Researchers have discovered the genetic machinery that turns the common gut bacterium Bacteroides ovatus

into the Swiss Army knife of the digestive tract, helping us metabolize a main component of dietary fiber from the cell walls of fruits and vegetables.

The findings illuminate the specialized roles played by key members of the vast microbial community living in the human gut, and could inform the development of tailored microbiota transplants to improve intestinal health after antibiotic use or illness.

About 92 percent of the population harbors bacteria with a variant of the gene sequence, according to the researchers' survey of public genome data from 250 adult humans.

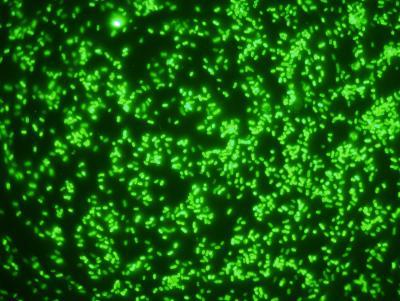

Bacteroides ovatus, wild strain. Credit: Harry Brumer, UBC

"While they are vital to our diet, the long chains of natural polymeric carbohydrates that make up dietary fiber are impossible for humans to digest without the aid of our resident bacteria," says University of British Columbia

chemistry professor Harry Brumer, senior author of the study. "This newly discovered sequence of genes enables Bacteroides ovatus to chop up xyloglucan, a major type of dietary fiber found in many vegetables – from lettuce leaves to tomato fruits. B. ovatus and its complex system of enzymes provide a crucial part of our digestive toolkit."

"The next question is whether other groups in the consortium of gut bacteria work in concert with, or in competition with, Bacteroides ovatus to target these, and other, complex carbohydrates," says Brumer.

Source: University of British Columbia

Comments