By Barbara Sahakian, University of Cambridge and Muzaffer Kaser, University of Cambridge

Depression is a major, if not the major, cause of suicide. Every year, almost one million people die from suicide around the world. Depression is often seen as a disorder of the developed world; mental disorders – in particular depression but also disorders from alcohol misuse – have been clearly linked to suicide in high-income countries. But depression in low and middle-income countries is also a big problem and the prevalence is not dramatically different from high income countries. However, reliable data from some regions of the world – notably Africa – is not available.

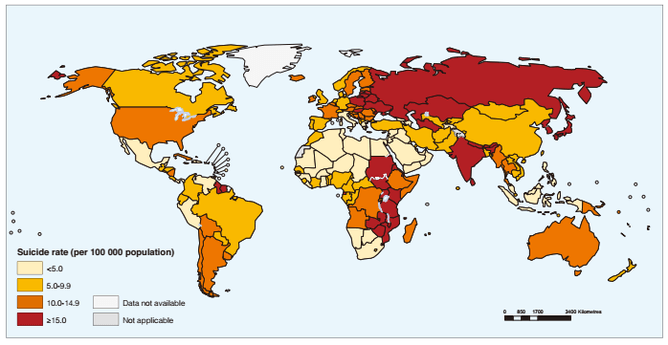

Suicide is certainly a global problem. According to a new report from the World Health Organisation – the first time it has published one – some 75% of suicides happen in low and middle-income countries. Depression is a major risk factor for suicide across the globe. While many suicides are impulsive, because of issues related to finance, illness and other pain, and particular groups who are more vulnerable, it is striking that studies have shown that depression is a significant risk factor for suicide attempts and the relationship is consistent across all countries (high or low-middle income).

Age-standardized suicide rates per 100,000 population, 2012.Source: WHO Preventing Suicide Report

And if someone suffers from multiple mental health problems such as depression, alcohol abuse and impulse control disorders, the risk is even higher. In the UK investigations suggested two thirds of people with suicidal behaviour are depressed. But depression is rarely in the headlines unless it involves a famous figure.

Although global suicide rates are highest in people older than 70, this is markedly different in particular countries where young people are more likely to take their lives. Worldwide, it is the second biggest cause of death in 15 to 29-year-olds, and in the UK, it’s the most common cause of death in men aged between 20 and 49.

Then there are the attempts, which are estimated to be 20 times more frequent than those that are completed.

National strategies

The WHO identifies only 28 countries with national strategies for preventing suicide. While reports indicate similar rates of depression in low to middle-income countries, there are regions where reliable epidemiological data is lacking. Mental health services in these countries can also be very limited.

But having a strategy isn’t necessarily the same as having one that works. Shockingly, as revealed in one report, the majority of people who killed themselves in the UK were not in contact with health services close to the time of the suicide.

Long-term studies document that in patients who receive proper treatment for depression, suicide risk is dramatically reduced. Depression isn’t just triggered by low points in life, there are biological triggers too.And in addition to mental health services, biomarkers for suicide are urgently needed to determine those with depression who are at the greatest risk.

Introducing effective interventions and policies, and reducing stigma could have a major effect on the global burden of depression.

Depression, if detected early enough, can be treated. Despite this, depression still goes largely under-recognised and under-treated. Stigma is a major problem and it doesn’t just come from those outside. Patients themselves also suffer from self-stigma, which leads to further withdrawal.

There are many different obstacles to effective treatment for depression. Cultural, work employment, psychological and cognitive factors, as well as the capacity for mental health services to provide early treatment, all play a role. The deleterious effects of depression are not confined to the patients, affecting carers, colleagues, and the society as a whole.

The burden of depression is not only great for the individuals and their families, but also for society. According to the WHO, depression is projected by 2020 to be the second leading cause of global burden of disease. In the UK alone the bill for mood disorders is around £16.1 billion. Mental health disorders, particularly depression, are the most common cause for absenteeism from work. In addition, when people are depressed at work, they may under-perform, conversely called presenteeism.

Despite this heavy burden on society, the funding for mental health research is below that of other areas of medical research. Mental health should be considered as important as physical health.

Later detection, poorer response

Early detection and treatment of depression is vital. Longer duration of untreated illness is related to poorer response to treatment. People who remain untreated are also more likely to relapse and suffer from a more chronic course. Depression affects neurochemicals in the brain, as well as the structure and function of brain systems. If depression becomes chronic and relapsing, further brain changes occur. For example, repeated episodes of depression are associated with shrinkage of the hippocampus, a brain structure which has a role in episodic memory. Timely and effective treatment of depression is key to preserving well-being, cognition and functionality at school, work and home.

Depression is a serious mental health problem with many consequences, including suicide. Effective treatment of depression could save lives. Depression is known to have both genetic and environmental influences and requires increased awareness by government, business and society. Action is needed now to determine how we can ensure that individuals with depression receive the early and effective treatment that they urgently need.

Barbara Sahakian, Professor of Clinical Neuropsychology at University of Cambridge, consults for Cambridge Cognition, Servier and Lundbeck. She holds a grant from Janssen/J&J. She holds shares in CeNeS and share options in Cambridge Cognition. She is also associated with the Human Brain Project.

Muzaffer Kaser, Psychiatrist, PhD candidate at University of Cambridge, is funded by IDB-Cambridge International Scholarhip and receives support from his affiliated institution, Bahcesehir University, Istanbul, Turkey.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Comments