They wanted to see if numbers in our vision create “attentional biases” so volunteers were asked to identify the center of lines and squares filled with numbers. It showed how our perception of space is a complex interplay between “object-based” processing and our processing of numerical information.

This spatial-numerical association is evident in a left-to-right writing culture, where a simple game - having players press one of two buttons with the lower number on it - reveals faster response when the lower number is on the left; the opposite is true using larger numbers.

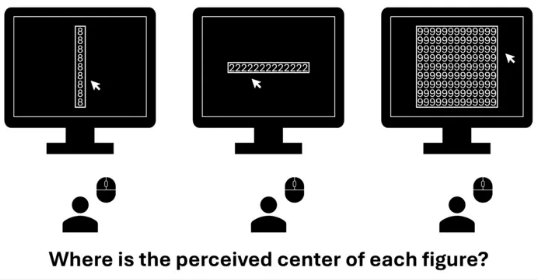

Bisection tasks reveal biases due to spatial-numerical association. The presence of numbers in the object acts to affect subtly participants’ perception of where the center is. Credit: Tokyo Metropolitan University

Yet the information does not need to be numbers, but something that indicates magnitude, like a brighter light, or louder noise. Similar trends have been seen in animals and insects, suggesting that a “mental number line,” some left-to-right mapping of magnitude-related information onto space, might be a deeply ingrained characteristic in nature.

A team of researchers from Tokyo Metropolitan University have been using “bisection tasks” to probe spatial-numerical association. Standard bisection tasks ask volunteers to estimate the center of a line or bar. When the bar is painted over with smaller numbers, they found that volunteers systematically put the center more left than for larger numbers. This confirms the left-to-right “mental number line” found in previous work. When they tried the same exercise with vertical bars, however, volunteers put their point lower for larger numbers, contrary to the “bottom-to-top” association expected from previous works. There is clearly more at work than just the mental number line.

In a new approach, the team proceeded to repeat the experiment with squares i.e. two-dimensional shapes. Curiously, they found that the effect of number magnitude disappeared. Instead, the presence of numbers was enough to induce a strong upward bias, and a weak leftward bias; an absence of numbers led to a stronger bias in the horizontal direction, likely due to pseudoneglect, a known natural bias in attention toward the left. The team propose that this vertical bias reflects the impact of the ventral visual stream, the part of our brain trying to recognize objects (in this case, numerical strings) which also tends to push attention upward. In this case, “object-based” processing seems to show a dominant effect over our processing of the value of numbers.

Citation: Hishiya, R., Ishihara, M. Numerically induced attentional biases in horizontal, vertical, and two-dimensional shapes. Sci Rep 15, 36819 (2025). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-21167-3

Comments