Temperature allows us to make a simple statistical statement about the energy of particles without having to know the specific details of the system.

Temperature allows us to make a simple statistical statement about the energy of particles without having to know the specific details of the system. How do quantum particles reach a state where statistical statements are possible? The result is surprising: a cloud of atoms can actually have several temperatures at once.

Scientists from the Vienna University of Technology together with colleagues from Heidelberg University note that the air around us consists of countless molecules, moving around randomly. It would be impossible to track them all and to describe all their trajectories but in most cases that is not necessary. Properties of the gas can be found which describe the collective behaviour of all the molecules, such as the air pressure or the temperature, which results from the particles' energy.

On a hot summer's day, the molecules move at about 430 meters per second, in winter, it is a bit less.

This statistical view developed by Ludwig Boltzmann has proved to be extremely successful and describes many different physical systems, from pots of boiling water to phase transitions in liquid crystals in LCD-displays. However, in spite of huge efforts, open questions have remained, especially with regard to quantum systems. How the well-known laws of statistical physics emerge from many small quantum parts of a system remains one of the big open questions in physics.

Hot and Cold at the Same Time

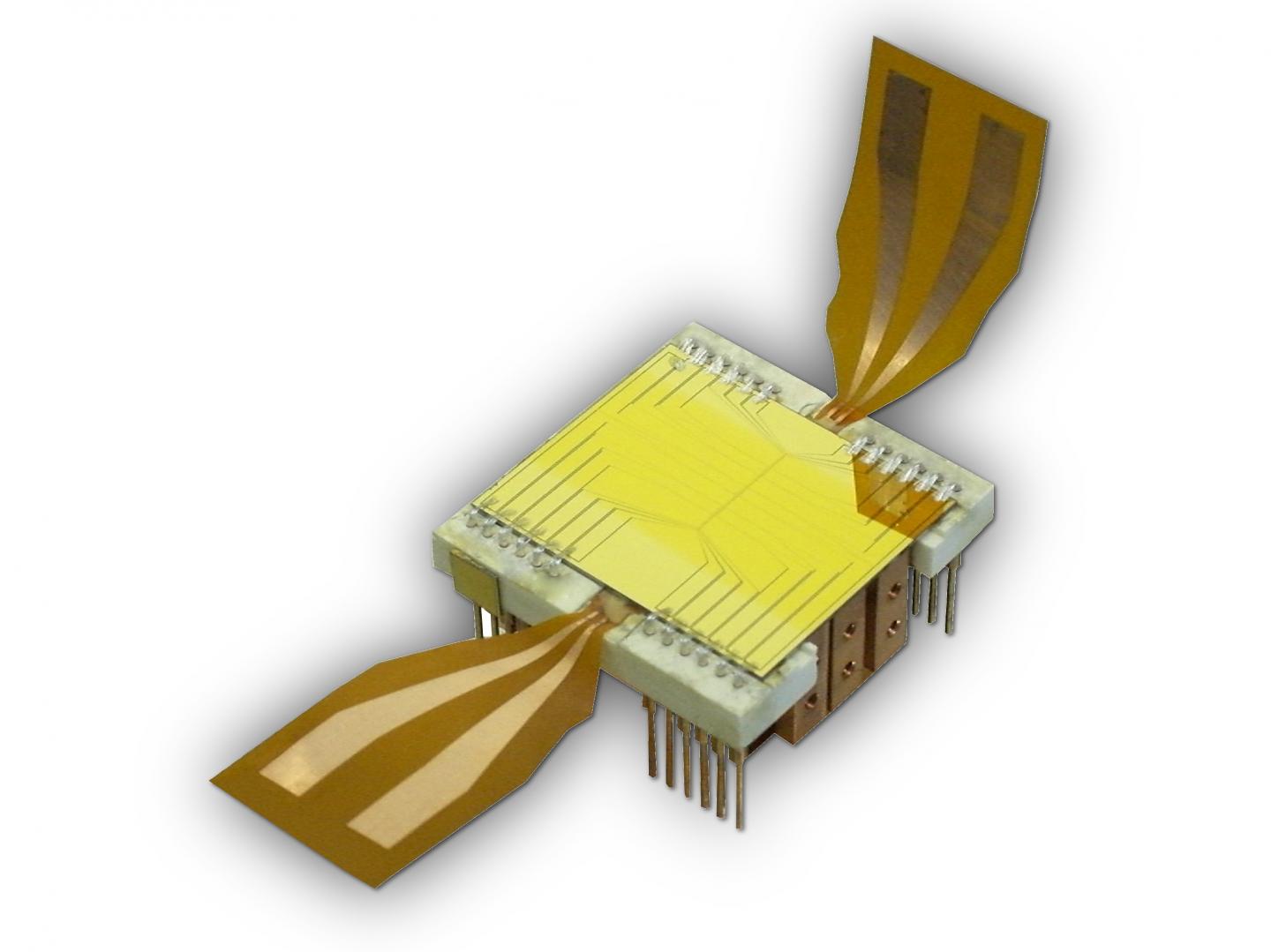

In a new study, scientists succeeded in studying the behavior of a quantum physical multi-particle system in order to understand the emergence of statistical properties. The team of Professor Jörg Schmiedmayer used a special kind of microchip to catch a cloud of several thousand atoms and cool them close to absolute zero at -273°C, where their quantum properties become visible.

The experiment showed remarkable results: When the external conditions on the chip were changed abruptly, the quantum gas could take on different temperatures at once. It can be hot and cold at the same time. The number of temperatures depends on how exactly the scientists manipulate the gas. "With our microchip we can control the complex quantum systems very well and measure their behaviour", says Tim Langen, leading author of the paper published in "Science". There had already been theoretical calculations predicting this effect, but it has never been possible to observe it and to produce it in a controlled environment.

The experiment helps scientists to understand the fundamental laws of quantum physics and their relationship with the statistical laws of thermodynamics. This is relevant for many different quantum systems, maybe even for technological applications. Finally, the results shed some light on the way our classical macroscopic world emerges from the strange world of tiny quantum objects.

Preprint: T. Langen et al., Experimental observation of a generalized Gibbs ensemble, arXiv:1411.7185. Top image: the atom chip for capturing and cooling clouds of atoms. Credit: TU Wien

Comments