The largest of these undersea Ice Age domes lies at a depth of 700 feet (220 meters), too deep for scuba diving, which explains why the volcanoes have never before been spotted by humans. The discovery is documented this week in Nature Geoscience.

"They're larger than a football-field-long and as tall as a six-story building," says David Valentine, a geoscientist at University of California, Santa Barbara. "They're massive features, and are made completely out of asphalt."

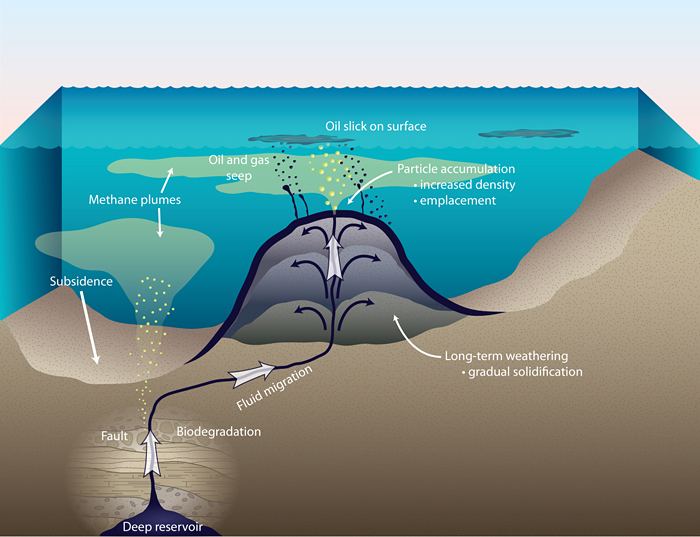

Schematic diagram highlighting the formation of an asphalt volcano and the associated release of oil and methane to the surrounding environment.

(Illustration by Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Researchers first viewed the volcanoes during a 2007 dive on the research submersible Alvin. Using the sub's robotic arm, the researchers broke off samples and brought them to labs at UCSB and WHOI for testing.

In 2009, the team made two more dives to the area in Alvin. They also conducted a detailed survey of the area using an autonomous underwater vehicle, Sentry, which takes photos as it glides about nine feet above the ocean floor.

"When you 'fly' Sentry over the sea floor, you can see all of the cracking of the asphalt and flow features," says Valentine. "All the textures are visible of a once-flowing liquid that has solidified in place. "That's one of the reasons we're calling them volcanoes, because they have so many features that are indicative of a lava flow."

Tests showed that these aren't your typical lava volcanoes, however, found in Hawaii and elsewhere around the Pacific Rim.

Using a mass spectrometer, carbon dating, microscopic fossils, and comprehensive, two-dimensional gas chromatography, the scientists determined that the structures are asphalt. They were formed when petroleum flowed from the sea-floor about 30,000-40,000 years ago.

Chris Reddy, a scientist at WHOI and a co-author of the paper, says that "the volcanoes underscore a little-known fact: half the oil that enters the coastal environment is from natural oil seeps like the ones off the coast of California."

The researchers also determined that the volcanoes were at one time a prolific source of methane.

The two largest volcanoes are about a kilometer apart and have pits or depressions surrounding them. These pits, according to Valentine, are signs of "methane gas bubbling from the sub-surface." That's not surprising, he says, considering how much petroleum was flowing there in the past. "They were spewing out a lot of petroleum, but also lots of natural gas," he says, "which you tend to get when you have petroleum seepage in this area."

The discovery that vast amounts of methane once emanated from the volcanoes caused the scientists to wonder if there might have been an environmental impact on the area during the Ice Age. "It became a dead zone," says Valentine. "We're hypothesizing that these features may have been a major contributor to those events."

While the volcanoes have been dormant for thousands of years, the 2009 Alvin dive revealed a few spots where gas was still bubbling.

"We think it's residual gas," says Valentine, who added that the amount of gas is so small it's harmless, and never reaches the surface.

Citation: David L. Valentine et al., 'Asphalt volcanoes as a potential source of methane to late Pleistocene coastal waters', Nature Geoscience, April 2010; doi:10.1038/ngeo848 Letter

Comments