In January of 2012, a new X-ray source flared and rapidly brightened in the Andromeda galaxy (M31), l2.5 million light-years from earth. The event was classified as an ultraluminous X-ray source (ULX), the second ever seen in M31 and efforts with X-ray telescopes and radio observatories resulted in the first detection of radio-emitting jets from a stellar-mass black hole outside our own galaxy.

A ULX is thought to be a binary system containing a black hole that is rapidly accreting gas from its stellar companion. To account for the high-energy output, gas must be flowing into the black hole at a rate very near a theoretical maximum - which astronomers do not yet fully understand.

As gas spirals toward a black hole, it becomes compressed and heated, eventually reaching temperatures where it emits X-rays. As the rate of matter ingested by the black hole increases, so does the X-ray brightness of the gas. At some point, the X-ray emission becomes so intense that it pushes back on the inflowing gas, theoretically capping any further increase in the black hole's accretion rate. Astronomers refer to this as the Eddington limit, after Sir Arthur Eddington, the British astrophysicist who first recognized a similar cutoff to the maximum luminosity of a star.

"Black-hole binaries in our galaxy that show accretion at the Eddington limit also exhibit powerful radio-emitting jets that move near the speed of light," said Matthew Middleton, an astronomer at the Anton Pannekoek Astronomical Institute in Amsterdam. "There are four black hole binaries within our own galaxy that have been observed accreting at these extreme rates. Gas and dust in our own galaxy interfere with our ability to probe how matter flows into ULXs, so our best glimpse of these processes comes from sources located out of the plane of our galaxy, such as those in M31."

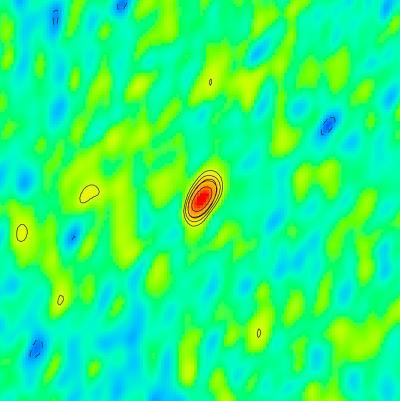

The ULX's radio-emitting jet (center) is unresolved in this image constructed from Very Long Baseline Array data. Each side of the image is 20 milliarcseconds across, or about the width of a human hair seen from a distance of half a mile. Credit: NRAO/M. Middleton et al.

Although astronomers know little about the physical nature of these jets, detecting them at all would confirm that the ULX is accreting at the limit and identify it as a stellar mass black hole.

The XMM-Newton observatory first detected this ULX, named XMMU J004243.6+412519 after its astronomical coordinates, on Jan. 15th. Then an international team began monitoring it at X-ray energies using XMM-Newton and the Swift satellite and Chandra X-ray Observatory. The scientists conducted radio observations using the Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) and the continent-spanning Very Long Baseline Array, in Socorro, N.M., and the Arcminute Microkelvin Imager Large Array located at the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory near Cambridge, England.

They note detection of intense radio emission associated with a jet moving at more than 85 percent the speed of light. VLA data reveal that the radio emission was quite variable, in one instance decreasing by a factor of two in just half an hour.

"This tells us that the region producing radio waves is extremely small in size -- no farther across than the distance between Jupiter and the sun," explained team member James Miller-Jones, a research fellow at the Curtin University node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research in Perth, Western Australia.

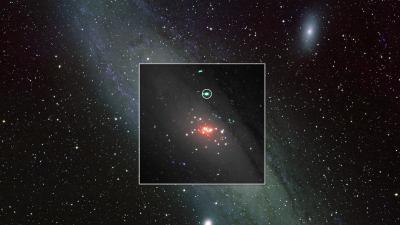

This image composites XMM-Newton X-ray data onto an optical view of the Andromeda galaxy; the ULX is circled. Colors in the XMM image correspond to different X-ray energies: 0.2 to 1 keV (red), 1 to 2 keV (green) and 2 to 4.5 keV (blue). Credit: Background: Bill Schoening, Vanessa Harvey/REU program/NOAO/AURA/NSF;Inset: ESA/M. Middleton et al.

Black holes have been conclusively detected in two varieties: "lightweight" ones created by stars and containing up to a few dozen times the sun's mass, and supermassive "heavyweights" of millions to billions of solar masses found at the centers of most big galaxies. Astronomers have debated whether many ULXs represent hard-to-find "middleweight" versions, containing hundreds to thousands of solar masses.

"The discovery of jets tells us that this particular ULX is a typical stellar remnant about 10 times the mass of the sun, swallowing as much material as it possibly can," Middleton said. "We may well find jets in ULXs with similar X-ray properties in other nearby galaxies, which will help us better understand the nature of these incredible outflows."

Commenting on the findings on behalf of the Swift team, Stefan Immler at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., noted that it was almost exciting enough for astronomers to witness a new ULX so close to home, even if "close" is a few million light-years away. "But detecting the jets is a real triumph, one that will allow us to study the accretion process of these elusive black hole candidates in never-before-seen detail," he said.

Published in Nature.

Comments