The possibility of human extinction in End of the World sci-fi is sometimes paired with a consideration of our next evolutionary step - a concept that is less scientific than it sounds (evolution shouldn't be considered in such linear terms), but one that does make an effective fictional tool for thinking about human impermanence.

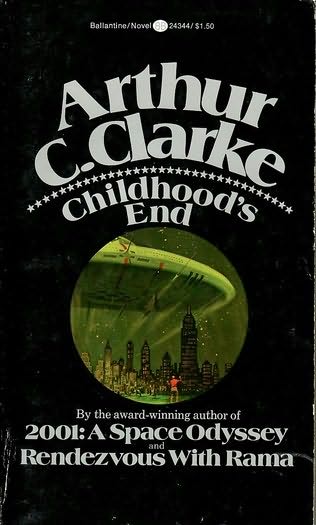

Arthur C. Clarke’s majestic Childhood’s End is about the end of Homo sapiens and evolutionary succession, in a sense. In this case the end of the human species doens't occur as a result of nuclear annihilation or an asteroid stike, and our evolutionary successors don't emerge from a struggling population of mutant survivors. The end here comes through a double transcendence. Our species leaves behind its childhood in a way that reveals our relationship to nature in its most universal form, and to science and rationality, which prove not only more powerful than our wildest imaginings, but also, paradoxically, small and limiting in the larger scheme.

The first step towards the end of humanity’s childhood comes in the form of an alien conquest, the arrival of the Overlords. One day out of the blue, the spaceships arrive, and the humanity’s days of independence and galactic isolation are over. Earth is ruled with the light, but irresistable touch of an alien species that possesses advanced technology which makes humanity's greatest scientific achievements seem almost meaningless. The aliens look like devils (complete with horns, red skin, and barbed tail) and are aptly termed by humans ‘The Overlords’. The Overlords’s apparent purpose is to guide the development of the world’s society into a utopia of scientific rationalism, something they claim to have achieved many times on many different planets.

The first step towards the end of humanity’s childhood comes in the form of an alien conquest, the arrival of the Overlords. One day out of the blue, the spaceships arrive, and the humanity’s days of independence and galactic isolation are over. Earth is ruled with the light, but irresistable touch of an alien species that possesses advanced technology which makes humanity's greatest scientific achievements seem almost meaningless. The aliens look like devils (complete with horns, red skin, and barbed tail) and are aptly termed by humans ‘The Overlords’. The Overlords’s apparent purpose is to guide the development of the world’s society into a utopia of scientific rationalism, something they claim to have achieved many times on many different planets.The Overlord supervisor Krallen, like the God of the Old Testament, appears omnipotent and omniscient (by virture of the Overlords’ technology). He operates in secret and never reveals himself directly, except to a single individual who hears Krallen's voice but never sees him. (That individual is the United Nations Secretary General - the Overlords simply co-opted the U.N. for their purposes. This book is John Bolton's worst nightmare.)

Under the Overlords’ guidance, both nature and human society are thoroughly controlled on scientific principles. There are no shortages, no place on Earth where humans can’t live, no crime, no poverty. It takes time, but essentially all of the worlds’ problems are solved, except perhaps one: human curiosity and restlessness. In this scientific uptopia, humanity falls into a state of homogeneity, and most creative endeavor stops. Scientific activity is pointless, because the Overlords, with technology that humans clearly will not be able to achieve in the near future, provide everything humans need to render their world tame. And tame it they do: it becomes fashionable to build luxury homes in the most inhospitablem exotic locations, just because its possible.

Yet humans' independent spirit will not be repressed - some are dissatisfied with the infantilization and dependency of the human species on the Overlords; they also suspect, rightly, that the Overlords have a secret agenda of their own - and how altruistic that agenda is, nobody can tell. However, that secret turns out to be something entirely different from what even the worst human pessimists expected, and, via an interesting plot twist, the human species in its current form ceases to exist by the end of the book.

Much of the 200-year time span in the book is about the development of Earth’s scientific uptopia. Clarke’s portrayal of this utopia is based on, ironically, a fundamental optimism common to many End of the World sci-fi novels of the 1950’s: the idea that human problems, both physical and societal, are fundamentally soluble through the dedicated application of rationality. In the development of the Overlord’s utopia, there are no trade-offs, no decisions that can’t be made rationally, no fundamental choices between two potentially rational choices. By focusing our scientific efforts only on the physical, we leave human problems unsolved and set ourselves up for destruction. The Overlord supervisor explains that humans would almost certainly have destroyed themselves without outside intervention. Thanks to the Overlords, nuclear war is averted and humanity conquers both nature and itself. Childhood has ended, and reason prevails.

Much of the 200-year time span in the book is about the development of Earth’s scientific uptopia. Clarke’s portrayal of this utopia is based on, ironically, a fundamental optimism common to many End of the World sci-fi novels of the 1950’s: the idea that human problems, both physical and societal, are fundamentally soluble through the dedicated application of rationality. In the development of the Overlord’s utopia, there are no trade-offs, no decisions that can’t be made rationally, no fundamental choices between two potentially rational choices. By focusing our scientific efforts only on the physical, we leave human problems unsolved and set ourselves up for destruction. The Overlord supervisor explains that humans would almost certainly have destroyed themselves without outside intervention. Thanks to the Overlords, nuclear war is averted and humanity conquers both nature and itself. Childhood has ended, and reason prevails.Yet the scientific utopia is only an adolescence, as it turns out. Humans, understandably, aren’t satisfied with being in a perpetual state of dependency, no matter how good life is under the Overlords. Many also lament the lack of creative artistic and scientific work, which appears to depend on having problems to struggle with. People are curious about the Overlords, who, although they show themselves physically, reveal little else about their own past to their human charges. Even with all of our physical and social problems solved, humans are still striving for something. The Overlord supervisor tells humans that they are under limits, that "the stars are not for man," but he's just igniting the fires of human curiosity. In the end, the last human being alive is the one who pushed against those limits and proved the Overlords wrong, at least in the case of one individual.

It is this striving, this drive to penetrate further into the mysteries of the universe that in Clarke's story proves to be a fundamental difference between humans and the Overlords. When one human being finally discovers more about the Overlords, it turns out that they, for all of their scientific achievements, are profoundly limited, and are doomed to never move on from the evolutionary plateau that they have reached.

It is this striving, this drive to penetrate further into the mysteries of the universe that in Clarke's story proves to be a fundamental difference between humans and the Overlords. When one human being finally discovers more about the Overlords, it turns out that they, for all of their scientific achievements, are profoundly limited, and are doomed to never move on from the evolutionary plateau that they have reached. Human restlessness turns out to be a result of a deeper potential, present in embryonic form through all human history until the very end of the book. This potential is also occasionally manifested in the form of paranormal abilities - something that Clarke confesses, in a 1990 foreword to the book, was something he believed there was good evidence for when he wrote the the book. (This confession somewhat soured the end of the book for me, I’ll admit.) With the help of the Overlords, humans transcended physical and social problems, but the true end of our species’ childhood is not something that is achieved through reason.

And thus in Childhood’s End, despite the tremendous power of science, the universe is not comprehensible through intelligence. The universe is intelligence, and ultimately to relate to the universe through science and rationality is to do so in a primitive and limited way. I found the connection to the paranormal a little hokey, but Clarke tells his story skillfully, helped by his ability to sketch characters of impressive depth depsite the large cast that moves through this 200-year story. This book is certainly a classic.

Next up in our post-apocalyptic survey: 1954, and a vampire holocaust with Richard Matheson's I am Legend.

Read the feed:

Comments