But back on viruses, because a number of virus types may possess a similar motor, including the virus that causes herpes, the results may also assist pharmaceutical companies developing methods to sabotage virus machinery.

The virus in the study, called T4, is not a common scourge of people, but its host is: the bacterium Escherichia coli (E. coli). Purdue researchers studied the virus structures, such as the motor, while the Catholic University researchers isolated the virus components and performed biochemical analyses.

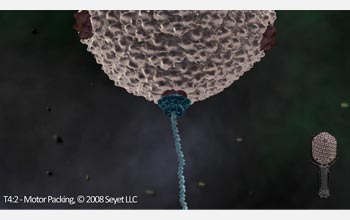

Image of DNA entering the gp17 motor complex on the T4 capsid. The image is a still from a video that can be found at: http://www.seyet.com/t4_academic.html. Credit: T4:2 - Motor Packing, © 2008 Seyet LLC

"T4 is what's called a 'tailed virus'," says Purdue biologist Michael Rossmann, one of the lead researchers for the study. "It is actually one of the most common types of organisms in the oceans of the world. There are many different, tailed, bacteria viruses--or phages--and all of these phages have such a motor for packaging their DNA, their genome, into their pre-formed heads."

The virus is well known to scientists. "T4 has rich history going back to 1940s when the original genetic tools to understand virus assembly were developed," adds biologist Venigalla Rao of Catholic University, also a lead researcher on the study. "T4 has been an important model system to tease out the details of basic mechanisms by which viruses assemble into infectious particles."

For the recent study, analyses involved two sophisticated instruments capable of studying structures at the nanometer (billionth of a meter) scale. One of the techniques, x-ray crystallography, showed the ordered arrays of atoms in the various structures, while another, called cryo-electron microscopy, let the researchers study the broader shape of the structures without the need for coating or drying out the specimens.

From prior research in 2004, the bacteriophage T4 is preparing to infect its host cell. The structure of bacteriophage T4 is derived from three-dimensional cryo-electron microscopy reconstructions of the baseplate, tail sheath and head capsid, as well as from crystallographic analyses of various phage components. The baseplate and tail proteins are shown in distinct colors.Credit: Purdue University and Seyet LLC

Having already determined the structures of a number of other viral components and how they self-assemble, in this study the researchers focused their attention on the small motor that some viruses use to package DNA into their "heads", protein shells also called capsids.

Not all viruses have a motor such as the one found in the T4 virus, but some viruses that cause human diseases posses molecular motors with similar functions, and likely have similar structures. T4 uses its motor to pack about 171,000 basepairs of genetic information to near-crystalline density within its 120 nanometer by 86 nanometer capsid.

The researchers found that the motor is located at the intersection of the capsid and the virus "tail" and is made of a circular array of proteins called gene product 17 (gp17). Five, two-part, gp17 proteins combine to form a pair of conjoined rings, arrayed so that their upper segments form an upper ring and their lower segments form a lower ring.

As a T4 virus assembles itself, the lower ring of the motor structure attaches to a strand of DNA, while the upper ring attaches to a capsid. The upper and lower rings have opposite charges, which allow the motor to contract and release, alternately tugging at the DNA like a ring of hands pulling on a rope.

The process draws the DNA strand upwards into the capsid where it is protected from damage, enabling the virus to survive and reproduce. After the DNA is inside the capsid, the motor falls off, and a virus tail attaches to the capsid.

Until now, researchers did not know how T4, or any other virus, accomplished the DNA packaging. According to Rao, "Since the assembly of herpes viruses closely resembles that of T4, this research might provide insights on how to manipulate herpes infections."

While many questions remain, adds Rossmann, the virus may lend itself to a variety for medical purposes. One example Rossmann cites is as a potential new weapon to fight dangerous microbes.

"Bacteriophages like T4 are a completely alternative way of dealing with unwanted bacteria. The virus can kill bacteria in its process of reproduction, so use of such viruses as antibiotics has been a long looked-for alternative to overcome the problems which we now have with antibiotics."

Comments