Nuclear waste is one of the biggest downsides to nuclear power, and can remain dangerous for hundreds of thousands of years. Geological disposal is often stated as the most preferable way of dealing with it, but what does it entail? What are the problems that need to be overcome, and how are governments going about overcoming them? Fortunately, most governments are trying to be transparent about the process, with thousands of reports available on the web.

For some coursework earlier this year, I looked at the subject from a geological point of view.

It would seem that mimicking nature would be among the easiest things to do for science. After all, it's right there, in front of us, happening for millions of years.

Take plants, for instance. Every day they absorb sunlight and turn it into energy but our solar technology is bordering on laughable and, if solar lobbyists get there way and it gets more subsidies and even mandates, criminal.

The issue science has is that the sun's rays are highly destructive to man-made materials and that leads to a gradual degradation of many systems developed to harness it.

Most fashion students keep finished designs in a wardrobe but Emily Crane has to use a freezer. Unlike the stereotypical fashion designer, Crane is more likely to be found in a lab coat and wearing goggles than working with pencils or scissors.

Crane’s work forms an exotic part of Kingston University’s display at Vauxhall Fashion Scout on September 17, during London Fashion Week, and she is currently preparing her collection but can’t promise what she’ll be showing - because it doesn't always work, being that her clothes are made of things like gelatin and seaweed.

The sharing, preservation and reuse of data has become an increasingly important element of modern scientific research, but even though granting agencies like the National Science Foundation (NSF) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) naturally embrace data sharing, resistance from parts of the scientific community has continued to block scientific progress and valuable research data over the world is kept under lock and key or hidden away in lab drawers, forcing time and cost of unnecessary duplication.

BMC Research Notes is commissioning a large, ongoing collection of educational articles which outline procedures for sharing data that enable the data to be readily re-used by others and providing researchers with best practice guidance.

Back to breathing the air of Fermilab after a full year away, I got to gauge a bit better the aftermath of the little incident created by

a posting of mine in July. As often happens with internet bubbles, they look quite dramatic as they inflate, but they leave no big scars. Two months have passed, and this looks like a good time to post here some ruminations about the general issue.

Physics Experiments And Confidentiality

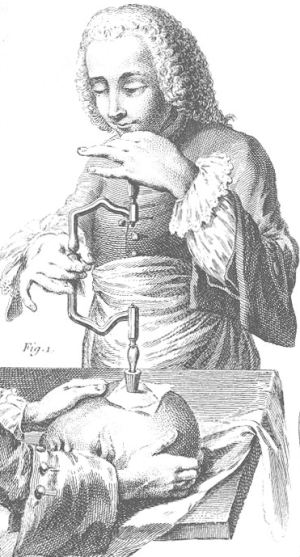

Today, trepanation, or drilling a hole in the head, is commonly used to release the pressure of swelling inside the skull.

Throughout history, it's been used to treat epilepsy, migraines, mood disorders and pretty much any other head condition that seemed to surgeons of the time as if it could be improved by seeing the light of day. But even more interesting than holding someone down and punching a hole through his/her skull is doing it yourself.

Recent estimates are that 7-11% of published research is 'open access', a term used to distinguish content that is open to other researchers and the public (free of charge to read) from research available only to subscribers of journals (called 'toll access' by open access advocates) and readers in libraries.

Today, trepanation, or drilling a hole in the head, is commonly used to release the pressure of swelling inside the skull.

Today, trepanation, or drilling a hole in the head, is commonly used to release the pressure of swelling inside the skull.