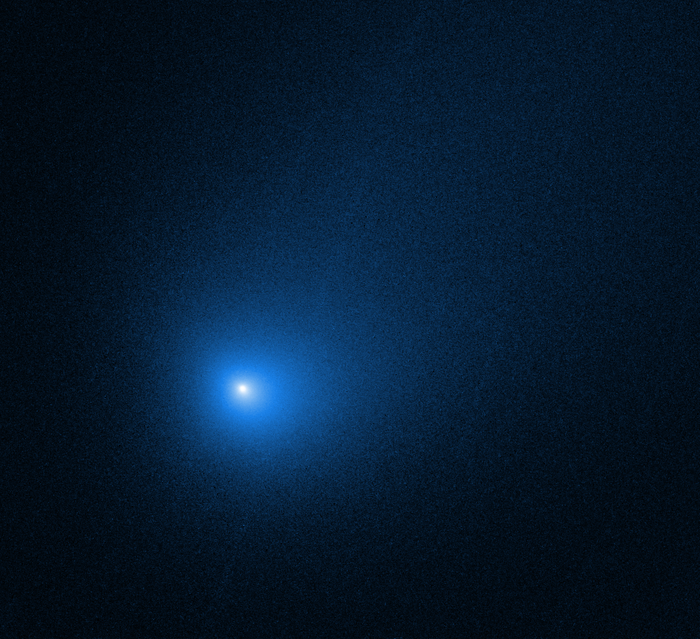

Now named Borisov, it was the first interstellar comet ever detected by humans. That doesn't make it rare.

A new computer estimate instead believes that in the Oort Cloud—a shell of debris in the farthest reaches of our solar system—interstellar objects outnumber objects belonging to our solar system.

Borisov comet. Credit: NASA, ESA and D. Jewitt (UCLA)

The calculations, made using conclusions drawn from Borisov, include significant uncertainties, but are reasonable inference.

“Let’s say I watch a mile-long stretch of railroad for a day and observe one car cross it. I can say that, on that day, the observed rate of cars crossing the section of railroad was one per day per mile,” says Amir Siraj of the Center for Astrophysics managed by Harvard&Smithsonian. “But if I have a reason to believe that the observation was not a one-off event—say, by noticing a pair of crossing gates built for cars—then I can take it a step further and begin to make statistical conclusions about the overall rate of cars crossing that stretch of railroad.”

Just because we only detected one in 2019 doesn't mean they weren't happening, it just means technology needed to catch up.

The Oort Cloud spans a region some 200 billion to 100 trillion miles away from our Sun—and unlike stars, objects in the Oort Cloud don’t produce their own light. Those two factors make debris in the outer solar system incredibly hard to see.

Comments