The secret weapon against a colony of bacteria may be to stress it with its own protection system, which forces it to reduce its population through ... cannibalism.

Cannibalism among bacteria, explains Prof. Ben-Jacob from Tel Aviv University's School of Physics and Astronomy, is a strange cooperative behavior elicited under stress. In response to stressors such as starvation, heat shock and harmful chemicals, the bacteria reduce their population with a chemical that kills sister cells in the colony.

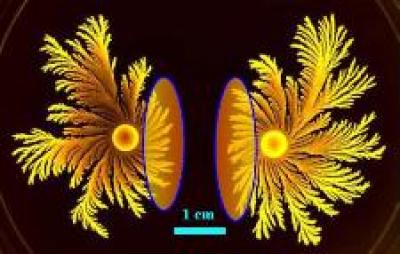

Competition between two sibling colonies of the Paenibacillus dendritiformis bacteria grown side by side. The cells in the marked regions near the gap between the two colonies are dead. Credit: AFTAU

"It works in much the same way that organisms reduce production of some of their cells when under starvation," says Ben-Jacob. "But what's most interesting among bacteria is that they appear to develop a rudimentary form of social intelligence, reflected in a sophisticated and delicate chemical dialogue conducted to guarantee that only a fraction of the cells are killed."

In the current study, the researchers investigated what happens when two sibling colonies of bacteria --Paenibacillus dendritiformis (a special strain of social bacteria discovered by Prof. Ben-Jacob) -- are grown side by side on a hard surface with limited nutrients. Surprisingly, the two colonies not only inhibited each other from growing into the territory between them but induced the death of those cells close to the border, researchers found.

Even more interesting to the scientists was the discovery that cell death stopped when they blocked the exchange of chemical messages between the two colonies. "It looks as if a message from one colony initiates population reduction in the cells across the gap. Each colony simultaneously turns away from the course that will bring both into confrontation," says Ben-Jacob.

"Our studies suggest this is a new way to fight off bacteria," says Prof. Eshel Ben-Jacob, an award-winning scientist from Tel Aviv University's School of Physics and Astronomy. "If we expose the entire colony to the very same chemical signals that the bacteria produce to fend off competition, they'll do the work for us and kill each other. This strategy seems very promising –– it's highly unlikely that the bacteria will develop resistance to a compound that they themselves produce."

In only a year, bacteria can develop resistance to a new drug that may have taken years and a small fortune to develop, but drug developers haven't utilized bacteria's cooperative behavior and social intelligence yet.

Bacteria, Prof. Ben-Jacob says, know how to glean information from the environment, talk with each other, distribute tasks and generate collective memory. He believes that bacterial social intelligence, conveyed through advanced chemical language, allows bacteria to turn their colonies into massive "brains" that process information, learning from past experience to solve unfamiliar problems and better cope with new challenges.

"If we want to survive the challenges posed by bacteria, we must first recognize that bacteria are not the simple, solitary creatures of limited capabilities they were long believed to be," concludes Prof. Ben-Jacob, who is now investigating practical applications for his current research findings.

The researchers' findings, published this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, were carried out in collaboration with a group from Texas University led by Prof. Harry Swinney and his post-doctoral fellow Dr. Avraham Be'er, formerly of Tel Aviv University. Prof. Ben-Jacob believes that the discoveries offer new hope for fighting both bacterial infections of today and the super-super-bugs of the future.

Comments