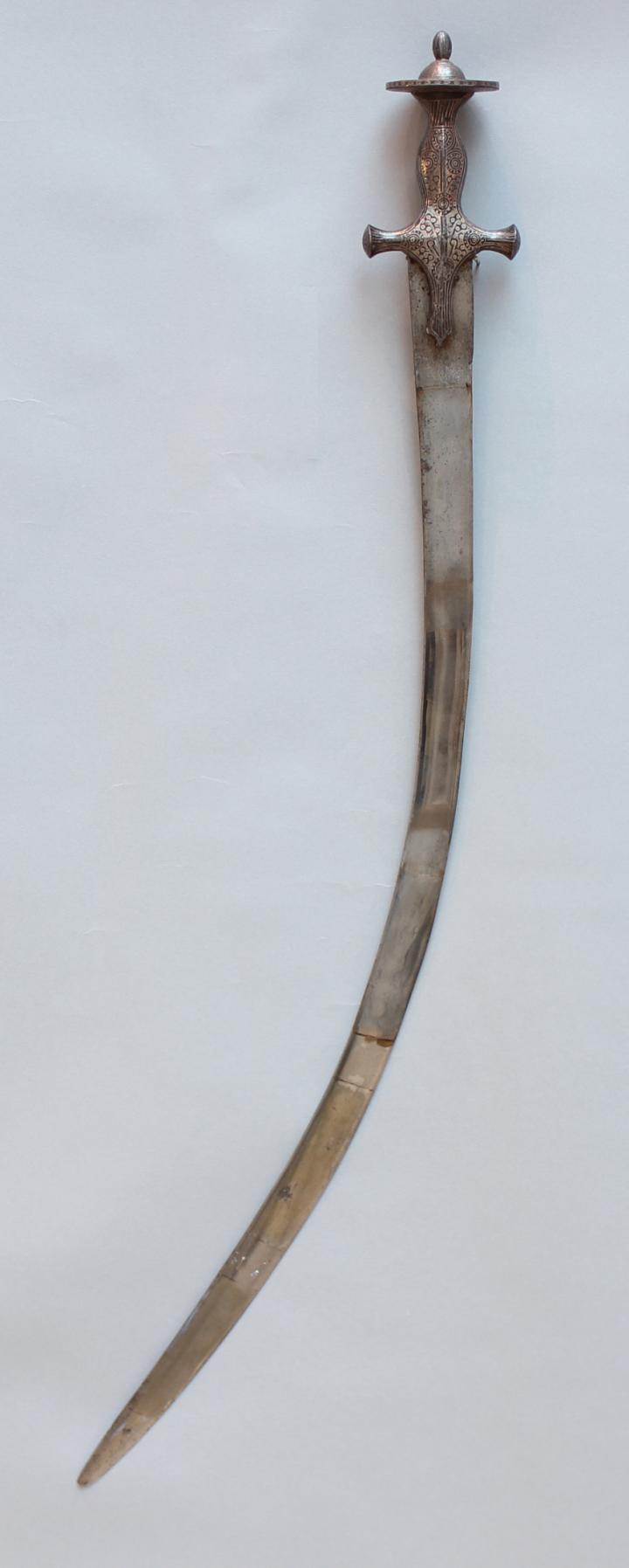

The study, led by Eliza Barzagli of the Institute for Complex Systems and the University of Florence in Italy, used metallography and neutron diffraction to test the differences and complementarities of the two techniques. The shamsheer was made in India in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century and is of Persian origin. The base design spread across Asia and eventually gave rise to the family of similar weapons called scimitars that were forged in various Southeast Asian countries.

Credit: Dr. Alan Williams/Wallace Collection

The sword in question first underwent metallographic tests at the laboratories of the Wallace Collection to ascertain its composition. Samples to be viewed under the microscope were collected from already damaged sections of the weapon. The sword was then sent to the ISIS pulsed spallation neutron source at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in the UK. Two non-invasive neutron diffraction techniques not damaging to artefacts were used to further shed light on the processes and materials behind its forging.

"Ancient objects are scarce, and the most interesting ones are usually in an excellent state of conservation. Because it is unthinkable to apply techniques with a destructive approach, neutron diffraction techniques provide an ideal solution to characterize archaeological specimens made from metal when we cannot or do not want to sample the object," said Barzagli, explaining why different methods were used.

It was established that the steel used is quite pure. Its high carbon content of at least one percent shows it is made of wootz steel. This type of crucible steel was historically used in India and Central Asia to make high-quality swords and other prestige objects. Its band-like pattern is caused when a mixture of iron and carbon crystalizes into cementite. This forms when craftsmen allow cast pieces of metal (called ingots) to cool down very slowly, before being forged carefully at low temperatures. Barzagli's team reckons that the craftsman of this particular sword allowed the blade to cool in the air, rather than plunging it into a liquid of some sort. Results explaining the item's composition also lead the researchers to presume that the particular sword was probably used in battle.

Craftsmen often enhanced the characteristic "watered silk" pattern of wootz steel by doing micro-etching on the surface. Barzagli explains that through overcleaning some of these original 'watered' surfaces have since been obscured, or removed entirely. "A non-destructive method able to identify which of the shiny surface blades are actually of wootz steel is very welcome from a conservative point of view," she added.

Citation: Barzagli E. et al (2015). Characterization of an Indian sword: classic and noninvasive methods of investigation in comparison, Applied Physics A - Materials Science&Processing. DOI 10.1007/s00339-014-8968-0

Comments