Like several other insect orders, the Lepidoptera is staggeringly diverse -- there are about 180,000 described species in the order and an untold number that remain unknown to biologists. (For comparison, there are about 5,000 mammal species).

Most people know the Lepidoptera ("leps" to entomologists) as moths and butterflies. The incompleteness of their taxonomic descriptions reflects their sheer diversity rather than academic neglect -- leps have been collected and studied for centuries. As it turns out, the distinction between moths and butterflies probably is not phylogenetically meaningful, as the "butterflies" (which includes three superfamilies: true butterflies, skipper butterflies, and moth-butterflies), though probably monophyletic as a group, may represent a clade nested within the other moths. However, I won't complain if these terms survive as they are useful in non-phylogenetic contexts.

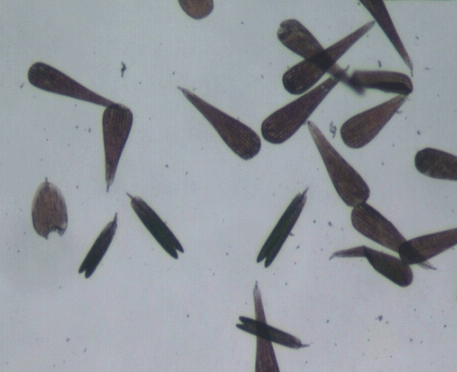

The name "Lepidoptera" means "scale wing" and, not surprisingly, refers to the fact that the wings of these insects are covered in tiny scales of various shapes and sizes:

Scales from the wing of the butterfly Anteos clorinde. Image by P. Pierossi.

Now, one might think that with so many species that have been studied for so long, we would have a relatively good handle on most aspects of lep biology. In the case of the size of their genomes, however, almost nothing is known. In fact, until a study conducted a few years ago, you could have counted the number of species that had been studied on one hand (Gregory and Hebert 2003).

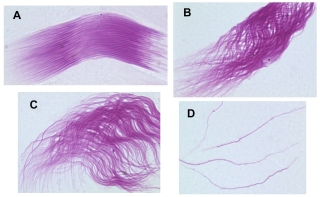

Still, we only analyzed 50 or so species. Part of the reason for the limited data on lep genome sizes is that they can be difficult to study. Collecting them is easy, but getting individual nuclei with a known number of genome copies is not. With many insects, working with spermatozoa is useful because you know they include one copy of the genome per nucleus. In moths and butterflies, however, the sperm form into tightly linked bundles of cells and isolating them can be challenging. In the first moth study, we dissected gonad tissue and mechanically separated the bundles of spermatozoa in chemicals meant to dissociate cell membranes. It worked enough to get data, but it was not simple.

Feulgen-stained spermatozoa from the moth Nepytia canosaria. Image from Gregory and Hebert (2003).

We have done the same sort of thing with butterflies, but again it proved difficult to get free nuclei. More recently, we have started a study of moths using flow cytometry, in which we can analyze nuclei from brain tissue rather than dealing with these gametes. This will let us cover hundreds of species in a matter of months. The procedure is that I collect moths at my trap at night, then bring them to the lab for processing in the morning. If we come across anything particularly intriguing, we can actually have an estimate of its genome size by the end of the day.

A light trap at my house.

For example, last week I came across this interesting fellow:

Photo by C. Kher.

This is Antheraea polyphemus, a giant silk moth in the family Saturniidae. It is named after the the cyclops Polyphemus of Greek mythology in reference to the large eye spot on each wing. It probably isn't visible from this picture (taken with a camera phone), but the four whitish spots are actually transparent because they are devoid of scales.

We had previously analyzed the genome size of another large saturniid, indeed the largest moth in the world, the Atlas moth Attacus atlas. Unlike Antheraea, Attacus is not found in the wild in southern Ontario, and we "collected" it at a butterfly conservatory.

Photo by the author.

Insect genomes differ considerably in size. The largest currently listed is found in a grasshopper and is about 5 times larger than the human genome. Moths and butterflies are more constrained (the working hypothesis is that this is because larger genomes are associated with slow cell divisions such that metamorphosis imposes a limitation). Still, we wondered whether species with large bodies might have large genomes, as has been seen in some other groups of animals.

The answer is no. Both of these huge moths have genomes around average for moths. There may still be interesting patterns in genome size variation among moths, but we will have to wait for additional data.

And so, tonight I will once again walk down to the light trap and collect the moths -- large and small -- and bring them in to our lab for analysis.

Comments