It used to be that El Nino was a predictable phenomenon that explained odd weather changes but recent global warming studies minimized its impact - everything was global warming instead. Now, it seems, El Nino is back in atmospheric fashion.

Scientists have known about El Niño weather fluctuations over a large portion of the world since the early 1950s. They occur in cycles every three to seven years, changing rain patterns that can trigger flooding as well as drought.

Siegfried Schubert of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., and his colleagues studied the impact that El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events have on the most intense U.S. winter storms and now believe that some of the most intense winter storm activity over parts of the United States are set in motion by those changes in the Pacific Ocean.

The scientists examined daily records of snow and rainfall events over 49 U.S. winters, from 1949-1997, together with results from computer model simulations. According to Schubert, the distant temperature fluctuations in Pacific Ocean surface waters near the equator are likely responsible for many of the year-to-year changes in the occurrence of the most intense wintertime storms.

"By studying the history of individual storms, we've made connections between changes in precipitation in the U.S. and ENSO events in the Pacific," said Schubert, a meteorologist and lead author of the study. "We can say that there is an increase in the probability that a severe winter storm will affect regions of the U.S. if there is an El Niño event."

"Looking at the link between large-scale changes in climate and severe weather systems is an emerging area in climate research that affects people and resources all over the world," said Schubert. "Researchers in the past have tended to look at changes in local rainfall and snow statistics and not make the connections to related changes in the broader storm systems and the links to far away sources. We found that our models are now able to mimic the changes in the storms that occurred over the last half century. That can help us understand the reasons for those changes, as well as improve our estimates of the likelihood that stronger storms will occur."

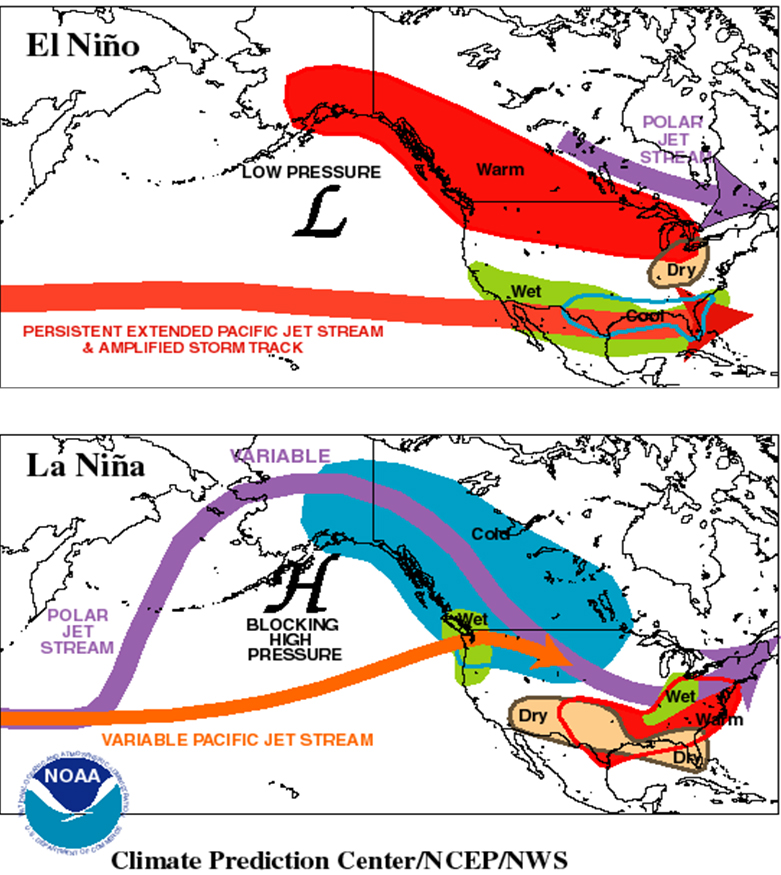

An ENSO episode typically consists of an El Niño phase followed by a La Niña phase. During the El Niño phase, eastern Pacific temperatures near the equator are warmer than normal, while during the La Niña phase the same waters are colder than normal. These fluctuations in Pacific Ocean temperatures are accompanied with fluctuations in air pressure known as the Southern Oscillation.

ENSO is a coupled ocean-atmosphere effect that has a sweeping influence on weather around the world. Scientists found that during El Niño winters, the position of the jet stream is altered from its normal position and, in the U.S., storm activity tends to be more intense in several regions: the West Coast, Gulf States and the Southeast. They estimate, for example, that certain particularly intense Gulf Coast storms that occur, on average, only once every 20 years would occur in half that time under long-lasting El Niño conditions. In contrast, under long-lasting La Nina conditions, the same storms would occur on average only about once in 30 years. A related study was published this month in the American Meteorological Society's Journal of Climate.

El Niño events, which tend to climax during northern hemisphere winters, are a prime example of how the ocean and atmosphere combine to affect climate and weather, according to Schubert. During an El Niño, warm waters from the western Pacific move into the central and eastern equatorial Pacific, spurred by changes in the surface wind and in the ocean currents. The higher sea surface temperatures in the eastern equatorial Pacific increase rainfall there, which alters the positions of the jet streams in both the northern and southern hemispheres. That in turn affects weather in the U.S. and around the world.

Schubert cautions against directly linking a particular heavy storm event to El Niño with absolute certainty. "This study is really about the causes for the changes in probability that you’ll have stronger storms, not about the causes of individual storms," he said. For that matter, Schubert also discourages linking a particularly intense storm to global warming with complete certainty.

"Our study shows that when tropical ocean surface temperature data is factored in, our models now allow us to estimate the likelihood of intense winter storms much better than we can from the limited records of atmospheric observations alone, especially when studying the most intense weather events such as those associated with ENSO," said Schubert. "But, improved predictions of the probability of intense U.S. winter storms will first require that we produce more reliable ENSO forecasts."

NASA’s Global Modeling and Assimilation Office is, in fact, doing just that by developing both an improved coupled ocean-atmosphere-land model and comprehensive data, combining space-based and in situ measurements of the atmosphere, ocean and land, necessary to improve short term climate predictions.

Comments