The epidemic affected 445 people in the city of Pointe-Noire, the economic capital of the country, killing almost half of them. The researchers fear the emergence of other strains against which vaccines would have little effect.

The global initiative to eradicate poliomyelitis through routine vaccination has helped reduce the number of cases by more than 99% in 30 years, from an estimated 350,000 cases in 1988 to 650 reported cases in 2011. Epidemics still occur, such as the ones in the Republic of the Congo in 2010, Tajikistan in 2010, and China in 2011. The epidemic outbreak in 2010 in the Republic of the Congo differed from the others in its exceptionally high mortality rate of 47%: out of the 445 confirmed cases, nearly 210 died. The researchers first attributed the seriousness of the epidemic to low vaccine coverage.

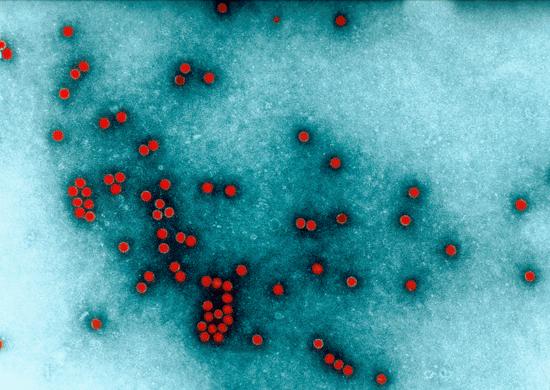

Poliovirus. © Institut Pasteur / C. Dauguet

The cause was something completely different, according to researchers who identified the virus responsible and sequenced its DNA. The DNA sequence shows two mutations, unknown until now, of the proteins that form the "shell" (capsid) of the virus. On the face of it, this evolution complicates the task for the antibodies produced by the immune system of the vaccinated patient as they can no longer recognise the viral strain.

The researchers then tested the resistance of this variant of poliovirus on blood samples from more than 60 vaccinated people, including volunteers living in neighboring Gabon, where part of the research team was based, and German medical students. Their antibodies were shown to be less effective against the Congo strain than against the other strains of poliovirus. The researchers estimate that 15%–30% of these people would not have been protected during the 2010 epidemic.

At a time when the global campaign to eradicate poliomyelitis is entering its final phase, researchers fear that other variants of the virus may emerge among populations immunised with the vaccine. Undoubtedly, these strains are circulating in nature.

While quite rare, they could lead to fatal epidemics such as the one in 2010 in the Republic of the Congo if they reach areas where the more common strains have been eradicated, but where vaccine coverage is insufficient. The researchers are calling for better clinical and environmental monitoring to completely wipe out the scourge of polio.

References:

DREXLER J.F., GRARD G., LUKASHEV A.N., KOZLOVSKAYA L.I., BÖTTCHER S., USLU G., REIMERINK J., GMYL A.P., TATY-TATY R., LEKANA-DOUKI S.E., NKOGHE D., EIS-HÜBINGER A.M., DIEDRICH S., KOOPMANS M., LEROY E.M., DROSTEN C. Robustness against serum neutralization of a poliovirus type 1 from a lethal epidemic of poliomyelitis in the Republic of Congo in 2010. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014, vol. 111 no. 35, 12889–12894, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323502111

GRARD G., DREXLER J. F., LEKANA-DOUKI S., CARON M., LUKASHEV A., NKOGHE D., GONZALEZ JEAN-PAUL, DROSTEN C., LEROY ERIC. Type 1 wild poliovirus and putative enterovirus 109 in an outbreak of acute flaccid paralysis in Congo, October-November 2010. Eurosurveillance, 2010, 15 (47), p. 6-8. ISSN 1560-7917 fdi:010052948

Comments