Scholars surveying almost 11,000 drug users at 150 drug-treatment facilities in 48 states found that an abuse-deterrent formulation of the prescription drug OxyContin was successful in getting abusers and addicts to stop using the drug, but only to a point - and then others switched to something else anyway.

Not much we can do after that, society has done their part, the manufacturer has done their part, and the survey also showed people abusing OxyContin were doing lots of other things.

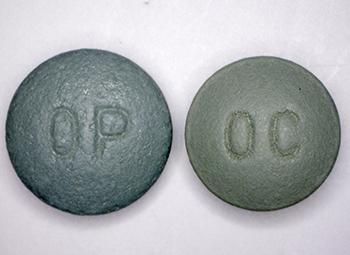

OxyContin comes in several different dosages, including this 80 mg version. An abuse-deterrent formulation of the OxyContin (left), introduced in 2010, has curtailed its illicit use, but about 25 percent of drug abusers entering rehab still abuse the drug. Credit: US Drug Enforcement Administration

The original formulation of OxyContin contained high levels of the pain-killing drug oxycodone so that small amounts of the drug could be released over a long period of time. However, abusers learned they could crush the pills and snort the powder or dissolve the pills in liquid and then inject it.

Clever junkies are also why it is so hard to find good cold medicine today.

To discourage abuse, the newer formulation of OxyContin, introduced in 2010 was designed to make it harder to crush or dissolve the pills. And it worked. Two years later, the percentage of those who got high with the abuse-deterrent form of the drug in the month before entering a treatment center had fallen to 26 percent, down from 45 percent. Almost half of the drug abusers surveyed in 2014 reported they had also used heroin in the 30 days before they entered treatment.

"We found that the abuse-deterrent formulation was useful as a first line of defense," said senior investigator Theodore J. Cicero, PhD, a professor of neuropharmacology in psychiatry. "OxyContin abuse in people seeking treatment declined, but that decline slowed after a while. And during that same time period, heroin use increased dramatically."

In other words, by making a clinically tested drug harder to use for junkies, we sent them toward unsafe drugs. 70 percent started using heroin instead. Many said they made that switch for economic reasons.

Advocates are now blaming the manufacturer for making their product harder to misuse.

"A few years ago when we did interviews with people in treatment, many would tell us that although they were addicts, at least they weren't using heroin," Cicero said. "But now, many tell us that a prescription opioid might run $20 to $30 per tablet while heroin might only cost about $10."

Limiting access to a prescription drug by making it harder to abuse does not change the demand side of the drug abuse equation, he said. People who want to get high find ways to continue doing so.

"The newer formulations are less attractive to abusers, but the reality is -- and our data demonstrate this quite clearly -- it's naïve to think that by making an abuse-deterrent pill we can eliminate drug abuse," he said. "There are people who will continue to use, no matter what the drug makers do, and until we focus more on why people use these drugs, we won't be able to solve this problem."

The data were collected as part of the SKIP (Survey of Key Informants' Patients) program, a component of the RADARS (Researched Abuse, Diversion and Addiction-Related Surveillance) system, funded through an unrestricted research grant sponsored by the Denver Health and Hospital Authority, which collects subscription fees from 14 pharmaceutical firms. The researchers also were supported by private university funds.

Cicero TJ, Ellis MS. Abuse-deterrent formulations and the prescription opioid abuse epidemic in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry, published online March 11, 2015. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3043

Comments