A team of scientists led by Carnegie Museum of Natural History paleontologist Zhe-Xi Luo describes in Nature Juramaia sinensis, a small shrew-like mammal that lived in China 160 million years ago during the Jurassic period. Juramaia is the earliest known fossil of eutherians, the group that evolved to include all placental mammals, which provide nourishment to unborn young via a placenta.

As the earliest known fossil ancestral to placental mammals, Juramaia provides fossil evidence of the date when eutherian mammals diverged from other mammals, metatherians (whose descendants include marsupials like kangaroos) and monotremes (like the platypus). As Luo explains, "Juramaia, from 160 million years ago, is either a great-grand-aunt, or a 'great-grandmother' of all placental mammals that are thriving today."

New Jurassic eutherian mammal Juramaia sinensis. The original fossil (type specimen) is preserved on a shale slab from the Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation. The fossil belongs to the Beijing Museum of Natural History (BMNH PM1143) and is being jointly studied by Chinese and American scientists. “Jura” represents the Jurassic Period of the geological time scale while “-maia” means “mother” and sinensis means “from China” so the the full name means “Jurassic mother from China.” Photo: Zhe-Xi Luo/Carnegie Museum of Natural History

The fossil of Juramaia sinensis was discovered in the Liaoning Province in northeast China and examined by Luo and collaborators Chong-Xi Yuan and Qiang Ji, from the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, and Qing-Jin Meng from the Beijing Museum of Natural History, where the fossil is stored. The Juramaia sinensis fossil has an incomplete skull, part of the skeleton and impressions of residual soft tissues such as hair. Most importantly, Juramaia's complete teeth and forepaw bones enable paleontologists to pin-point that it is closer to living placentals on the mammalian family tree than to the pouched marsupials, such as kangaroos.

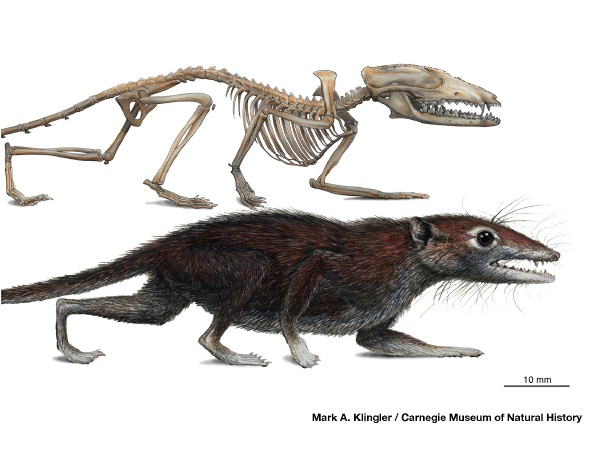

Skeletal and fur reconstructions of the Jurassic eutherian Juramaia sinensis. The new Jurassic mammal Juramaia is a shrew-sized mammal with a skull 22 mm long (just over 3/4 of an inch). It weighed around 15 grams (about half an ounce), fed on insects and worms, and had a great ability to climb. Artwork by Mark A. Klingler of Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Resetting the evolutionary clock

"Understanding the beginning point of placentals is a crucial issue in the study of all mammalian evolution," says Luo. The date of an evolutionary divergence—when an ancestor species splits into two descendant lineages—is among the most important pieces of information an evolutionary scientist can have. Modern molecular studies, such as DNA-based methods, can calculate the timing of evolution by a "molecular clock." But the molecular clock needs to be cross-checked and tested by the fossil record. Prior to the discovery of Juramaia, the divergence point of eutherians from metatherians posed a quandary for evolutionary historians: DNA evidence suggested that eutherians should have shown up earlier in the fossil record—around 160 million years ago.

The oldest known eutherian was Eomaia (originally described in 2002 by a team of scientists led by Zhe-Xi Luo and Carnegie mammalogist John Wible) dated 125 million years ago. The discovery of Juramaia gives much earlier fossil evidence to corroborate the DNA findings, filling an important gap in the fossil record of early mammal evolution and helping to establish a new milestone of evolutionary history.

Juramaia also reveals adaptive features that may have helped the eutherian newcomers to survive in a tough Jurassic environment. Juramaia's forelimbs are adapted for climbing; since the majority of the Jurassic mammals lived exclusively on the ground, the ability to escape to the trees and explore the canopy might have allowed eutherian mammals to exploit an untapped niche.

Luo supports this perspective: "The divergence of eutherian mammals from marsupials eventually led to placental birth and reproduction that are so crucial for the evolutionary success of placentals. But it is their early adaptation to exploit niches on the tree that paved their way toward this success."

Read more on Juramaia sinensis at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Citation: Zhe-Xi Luo, Chong-Xi Yuan, Qing-Jin Meng&Qiang Ji, 'A Jurassic eutherian mammal and divergence of marsupials and placentals', Nature 476, 442–445 (25 August 2011) doi:10.1038/nature10291

Comments