculate drought and fire could increase over time. Multiple threats at once, or insufficient time for forests to recover from those threats, can kill the trees, release carbon and undermine the entire premise of forest-based natural climate solutions.

The paper's authors encourage scientists to focus increased attention on assessing forest climate risks and share the best of their data and predictive models with policymakers so that climate strategies including forests can have the best long-term impact. For example, the climate models that scientists use are detailed and cutting-edge, but aren't widely used outside the scientific community--so policymakers might be relying on science that is decades old.

Comments