However, there is a rather blaring difficulty with this view, and it is encapsulated in the following question: If our brains are computers, why doesn’t size matter? In the real world of computers, bigger tends to mean smarter. But this is not the case for animals: bigger brains are not generally smarter. Most of the brain size differences across mammals seem to make no behavioral difference at all to the animal.

Instead, the greatest driver of brain size is not how smart the animal is, but how big the animal is. Brain size doesn’t much matter – instead, it is body size that matters. That is not what one would expect of a computer in the head. Brain scientists have long known this. For example, take a look at the plot below showing how brain mass varies with body mass. You can see how tightly correlated they are. If one didn’t know that the brain was the thinking organ and consequently lobbed it into the same pile as the liver, heart and spleen (FYI, I keep my pile of organs in the crawl space), then one would not find it unusual that it increases so much with body size. Organs do that.

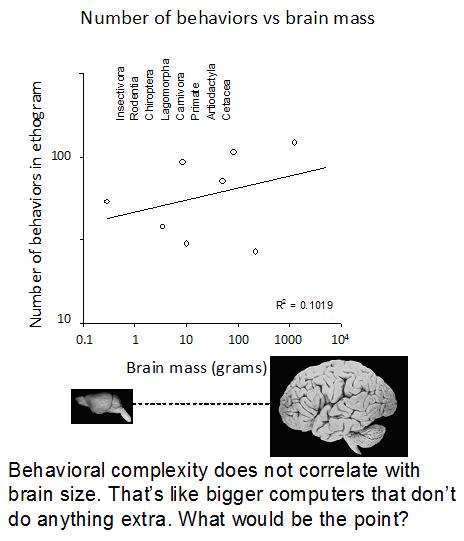

But the brain is supposed to be a computer of some strange kind. And yet it is acting just like a lowly organ. It gets bigger merely because the animal’s body is bigger, even though the animal may be no smarter. The plot below, from a 2007 article of mine (in Kaas JH (ed.) Evolution of Nervous Systems. Oxford, Elsevier) shows how behavioral complexity varies with brain mass. There is no correlation. Bigger and bigger brains, and seemingly doing nothing for the animal!

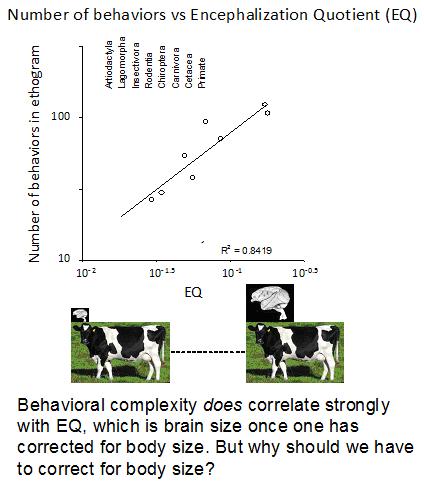

It has long been clear to neuroscientists that what does correlate nicely with animal intellgence is how high above the best-fit line a point is in the brain-versus-body plot we saw earlier. This is called the encephalization quotient, or EQ. It is simply a measure of how big the brain is once one has controlled for body size. EQ matches our intuitive ranking of mammalian intelligence, and in a 2003 paper (in the Journal of Theoretical Biology) I showed that it also matches quantitative measures of their intelligence (namely, the number of items in ethograms as measured by ethologists). The plot is shown below, where you can see that the number of behaviors in each of the mammalian orders rises strongly with EQ.

But although this is well known by neurobiologists, there is still no accepted answer to why brains get bigger with body size. Why should a cow have a brain 200 times larger than a roughly equally smart rat, or 10 times larger than a clearly-smarter house cat? One of my older research areas, in fact, aimed to explain why brains change in the ways they do as they grow in size from mouse to whale (http://www.changizi.com/changizi_lab.html#neocortex), and yet, embarrassingly, I have no idea why these brains are increasing with body size at all. If a dull-witted cow could just stick a tiny rat brain into its head and get all the behavioral complexity it needs, then brains would come in just one size, and I would have had no research to work on concerning the manner in which brains scale up in size.

So, here’s a plan. I would like to hear your hypotheses for why brains increase so quickly with body mass (namely as the 3/4 power). I will let you know if the idea is new, and I will see if I can give your idea a good thrashing. What’s at stake here is our very framework for conceptualizing what the brain is. Perhaps you can say why it is a computer, and that greater body size brings in certain subtle computational demands that explain why brain volume should increase as it does with body mass. Or, more exciting, perhaps you can propose an altogether novel framework for thinking about the brain, one that makes the enigmatic “size matters” issue totally obvious.

To the comments!...

Comments