A new study also shows that annual flu vaccines increasingly help protect young people during flu pandemics. Kids who receive years of season-specific flu vaccines develop antibodies that also provide broader protection against new strains, including those capable of causing pandemics.

The same ability does not exist in adults.

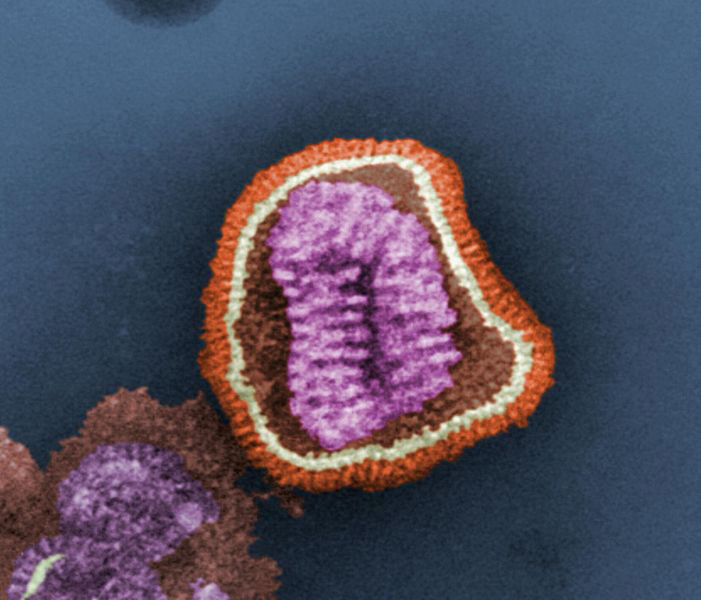

Fermiliab image shows the detailed structure of the influenza virus, taken with transmission electron micrograph (TEM).

Since children won't have been infected with and vaccinated against flu many times throughout their lives the way adults have, their immune responses are fundamentally different. The researchers spent three years studying immune responses in children between the ages of 6 months and 17 years. They found that as the children grew older, they became less capable of producing broadly protective antibodies, because of their repeated exposure to influenza, through infection or vaccination.

While COVID-19 related measures such as distancing and masking have also resulted in lower rates of influenza, like coronavirus the flu will return, and like coronavirus possibly in dangerous forms. Flu pandemics have happened 5 times in the last century. The worst,the Spanish Flu of 1918, killed at least 50 million people worldwide, which would be 200 million today. If 50 million isn't undercounted.

The research compared two forms of vaccine: the conventional flu shot and a nasal spray vaccine that works in the upper respiratory tract, where infection first takes hold. Both worked equally well at generating broadly protective antibodies, which is welcome news for parents seeking a painless alternative to needles.

“This is an important finding because it means we have flexibility in terms of the type of vaccines we can use to make a universal vaccine for children. We now know that children’s immune systems are much more flexible than adults’ when it comes to being able to teach them how to make these broadly protective responses,” says lead author and McMaster University Professor Matthew Miller.

Comments