At first, the influx of comments might have seemed benign enough. People commented that they were surprised she was female; some added they also thought she was attractive.

Nevertheless, Andrew felt uncomfortable with this deluge of benevolent sexism. “EVERY COMMENT is about how shocking it is that I’m a woman! Is this really 2013?” she tweeted in response.

Then the news media got involved. “I was trying to bury my head in the sand, hoping it would go away,” said Andrew.

But it didn't. Pointing out the sexism inherent in the comments made things worse. People became hostile. At one point, someone set up a Facebook page with Andrew's face photoshopped onto soft-core porn.

Andrew told her story as part of a panel with five other women who shared their experiences and insights into the persistence of gender bias in the science community April 12 at the Northeast Conference on Science and Skepticism in Manhattan.

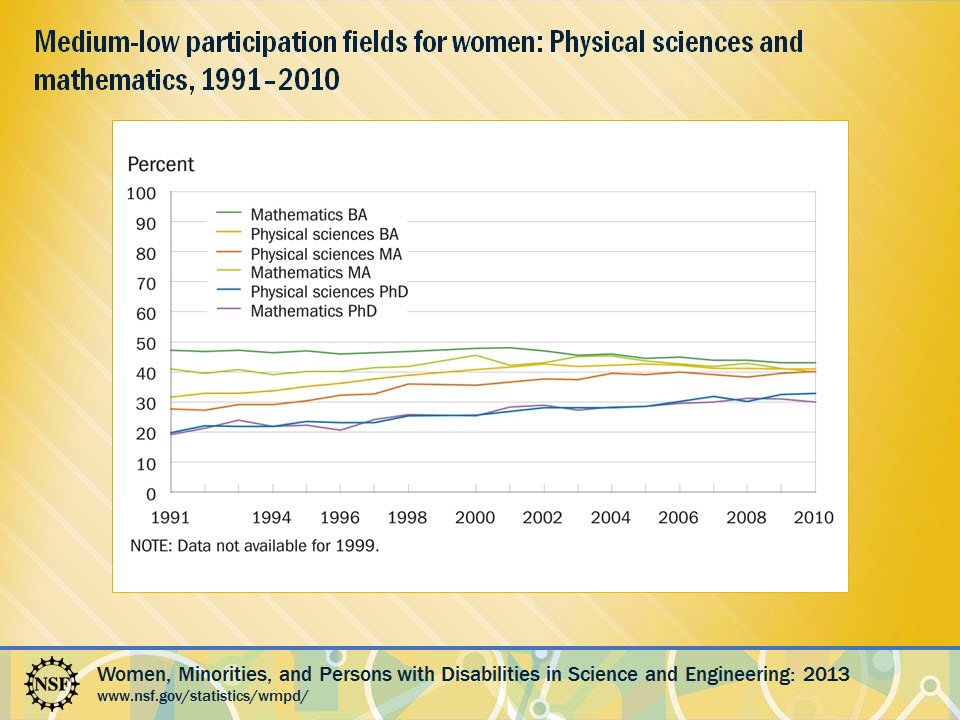

Image courtesy of the National Science Foundation.

The rest of the panel was rounded out by NASA astronaut Cady Coleman; neuroscientist Heather Berlin; Latasha Wright, Director of Development and Staff Scientist for BioBus; physicist Deborah Berebichez; and moderator Jeanne Garbarino, Director of Science Outreach at Rockefeller University.

Though Andrew hasn't ended her social media activities, she told the audience the experience has given her second thoughts about how much she puts herself in the public eye.

Coleman, for her part, said she hasn't experienced anything as extreme. “There's something about being an astronaut and going to space that makes people be nice to you,” she joked.

Nevertheless, said Coleman, she's noticed an insidious tendency for people to differentiate her from her colleagues by her gender.

She made an analogy to being a marathon runner: if you look like what people expect, they say "Go! Go!" But if you don't look like what they expect, they say, "Wow, a marathon. How is that for you?”

All the panelists acknowledged that women have more opportunities than in the past to pursue the careers and projects they want. But they also agreed that sexism in science remains entrenched in stubbornly subtle (and occasionally overt) ways.

Berebichez, for instance, had noticed that every textbook she came across was written by old, white men. The examples provided in the textbooks rarely reflected girls' experiences. So she said she put together a proposal for a book written for a girl's perspective and shopped it around. Uniformly she was told girls wouldn't buy it.

Berlin noted that there are several well-understood unconscious biases at work that continue to undermine women. One is psychological priming, exemplified by studies demonstrating that telling a group before a test that girls generally perform worse would lead to lowered scores among the females. She pointed out that numerous experiments have revealed unconscious biases against women – biases held by males and females alike.

Berlin suggested that having women in visible scientific positions could erode some of the danger of stereotypes over the long run.

However, she cautioned, it was important not to conflate the need for equality with an assumption of similarity. “It's okay to say that there are differences. There are differences between men and women.”

Berebichez added to Berlin's thought, noting that the relatively high number of women in the life sciences compared to other fields could be the result of selection bias – that is, more women might just be drawn to those areas. “We have to not just look at the absolute numbers,” she said, “but also the numbers relative to what women want.”

What if those differences between men and women and what women want are products of socialization well before adulthood, though? Wright said that in her own experience working with children, she's seen the effects of early gender differentiation. When kids start out in school, she said, the boys and girls would be split into two lines by gender. At first, both groups would be prone to pushing one another and playing around. By third grade, however, there was a big shift, with the girls being much more compliant.

Wright advocated for more intervention early on. “We have to educate girls to take more risks, as many as boys,” she said.

The panelists agreed that gender biases would continue to pervade the science community unless women – and men – actively combat them. However that's accomplished, Garbarino said the eventual goal should be to establish the perception that having women in science is normal.

“Just because we’re women doing science,” she said, “doesn’t mean we’re special.”

Comments