Is any of that real? Sure, things can be real even if they are subjective. What is certain is that once basic needs are met and the end looms a little closer, people begin to ponder the Deeper Meaning Of Life. A personal redemption narrative of 2015 could just as easily be a 1980s mid-life crisis or an existential crisis of 1915. It's a puzzle for philosophers and existentialists and phenomenologists because it has been a part of culture probably for as long as there has been culture, and it is a bedrock for all religion: When you look back on your life, how will you see yourself?

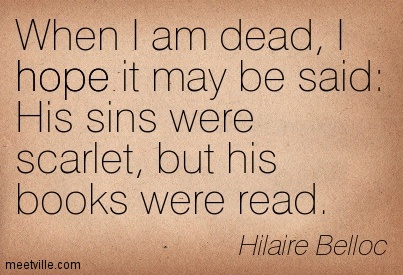

For me, this would be a pretty good way to go out:

But it wouldn't even be original, which is not exactly a great thing for a writer. Perhaps I am not at the age where I have thought it through, perhaps it is too subjective and I never will. Yet not everything about our narratives are subjective, there are common threads many of us do share. As the saying goes, no one on their death bed says they wish they had spent more time working at the office.

Some have thought it through and do try to manufacture a legacy. They want to be memorable so they create crisis after crisis in order to feel like they Live In Important Times. Doomsday prophets in one group might say Gaia is going to unleash her mighty wrath on us due to global warming or pesticides, another may believe a savior who looks a lot like them is going to return and only take the most annoying and smug among us to heaven. They truly hope it happens, so they can be right rather than help people.

They are not all that different from each other. Repent and atone is the message both groups share.

Repent and atone does not work for everyone yet it seems to work for a lot of people. Writing in Psychological Science, Dan McAdams and Jen Guo found through interviews with middle-aged people that those who thought about their lives the way we might think of a series of chapters in a book - a narrative - were more likely to engage in atoning by engaging in prosocial behavior now, even if they did not always. Like directors of films, we know if we don't get the final third right, people aren't going to think well of us. Everyone can recall happy and sad moments in their lives, high points and low points, and those can be easily cataloged, but when asked about what the next chapter should be, people in interviews were more prosocial, and the more their life matched a redemptive narrative - you had it good, you learned others had it bad, you wanted a better world, you set out to change it despite personal travails - the more likely they were to be motivated by that idea of personal redemption.

That's much different than the more common 'live fast, die young and leave a pretty corpse' thinking of the young. Middle-aged people know there aren't any pretty corpses.

Prosociality has always been a debate in religions as well, though the terms I use in this case are Catholic because it is St. Patrick's Day and no effort at forced topicality on my part can be spared. "Grace", with all of its internal undertones and subtle meanings, versus external "Good Works". A rich elite cannot show up at a soup kitchen for a photo op and donate some money and expect that will make them a better person, while someone who feels like they have grace and yet helps no one isn't really meriting a spot in the pantheon of greats either.

But some demographics seem to have a better handle on this 'generativity' - thinking about impact on future generations - than others.

“We were surprised to find that African American adults in our sample actually had higher levels of generativity and more pronounced redemptive life stories compared to the white participants,” says McAdams. “The narrative rhetoric of redemption seems to resonate deeply with especially generative African American adults, perhaps in part because of the central place of the African American church in the Black community.”

I suppose if we are going to write a book about our lives, most of us would want to come out looking like heroes, so while I am not sure what the African-American church is that he thinks the Black community attends, if you aren't sure how to start creating a redemptive narrative, they might be a good group to ask.

Citation: Dan P. McAdams, Jen Guo, 'Narrating the Generative Life', Psychological Science 0956797614568318, March 5, 2015 doi:10.1177/0956797614568318

Comments