The hypothetical drug would target and fix the point irregularities which have accumulated over time that can lead to the formation of tumors — and cancer.

"Personalized cancer drug delivery? Depending on the approach, it could be as soon as 10 to 15 years away," says Viterbi professor Andrea Armani , an assistant professor of the Mork Family Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science.

Armani has received the NIH's 2010 New Innovator Award, a $2.3 million research grant over five years to investigate epigenetics and study changes in DNA which are associated with cancer.

Analysis of these DNA changes has shown promise in the early detection and treatment of ovarian and other types of cancer, says Armani, but current research methods are only able to capture snapshots of these DNA changes, instead of monitoring the process continuously. Therefore, they miss information that could be vital to understanding processes that have been linked to cancer and other diseases, like Huntington's and diabetes.

The sensitivity or resolution of many of these techniques is also very poor. "It's like trying to watch a TV show through static," says Armani.

She believes her method will push the field from static straight to HDTV. The proposal is to develop an ultrasensitive nanolaser that would allow her to detect changes in DNA as they're happening...in real-time. This device will also allow her to study a single DNA strand in isolation, rather than groups of hundreds to thousands of strands as researchers must do with current technology.

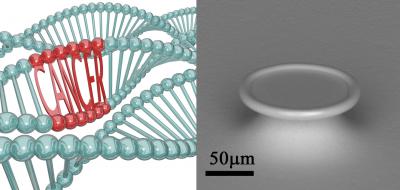

In the DNA rendering to the left, two of the three strands of DNA are normal but the third strand has a region which can cause cancer. Armani's research is focused on detecting these regions and understanding what events trigger the change in the DNA. The technique that she is using relies on a very sensitive nanolaser device which is the 'ring' looking object shown in the electron microscope image to the right. The laser shown in this picture is smaller than the width of a human hair. Credit: USC Viterbi School of Engineering.

As DNA binds to the surface of the nanolaser, the "color" or lasing wavelength emitted by the laser will change. As the DNA changes, the color will change again. The improved resolution is a result of the precision with which the color can be monitored.

The first part of the project focuses on building the nanolaser instrument, while the second half funds the DNA experiments. The goal? What Armani calls "un-doing" these triggers that can cause cancer.

She will focus first on using the nanolaser to perform initial proof-of-concept experiments using known triggers, such high concentrations of common solvents and cleaning agents.

Part of this process involves taking a single strand of DNA, exposing it to a harsh chemical and seeing whether a specific change is initiated. Ultimately she'd like to be able to warn people which triggers to avoid.

Comments