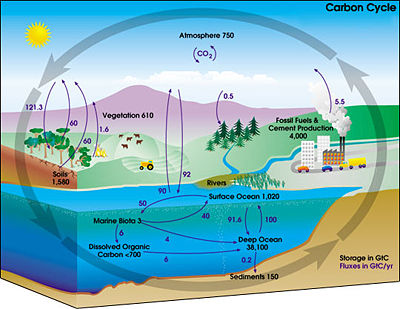

Contrary to the conclusions of dozens of other studies, a new paper appearing in Global Change Biology argues that as the climate warms and growing seasons lengthen, subalpine forests are likely to soak up less carbon dioxide. The authors, scientists at the University of Colorado, say that more of the greenhouse gas will be left to concentrate in the atmosphere as a result.

The researchers found that while smaller spring snowpack tended to advance the onset of spring and extend the growing season, it also reduced the amount of water available to forests later in the summer and fall. The water-stressed trees were then less effective in converting CO2 into biomass. Summer rains were unable to make up the difference.

When people think of the Cold War they tend to dwell on all the negatives that came with it: totalitarian governments, proxy wars, a nuclear arms race, and so on. But looking back on the period, the authors of a new paper in the journal Biological Conservation say there was an odd ecological benefit that resulted from the interruption of trade that occurred between Eastern and Western Europe during the Cold war--fewer invasive species.

"Global trade is a real concern for invasive species, and the lessons we can learn from the Cold War offer a warning flag to developing countries that are now expanding in an international economy," said co-author Susan M. Shirley.

While fossils may provide some tantalizing clues about human history, they also lack vital information needed to understand the past, such as which pieces of human DNA have been favored by evolution because they confer beneficial traits. Those genetic signs can only be revealed through studies of modern humans and other related species, and in a new Science Express paper, researchers describe a method for pinpointing these preferred regions within the human genome.

Researchers from the University of Bristol have analyzed the teeth of a 30,000-year-old child originally found in the Abrigo do Lagar Velho, Portugal in 1998. Classified as a modern human with Neanderthal ancestry, the child raises controversial questions about how extensively Neanderthals and modern human groups of African descent interbred when they came into contact in Europe

Blanket subsidies for hybrid electric vehicles won't get drivers out of their old gas guzzlers and into the new energy efficient cars, according to a new study in Energy Policy. When it comes to pumping up the appeal of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), researchers say some regions are more ripe for the cars than others, and some consumers' buttons need more pushing than others.

The study found that giving consumers who live and drive in regions where the social benefits of electric–boosted cars are strongest, and recognizing the circumstances of consumers – such as their income, life stage and family size – gives PHEVs a better shot at both sales and environmental and energy security effectiveness.

If your friends and family give you trouble for spending too much time on your cell phone, scientists at the University of South Florida may have discovered the ultimate excuse for your constant yakking. In a surprising study published today in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, researchers reported the first evidence that long-term exposure to electromagnetic waves associated with cell phone use may actually protect against, and even reverse, Alzheimer's disease. The study also challenges claims that EMF exposure causes brain cancer

Researchers at the American Museum of Natural History and the University of Cambridge have developed models they say explain how earth survived its birth. Presenting their findings at the 2010 meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Washington, D.C., the team suggests that variations in temperature can lead to regions of outward and inward migration that safely trap planets on orbits. When the protoplanetary disk begins to dissipate, planets are left behind, safe from impact with their parent star.

A new report published in the January 8 issue of Cell explains how plants, which are incredibly temperature sensitive, not only 'feel' the temperature rise, but also coordinate an appropriate response -- activating hundreds of genes and deactivating others; it turns out it's all about the way that their DNA is packaged. The findings may help to explain how plants will respond in the face of climate change and offer scientists new leads in the quest to create crop plants better able to withstand high temperature stress, the researchers say.

Reporting in the current online edition of the journal BMC Medicine, researchers from UCLA say they can predict the number of H1N1 flu infections that could occur during a commercial flight using novel mathematical modeling techniques. They found that transmission could be rather significant, particularly during long flights, if the infected individual travels in economy class. Specifically, two to five infections could occur during a five-hour flight, five to 10 during an 11-hour flight, and seven to 17 during a 17-hour flight.