The CMS experiment, I remind you, is one of the four detectors which will start to measure the debris of proton-proton collisions at the Large Hadron Collider, in Geneva, when the latter starts operations a dozen weeks from now. The other three experiments are called Atlas, Alice, and LHCb. Atlas is a direct competitor of CMS in its high-energy discovery program, while Alice focuses on the collisions of heavy ions (which are planned for late 2010), and LHCb mainly studies forward physics in proton-proton collisions, aiming at precision B physics measurements. The poster is shown below, reduced to fit the page; if you click it you may download it in full size powerpoint format (but beware, it is a 8.5 Mb file). The figure on the top right frame in the poster illustrates the arrangement of the experimental facilities along the LHC tunnel under the border of France and Switzerland.

Two words on the plan

CMS will search the Higgs boson from day one, obviously. However, there are a couple of reasons why we do not expect to see it popping up very early on from our data: the reduced center-of-mass energy of the proton-proton collisions, which will only be half of the design 14 TeV for the first 10 months of running; and a somewhat reduced luminosity of the beams in the initial phase, with respect to earlier planning. Both these factors affect the discovery reach of CMS and Atlas.

When the energy of LHC startup was still under debate, eight months ago, CMS quickly produced estimates of the hit on the discovery reach that a reduced energy would take. On that occasion, sensitivity to the Standard Model Higgs boson achievable with 1 inverse femtobarn of collisions at 14 TeV and 10 TeV center-of-mass energy were compared. At the Chamonix meeting in February 2009 this information was debated and digested, and it was understood that it would be useless for discovery purposes to collect just a few inverse picobarns of data in 2009 and then face a long shutdown to perform those repairs which are required for ful-power running. The plan to run continuously through the winter, despite the large increase in electricity bills and the other logistic problems connected with neglecting Christmas holidays, arose back then.

Now that the plan has been finally settled to 7 TeV of c.m. energy, CMS has no revised estimates to show at conferences for the discovery reach at that energy. The 14 TeV case with one inverse femtobarn of data is still interesting, though: it shows the potential of the detector in a "reference" scenario. One can then eyeball that the same results take about four times more data to be obtained at 7 TeV c.m. energy. The assumption of 14 TeV and 1/fb of analyzed data is made in the studies included in the poster and described below.

Where is the Higgs ?

The Standard Model predicts that the Higgs boson is comparatively light. That information is due to its presence in virtual processes which might already have affected the observable value of quantities measured in electron-positron collisions by the LEP and SLC colliders, as well as to the top quark and W boson masses, now precisely measured by the Tevatron experiments.

A global fit recently updated to include summer 2009 results returns a curve of the "chisquared" as a function of the unknown Higgs mass: the larger the chisquared, the harder it is for measured electroweak data to get along with a particular Higgs mass value. The chisquared curve is shown in blue on the right: as you see, the minimum -the most likely value of the Higgs boson- lies at 87 GeV, with a 30ish GeV uncertainty. In other words, the Higgs boson cannot be very heavy, or there is something quite wrong in our understanding of its impact on the phenomenology of weak interactions. The chisquared would diverge, you see. Big deal ? Yes, big deal -a big chisquared in a global fit is like stench of rotten fish in a sushi bar.

A global fit recently updated to include summer 2009 results returns a curve of the "chisquared" as a function of the unknown Higgs mass: the larger the chisquared, the harder it is for measured electroweak data to get along with a particular Higgs mass value. The chisquared curve is shown in blue on the right: as you see, the minimum -the most likely value of the Higgs boson- lies at 87 GeV, with a 30ish GeV uncertainty. In other words, the Higgs boson cannot be very heavy, or there is something quite wrong in our understanding of its impact on the phenomenology of weak interactions. The chisquared would diverge, you see. Big deal ? Yes, big deal -a big chisquared in a global fit is like stench of rotten fish in a sushi bar. Then we also have direct limits (left): these come from LEP II -which in 2001 assessed that the Higgs cannot be much lighter than 114.4 GeV- and from the Tevatron -which recently determined that the mass range 160-170 GeV is disfavoured at 95% confidence level. Note, the LEP II bound is quite a bit stronger than the Tevatron one: the Higgs mass could indeed still be 165 GeV and nobody would raise a eyebrow, but if it was 110 GeV we would all fall off our chairs (and, as some commenter noted in the thread of the previous post, we would have to admit that a particular version of Supersymmetry which implies reduced Higgs-Z boson couplings is right on the money). In any case, since confidence levels have to be established before running experiments, physicists have agreed on 95% CL as their way to report the limits, and all we get is the information shown in the figure below: pink areas are "unfavoured". The black curve shows the Tevatron limit in units of the SM production rate of Higgs bosons: where the black curve gets below 1.0 there is an exclusion.

Then we also have direct limits (left): these come from LEP II -which in 2001 assessed that the Higgs cannot be much lighter than 114.4 GeV- and from the Tevatron -which recently determined that the mass range 160-170 GeV is disfavoured at 95% confidence level. Note, the LEP II bound is quite a bit stronger than the Tevatron one: the Higgs mass could indeed still be 165 GeV and nobody would raise a eyebrow, but if it was 110 GeV we would all fall off our chairs (and, as some commenter noted in the thread of the previous post, we would have to admit that a particular version of Supersymmetry which implies reduced Higgs-Z boson couplings is right on the money). In any case, since confidence levels have to be established before running experiments, physicists have agreed on 95% CL as their way to report the limits, and all we get is the information shown in the figure below: pink areas are "unfavoured". The black curve shows the Tevatron limit in units of the SM production rate of Higgs bosons: where the black curve gets below 1.0 there is an exclusion.To show you what I mean when I say that the two bounds have different strength, take then the Gfitter result shown below. The blue curve (or pick the green one if you are only confident in the simpler -2 ln Q method) is the outcome of putting together the result of direct searches with the electroweak indications in a global chisquared. This time, you see that there indeed is a brick wall on the left of 115 GeV -the chisquared literally blows below that value-, while there is just an upward bump in the region 160-170 GeV. Still, combining the direct and indirect information, that mass region is still unlikely by more than three standard deviations (see vertical scale on the right), which means you can bet against it.

All in all, evidence leads us to think that the Standard Model Higgs boson is light - probably between 115 and 140 GeV. In this region the search is difficult, because that particle is then too light to decay frequently to the golden signature of two vector bosons (WW or ZZ), and it needs to be searched in dirtier final states.

But we still look where we can...

A funny story has a drunken looking for his car keys under a street lamp at night. When asked where is he most likely to have lost them, he replies "Oh, I'm pretty sure I dropped 'em about a hundred feet down the road, but it's too dark to search them there". That is more or less what the CMS searches I present in my poster do: they provide information on the sensitivity to a Higgs boson in a range of masses which is disfavoured by indirect and direct searches, as I discussed above.

But things are not so clear-cut, in truth. We will still be able to see a 130 GeV Higgs boson in the H->WW and H->ZZ decay one day, but it might take a while. For advertising purposes, it is better to concentrate where we have a chance of doing better than the Tevatron experiments.

So in my poster I summarize the search for H->WW and H->ZZ events, as well as the search for

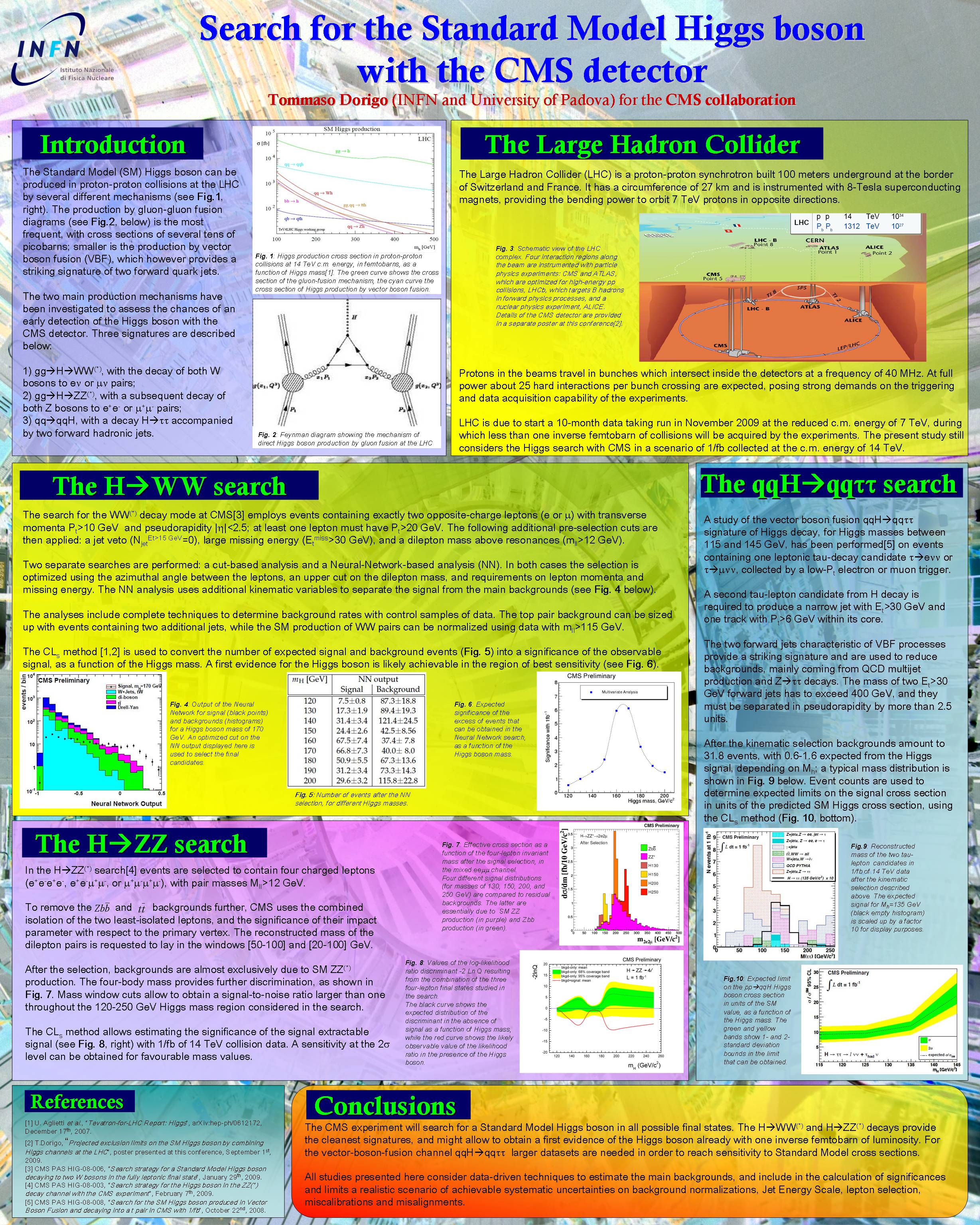

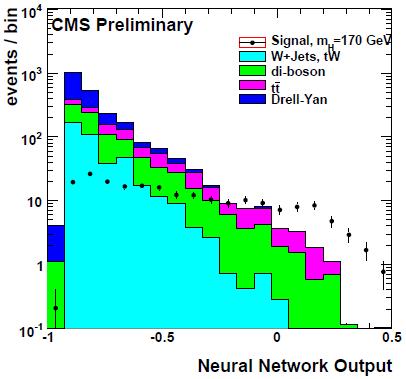

H->WW

When the Higgs decays to two W bosons, and each W decays into an electron-neutrino or muon-neutrino pair, the signature is rather clean: it includes two opposite-sign leptons of high momentum, large missing energy (from the two neutrinos) and no high-energy hadronic jets. Backgrounds come from direct production of two W bosons, which does occur in the Standard Model even in the absence of Higgs boson intervention, and from top pair production. A dedicated event selection can increase the relative size of the signal such that it exceeds backgrounds, if the Higgs mass is in a favourable region. A Neural Network classifier (NN) can use all the kinematic information available to measure in the events, and produce a good discrimination of the Higgs signal, as shown in the figure (the Higgs signal is shown by black points at high values of the NN output, the backgrounds are shown as stacked histograms).

When the Higgs decays to two W bosons, and each W decays into an electron-neutrino or muon-neutrino pair, the signature is rather clean: it includes two opposite-sign leptons of high momentum, large missing energy (from the two neutrinos) and no high-energy hadronic jets. Backgrounds come from direct production of two W bosons, which does occur in the Standard Model even in the absence of Higgs boson intervention, and from top pair production. A dedicated event selection can increase the relative size of the signal such that it exceeds backgrounds, if the Higgs mass is in a favourable region. A Neural Network classifier (NN) can use all the kinematic information available to measure in the events, and produce a good discrimination of the Higgs signal, as shown in the figure (the Higgs signal is shown by black points at high values of the NN output, the backgrounds are shown as stacked histograms).  An optimized search targeted in turn at the different mass hypotheses can produce an observation of the Higgs signal at better than 5-sigma significance in the most favourable mass range, as shown on the left. As noted above, this is however a region disfavoured by direct Tevatron searches, to the desperation of my colleague Michael Dittmar.

An optimized search targeted in turn at the different mass hypotheses can produce an observation of the Higgs signal at better than 5-sigma significance in the most favourable mass range, as shown on the left. As noted above, this is however a region disfavoured by direct Tevatron searches, to the desperation of my colleague Michael Dittmar.H->ZZ

When the Higgs decays to two Z bosons, the signature is amazingly clean: one may get four high-energy leptons, at least one pair of which makes the mass of the Z (he second pair is of lower effective mass if the Higgs has a mass below 180 GeV, because the corresponding Z boson is then a virtual particle, or as we say "off-mass-shell").

A simple event selection may lead to the distribution shown on the left, where four different Higgs mass signals are considered together for comparison (130, 150, 200, and 250 GeV, shown respectively in brown, yellow, orange, and red). The residual backgrounds, coming from direct ZZ production (they, too, can be created by non-Higgs SM processes), are also shown in pink. As you see, the signal sticks out prominently, but the vertical scale cools down our enthusiasm: we are talking about very few events if we consider one inverse femtobarn of collected data! Because of that, the extractable significance of the signal is less strong than the one achievable by the WW search in the mass range where the Higgs can be seen with relatively small amounts of data.

A simple event selection may lead to the distribution shown on the left, where four different Higgs mass signals are considered together for comparison (130, 150, 200, and 250 GeV, shown respectively in brown, yellow, orange, and red). The residual backgrounds, coming from direct ZZ production (they, too, can be created by non-Higgs SM processes), are also shown in pink. As you see, the signal sticks out prominently, but the vertical scale cools down our enthusiasm: we are talking about very few events if we consider one inverse femtobarn of collected data! Because of that, the extractable significance of the signal is less strong than the one achievable by the WW search in the mass range where the Higgs can be seen with relatively small amounts of data.H->tau tau

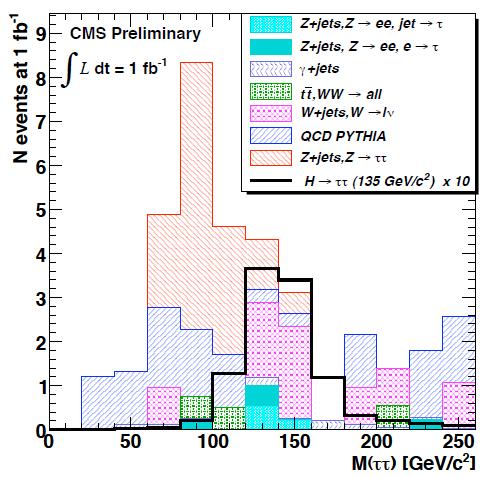

The third search I present is one for the process called "vector boson fusion", which is another way by which Higgs bosons may be produced at LHC. In vector boson fusion (VBF) diagrams two quarks from the protons spit out W or Z bosons, and it is the latter which fuse together to produce a Higgs. Because of that, the signature includes together with the Higgs two energetic quark jets emitted in forward and backward directions: these are the guys that radiated the vector bosons in the initial part of the reaction.

VBF production is interesting although tenfold more rare than the standard production of Higgs bosons, because the two forward jets effectively provide a means to distinguish the signal. A search for the Higgs decay to a pair of tau leptons, which is hard to distinguish from backgrounds otherwise, can then be carried out.

Even after a careful data selection, CMS is not expected to obtain a significant signal in this channel: the figure on the right shows the reconstructed tau-pair mass distribution for backgrounds (colored histograms) after all cuts, and the one expected for the signal in black, for a Higgs mass of 135 GeV. Alas, the latter histogram has been blown up by a factor of 10 for display purposes! In other words, one inverse femtobarn of data, even at 14 TeV, is insufficient to provide any indication of the Higgs boson in this channel.

Even after a careful data selection, CMS is not expected to obtain a significant signal in this channel: the figure on the right shows the reconstructed tau-pair mass distribution for backgrounds (colored histograms) after all cuts, and the one expected for the signal in black, for a Higgs mass of 135 GeV. Alas, the latter histogram has been blown up by a factor of 10 for display purposes! In other words, one inverse femtobarn of data, even at 14 TeV, is insufficient to provide any indication of the Higgs boson in this channel.Conclusions

In conclusion, CMS is a wonderful detector, and the LHC is the most powerful accelerator in the world (that is, will be such in two months), but one which still needs a lot of data to pinpoint rare processes such as Higgs boson production. If the Tevatron folks have been fooled by a downward fluctuation of backgrounds and the Higgs boson is indeed at 160 or 170 GeV, rest assured that CMS will see it with as little as few hundreds inverse picobarns of data; otherwise, we have to realize we are looking forward to a long and painful search in the forthcoming years.

In the next post I will show the other poster I am presenting at PIC 2009, the combination of the H->WW and H->ZZ channels and a comparison of 14 TeV and 10 TeV reaches. Stay tuned!

Comments